Part 2: How To Build Patient Communities

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

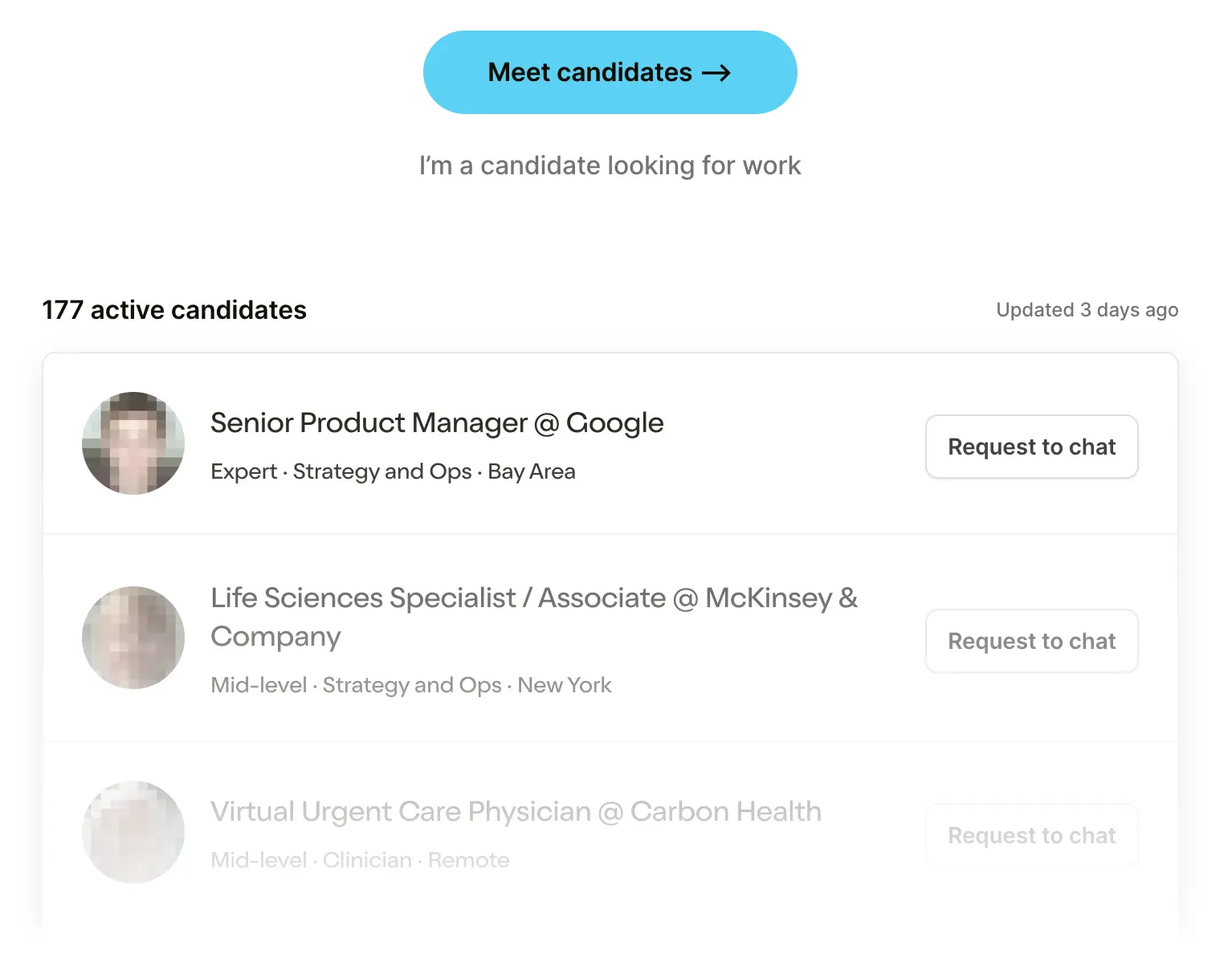

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveHealthcare Call Center 101

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Last week I focused on why patient communities need to shift from their current business model that’s focused on life sciences to actual behavior change that’s appealing to a broader universe of healthcare businesses. This week I wanted to talk about some features of patient communities that I think are important, and talk through two new investments I’ve made in this area.

If you’re starting a new patient community - your main competition is largely going to be Facebook, Reddit, and the community groups of disease-specific foundations (e.g. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation). Your job is to figure out how patients are not being served by these communities and fill that gap - competing head to head by offering the same exact product but on a different site is going to be a difficult sell. And no, offering a healthcare CPG product and saying you have a community when it’s really just a messaging board that becomes customer service and FAQs does not count.

Let’s talk about some of the core aspects of patient communities.

What is the problem you’re solving for patients?

Before getting into features, you should have a very distinct understanding of the kind of patient you’re looking for, the problem you’d like this community to solve for them, and what point in their care journey you expect them to find your community.

- A patient that’s been recently diagnosed with a disease that completely turns their world upside down is trying to learn what they can expect beyond the medical advice

- Someone that is pre-diabetic is advised to start making lifestyle changes and they’re looking for lifestyle tips from people culturally similar to them who have made incremental changes

- Someone with a nagging throat issue that doctors have not been able to diagnose tries finding others that may have had this issue so they can go to their next physician visit more prepared with some possibilities but the issue will likely resolve itself

- Someone that has cut themselves on a bagel they toasted too much that has suspiciously sharp edges (this may or may not have happened to me)

Each of these patient groups have different needs and pain points to be addressed. It could be questions they need answered, a sense of commonality with others, an empathetic explanation of how your lifestyle will change as your disease progresses, etc. All of the other features will flow out of these pain points.

Onboarding

Onboarding is by far the most important part of the community because it sets the tone of what a user’s experience is going to be like. It will also be very different depending on the intent with which a user joined. If someone is joining to contribute their data to research and get alerted about future clinical trials then you can have a much more intensive onboarding that asks them to fill out lots of questions to capture data. If someone is joining through a product they use, onboarding may look more like a walkthrough of the benefits they can get by using the product and a separate walkthrough on the community features. Or maybe the onboarding happens in-person in small clusters if your community has “cohorts” (e.g. weight-loss programs, AA, etc.) which allows users to bring their offline social networks into the patient community.

Onboarding will also be impacted based on the stage of the patient journey you expect most patients will be when they join. Is it post-diagnosis? Is it someone trying to self-diagnose? Is it someone that turns to patient communities when all else has failed? Thinking through this will help you figure out the best levers for distribution (e.g. if it’s immediately post-diagnosis get a physician to point them in your direction) and for on-boarding (e.g. if it’s self-diagnosing you probably want the least sign-up friction as possible).

Once onboarding is finished, the first screen someone arrives at will tell them what kinds of things people in the community post, how active the community is, what the community values, and what tools/information they have at their disposal as a part of the community.

Highlighting the strong parts of your community and making it as easy as possible for someone to shift from “lurker” to “contributor” is key. This could be pointing out questions in the community they’re particularly suited to answer, have them post something easy like an introduction, or even having other members of the group chat with new users as part of the onboarding (e.g. a buddy system). Feasibility here will depend on the clip of new users that join the community.

The onboarding for your patient community should make sense based on the use case the product is looking to fill and the motivations of the users, not a replica of some other patient community.

Identity and Private vs. Public

The role of identity is important considering how sensitive/private conversations are. Whether people use their names or remain anonymous will elicit very different behaviors on the platform. For example if you peruse disease-specific subreddits where people are anonymous, there are a lot of people asking questions about different symptoms they’re experiencing, medications they should be asking their doctor about, and people trying to figure out if they’re in the placebo arms of clinical trials by finding other people in the same trial (smh). If you go on public Facebook groups, the engagement skews way more towards “sanitized” information like lifestyle tips, memes about living with the disease, etc. If you go to private Facebook groups where you need to be referred in, the content is much more intimate. Identity and the public/private nature of the community should be aligned with the kind of posts you’d hope to have on your platform.

IMO one unexplored area is pseudo-anonymous patient communities, where people are verified by the platform and can choose to reveal themselves to individual users. For example, say a physician signs up to a patient community. The platform can verify whether the person is actually a physician - when they comment you know they’re a physician but they don’t have to reveal their actual identity. If patients DM or reach out to them individually, the physician has the option to reveal their direct identity. This gives users the ability to have some of the benefits of anonymity with some of the benefits of verification.

Moderators

Moderators play a very key role in any community, especially patient communities. As patient communities grow it becomes impossible to enforce norms and encourage behaviors without active moderation.

Moderators jobs are a few-fold:

- Post themselves and demonstrate what “good” community engagement looks like.

- Organize activities, surveys, AMAs, etc. to get the community to engage and contribute themselves.

- Discipline “bad” behavior - going about this is important because if bad behavior goes unabated it can quickly cause others to emulate that behavior or leave the platform completely. This is especially pertinent in healthcare communities where managing misinformation is very important - moderating this while being condescending will cause some users to go to sketchier sources for their information.

- Provide encouragement and positive reinforcement for people that do post, especially to people that are new or participate infrequently. This includes engaging people 1:1, disseminating rewards/points, and highlighting good member contributions to the rest of the community.

An open question is who should be moderator? This will vary from community to community - sometimes it might be a regular member that’s elevated to moderator thanks to their contributions, other times it might be someone’s dedicated job at a company to be moderator. Many patient communities have relied on nonprofits and patient advocacy groups to help with moderation, event organizing, and acting as a filter for advertisements/partnerships.

As I mentioned last week, physicians and other clinicians could treat their patient panels as opt-in communities and be the moderator themselves. Presumably, specialists have lots of patients with similar issues - connecting them together while moderating would make it easier for the doctor to disseminate information and probably make it more attractive for a patient with X disorder to see that doctor. Mayo Clinic Connect is an example of a provider getting involved in patient communities, but I’m thinking a bit more physician-specific.

General vs. Condition-Specific

Choosing whether to focus on one condition or create something usable for lots of different conditions will alter product decisions, business models, and distribution. For example - if you’re building a patient community around a disease with high pharma interest, then your business model will likely skew to some combination of real-world evidence products, patient panel surveys, and advertising with extremely high CPMs. You’ll also need a relatively thorough verification process that the patients actually have a given disease. If you’re building more towards a business model that’s paid on patient outcomes, it would make sense for your product to focus on the needs of people with that condition specifically: symptom tracking tools, integrations and partnerships with third-parties that would help that condition, community events, etc.

If you’re planning to go more generalist, consider what your core differentiation will be vs. Facebook, Reddit, and PatientsLikeMe. This could be business model (subscription, event revenue, etc.), community structure (multiple small communities instead of large ones), identity requirements, etc.

The willingness to share details about a disease will also change how you get new members, word of mouth referrals between patients, etc. For example - patients needing transplants will be extremely willing to share with anyone while patients with sexually transmitted diseases might not.

Group Size

As group sizes grow, they’ll naturally become less intimate as users know less people in the group. Dunbar’s number suggests we can maintain relationships with 150 people, but the reality is group dynamics morph way below that.

There are different dynamics between 10, 50, 100, and 1000+ people within a group. The smaller the group, the more likely people will feel attachment to the other members, social pressure to participate and meet group goals, and intimacy over time to share more personal details about their lives. The larger the group, the more likely someone will have an answer to a question and the group dynamic shifts more to broadcasting/marketing.

Group size will also lead to differences in communication style. Larger group sizes work better with forum style posting while smaller group sizes might make more sense to actually have a real-time chat that allows for more fun/casual posting. Larger group sizes will be more focused on infrequent, mass communication from the parent company vs. small groups might have daily messages from the parent company.

Group size is inevitably going to be a function of business model. If you make money through advertising or selling de-identified data, having a larger group with heterogenous data and personality types will make more sense. If you’re selling a product with a subscription, then you want people to feel like they’re getting value regularly and will be missing out on something if they leave.

Engagement

The key to any good community is whether when a person posts into it/contributes, there is some form of feedback from the rest of the community (likes, responses, shares, etc.). In healthcare one of the core reasons people seek patient communities is because they have questions about their disease that they feel they don’t have answers to. There’s probably a KPI here like (number of questions posed/number of those questions answered) that will tell you how likely those people are posting again in the future. Anecdotally from communities I run, if people ask 3 questions with no answer they’re way less likely to ask a question again.

A second form of engagement to be monitored is the types of contributions a person makes. If people are just advertising their services through a community, that will quickly degrade the experience. If people are only posting pictures but aren’t contributing at all to the surveys and other areas where you depend on monetization, then that’s a problem.

Creating some sort of prompts for engagement is important. This can be literal prompts which ask people questions to start discussions, or it can be prompts in the form of displayed data, photos, etc. This is one of the reasons I’m bullish on patient-tools-as-communities - a tool can be useful for the patient by itself (e.g. a wearable, food journal, etc.) but also a prompt for the community to chime in when they see the data. Strava has nailed this for example - where you can use it to track your bike rides and others can comment on it.

Finally, it’s important to recognize that engagement distribution will be uneven and you should lean on superusers of your platform who will key to keeping other members engaged as well. Here’s an interesting paper that looked at an online Asthma forums.

“People who wrote posts in the Asthma UK forum tended to write at an interval of 1-20 days and six months, while those in the BLF community wrote at an interval of two days. In both communities, most pairs of users could reach one another either directly or indirectly through other users. Those who wrote a disproportionally large number of posts (the superusers) represented 1% of the overall population of both Asthma UK and BLF communities and accounted for 32% and 49% of the posts, respectively. Sensitivity analysis showed that the removal of superusers would cause the communities to collapse. Thus, interactions were held together by very few superusers, who posted frequently and regularly, 65% of them at least every 1.7 days in the BLF community and 70% every 3.1 days in the Asthma UK community. Their posting activity indirectly facilitated tie formation between other users.”

Understanding the different types of engagement is key if you want people to actually open your application regularly vs. sporadically. Too many companies focus on scaling before focusing on quality of engagement which will quickly lead to people ignoring the platform and it’s very hard to restart high quality engagement once it drops.

Patient Influencers, Reputation Metrics, and Point Scoring

One defining feature of social networks is that certain people become influencers native to that platform. Think of all the people that have become internet celebrities by building followings on Youtube, Vine, Tik Tok, Twitch, etc. For example I’ve spent a lot of time trying to build a following on Twitter specifically because the platform values good analysis and thoughtful discussion.

Patient influencers are becoming a growing part of social media and how patients get information. These are usually patients with a certain disease documenting their life, things they do to manage their condition, descriptions of different medications or procedures and how it’s impacting them, etc. They’ll be some of the most frequent posters on a given community, but currently most of them focus on broad reach (Facebook, Twitter) or areas they have more control over their monetization (personal blogs).

If you’re building a patient community, you need to think about how people will be elevated on the platform and what they get as a result of their influence. What metrics should influencers on the platform optimize for that are aligned with your general business metrics? If they’re influential do they get some kind of money directly from the platform (a la Youtube)? Or do they get compensated from third-parties contracting with them (a la Instagram)?

You should think about ways regular users can build influence on your platform specifically vs. bringing existing patient influencers that already have followings on places like Instagram, Youtube, etc. The reality is people that already have influence on other platforms will very rarely completely shift over to yours.

I thought this interview with Alex Zhao who built Musical.ly and then Tik Tok summarized the phenomenon of new content creators well - you basically need to show users that they too can become influential if they dedicate time to your community because other users did it:

“In this new land, you have to build a centralized economy in the early days. This means that wealth distribution is accruing to a small percentage of people in your land. You make sure they successfully build an audience and wealth. This makes them role models for the country (and platform). You effectively create the American dream. People in Europe (Instagram) will start to realize that this "normal" person went to America (Musical.ly) and became super rich. Maybe I can do the same? This will lead to a lot of people migrating to your country (platform). However, you have to decentralize the economy at the same time. Having an American dream is good, but if it's only a dream — people will wake up eventually. You need to give the opportunity to the average person. You have to decentralize your traffic model. Give all users satisfaction in creating content and create a middle class.”

I should note that the patient influencer monetization and sponsored post side is still a very murky area from a monetary perspective. But the reality is that people will want to find ways to accrue social capital on your platform, so thinking through that aspect will be important either way.

Events

Good communities throw good events. I think people underestimate how much face time matters. Sure, you can be just the software layer for the community but if members start hosting events and they suck it’s going to reflect on the platform itself.

Events are not only good for bringing the community together, but they can be a great way to get members to sign up for new initiatives. It’s much easier to get members to enroll in registries, learn about trials, get excited about new product launches, etc. if you can explain it to them in person. Plus getting members to work together on projects like setting up an event for the community has a secondary effect of making those volunteers closer.

Foundations have done a great job with events (marches, talk series, galas, etc.) which are great for raising funds, involving people that aren’t just patients with the disease, and learn more about other things the foundation is doing.

Having a combination of large scale and small scale events are key. Your company doesn’t need to be the one that organizes all of them, but can be the enabler and offer support. Local chapters of a national organization decentralizes some authority to chapter leaders while providing support that’s contingent around the success of the event (to make sure the quality bar of the event stays high).

These in-person events can also be combined with online events which can be smaller but more frequent. For example hosting “ask me anythings” with physicians, talk series with researchers presenting their latest relevant paper in layman's terms, or semi-structured events with just other patients. Virtual events can be much more accessible to patients who don’t need to fly somewhere or travel (especially if they have a mobility impairing disease).

Don’t underestimate a good event.

My Investment in Most Days and Little Otter

Now that you know my thoughts on patient communities and how I think they’re going to evolve, I’d like to tell you about two investments I‘ve made in this area.

First, I’m excited to announce my investment in Most Days.

I’ve been looking for different “Strava for Healthcare” types of companies to invest in - aka. tools that are useful for someone individually but made more valuable through a social network built around that tool. I think these are excellent wedges into building new patient communities.

Most Days is a new social network for people improving their lives through daily changes. Most Days allows patients to set-up daily routines to manage their health for anyone struggling with any chronic health issue that requires some sort of daily regimen. Most Days attaches the daily routine tracking to micro social networks of other people that can provide support, accountability, and their own routines that you can borrow from.

Healthcare is starting to incorporate more Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO) tools into clinical trials, patient care, etc. These take the form of surveys, questionnaires, or scales you fill out. Frankly most of the existing PROs are designed terribly and actual usage by patients is super low. Instead of having standalone PROs, it might be more feasible to embed them into a company like Most Days that has more social elements. Check it out!

The second company I’m excited to announce an investment in is Little Otter, which provides online counseling to children and families to better understand childhood developmental milestones. The company gives parents on-demand access to parent specialists, therapists, and child psychiatrists. The service is currently in beta and will be launching later this year.

There’s a lot of interesting things happening behind the scenes to rebuild child psychiatry from the ground up to make it more tech native. But beyond the services itself I think there’s an opportunity to connect parents with similar concerns in a safe setting. Sometimes just hearing from others like you that aren’t in your immediate social circles is helpful in navigating your own journey with less judgment.

Their official launch is coming soon so I won’t give away too much, but if you’re interested you should check it out.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “please look at my portfolio companies I need to convince them I aDd ValUe”

Twitter: @nikillinit

P.S. If you wanna see the other places I’m interested in investing or are raising a pre-seed or seed stage round for your healthcare company, you can see other areas I’m interested in investing in.