Maternity Care and Payer Contracting with Marta Bralic Kerns

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

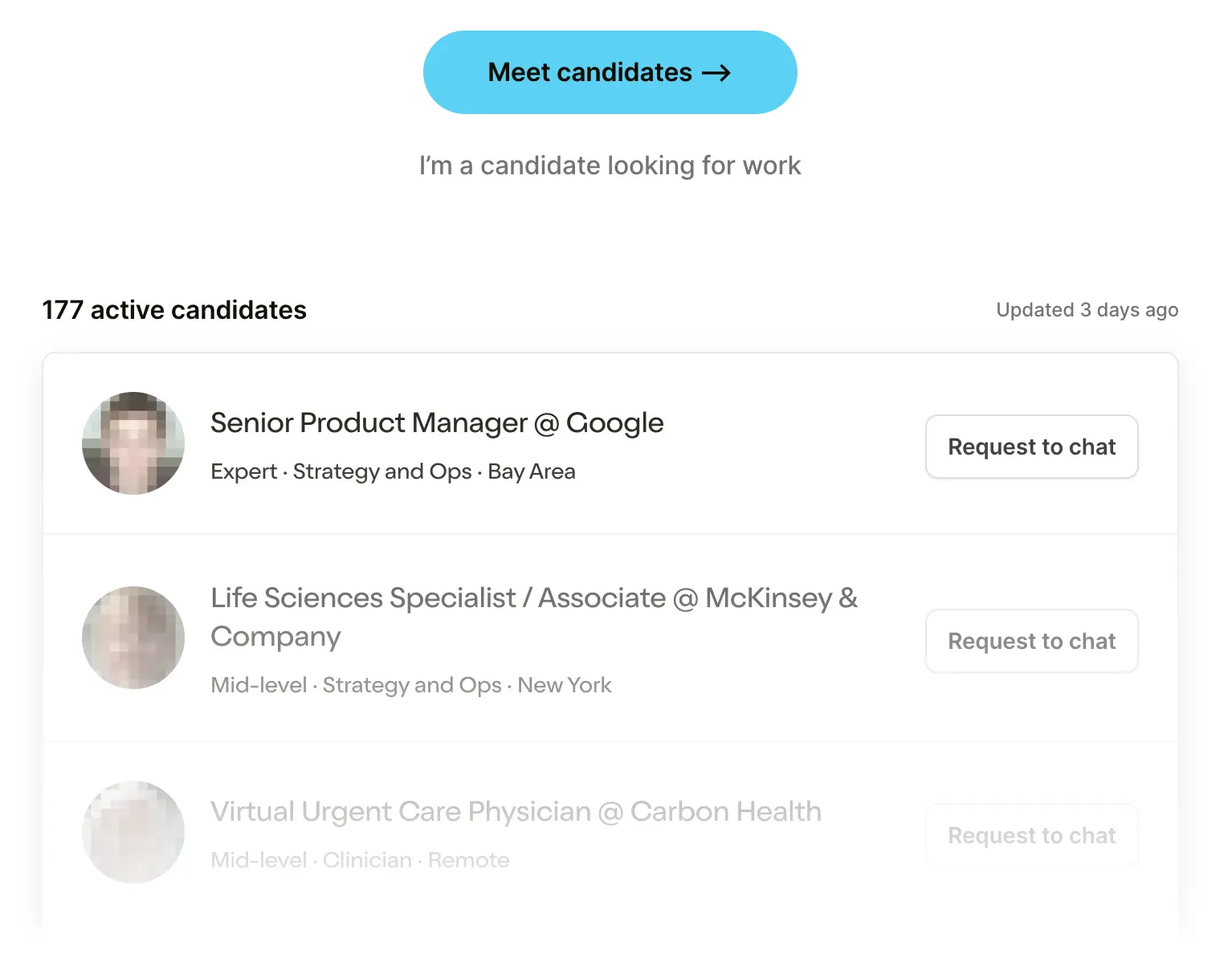

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveHealthcare Product 201

.gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Idk if people know this but I co-host a podcast on the side called Vital Signs with Jacob Effron and the team at Redpoint Ventures. I feel like I’m just too cute and bubbly to be contained by a newsletter. We’ve had some cool guests, like Mark Cuban, which was the first time in my life my non-healthcare friends have ever actually asked what I do.

I don’t want to inundate/repeat too much content so I rarely cross post, so you can subscribe to the podcast on Apple or Spotify if you’re looking for my nasally ass voice to whisper sweet healthcare nothings in your ear.

I’m making an exception today. Our last interview with Marta Bralic Kerns (MBK) was so dense with information and bangers that I want to make sure others see it + I had some memes in the chamber to add. Marta is the CEO of Pomelo Care, a virtual maternity care company and was previously doing special projects at Flatiron Health.

We talk about:

- the underlying drivers of maternal mortality

- what makes it difficult to transition to value-based care in maternity care

- how to land payer contracts

- and my favorite…how consultants can succeed in startups

In the full podcast you can also hear about how Marta interviewed me for a job and rejected me. And I’m definitely not still salty about it years later and definitely didn’t ask her to come on the podcast just to confront her about what was bad about the case study I presented.

This interview was summarized and ~*jazzed up*~ by me for entertainment value and readability.

Why is maternal mortality so much worse in the US vs. other developed countries?

MBK: The first reason is access to care. We just have way worse access to care before pregnancy, during pregnancy and in the postpartum period than our peer countries.

To give you a sense of that, the March of Dimes has done really good tracking on what we call maternal health deserts, which are areas where there is no OBGYN capacity or extremely limited OBGYN capacity, and over a third of US counties are maternal health deserts. So people are often traveling really far distances over an hour or two hours to get to OB care.

So you might ask, but how many people are actually living in those counties because by definition they might be less populous. One-in-eight births in the US today occur in a maternal health desert. There's a really significant gap in the amount of care that we're providing to people and the trend is moving in the wrong direction in that more and more OB practices are shuttering.

If you have fewer OBs, they're going to focus on the pregnancy. Then in the postpartum setting you're going to get very, very little capacity and patients aren't going to get the care they need. Meanwhile, more than half of the pregnancy related deaths in the US happen postpartum after hospital discharge.

The US also has a sicker population as a whole. When you look at the childbearing age population, we have much higher rates of comorbid conditions in the population than our peer countries. The most common things that affect pregnancy outcomes that we see higher rates of are diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, and behavioral health conditions including depression, anxiety, and substance use disorder.

These are the most common things that evidence shows us have a direct relationship to maternal and newborn outcomes. Every one of those things is related to preterm birth. Every one of those things is related to NICU stays and the US rates of these comorbid conditions are growing. So ~10% of births in the US are affected by hypertension, ~8% by diabetes, and the diabetes rate has gone up 30% in four years.

For many people, pregnancy is one of their first interactions with the healthcare system, and it's the first time they might even find out that they have diabetes or they have pre-diabetes or that their blood pressure is borderline and needs to be managed.

Are we just not training enough clinicians or is it too hard to get them into the areas of the country where a lot of pregnancies are? How do you think about the supply issue there?

MBK: It's both. Certainly OB as a specialty has not been a dominant attractor of folks for post general training, but then you also see this mismatch - you really do need OBs in every community. You need a Labor & Delivery unit pretty proximate to where people live - you do need really immediate access to the OB. We are seeing in some parts of the country where there's more family practice, the family practice docs and NPs are also providing OB care. But as you see more high risk pregnancies, you also need more high risk OBs and there's an especially low supply and folks aren't able to get to those high risk pregnancy docs.

Sidenote, there’s also a lot of differences in who actually delivers babies. In Europe, the majority of births are delivered by a midwife and in the US it's a very small minority.

Okay you’re finally allowed to talk about Pomelo Care - can you talk about the model and how it works?

MBK: We set out to solve these two problems, the access to care and the high risk comorbid conditions. The way we do it is we're a virtual medical practice. We employ our own providers and provide care for patients 24/7 during pregnancy and for one year postpartum. In that one year, we care for both the mom and the baby. We want to identify as early as possible who has any of these risk factors I was talking about before.

Routine care is good at identifying when a patient actually has preeclampsia and displaying symptoms that brought them to the doctor, but not as good at identifying who is likely to develop preeclampsia. But there are guidelines for what to do to prevent someone who has a high risk of developing preeclampsia from developing it. But because of the shortages and stuff we’ve already talked about, it just doesn’t happen as much as it should.

We’re a virtual practice focused on potentially higher risk pregnancies. We don't replace the OBGYN, we don't deliver the baby. We don't have brick and mortar practices. We are entirely virtual and our sole focus is using data. We use data to identify who is at risk for what as early as possible, as early a warning sign as possible. And then we engage patients in really personalized care plans and we hold their hand every single step of the way.

If we meet a patient before they've established in-person OB care, we make a warm referral to an OB practice in the patient's area. We send the chart, we give the OB context, and we also prepare the patient for this is why we recommended that OB (using data).

If we meet the patient after they already have an OB, we will coordinate care with that OB through their EHR. We don't believe in asking providers to use any additional software or any new workflows or have to send data manually or anything like that. We use the CCDA documents, we write notes through the EHR. So for example, if our registered dietician is working with a patient who has diabetes, they will send all their notes to the person's primary OB.

During the birth we also do virtual doula support + early labor triage, helping patient’s know when to go into the hospital. In those cases, we are sometimes calling the Labor & Delivery unit at the hospital to say, "Hey, this patient is coming. They're six centimeters dilated," or whatever it might be.

Most companies in the pregnancy space focus on commercial populations, but you all serve a lot of Medicaid patients. What makes building this business in Medicaid different?

MBK: We have some experience with employers and commercial plans and then Medicaid. We are held to such a higher standard in Medicaid and generally in the health plan world than we would be or we are in the employer world.

Employers spend a ton on healthcare for their employees, but they're not health plans. If you're a self-insured employer, you're being put in a position to manage the spend and manage the quality, but you don't really have the resources to do so. So you end up focused a lot as an employer on how happy are my employees? What's their experience? Are they getting value out of this? Are they coming back to work after having a baby, which is a big problem. What percent of women leave the workforce after having a baby?

They're very focused on these things that are critically important, don't get me wrong. I just don't think it's enough, I think that's table stakes. You have to have engagement, you have to have high patient satisfaction, you have to earn trust. But the Medicaid plans are asking “let me see all the quality measures, let me see the outcomes data”. And I think that just holds you to a much higher bar.

And then engagement wise, it is much harder to engage people in a Medicaid population. It's much harder to engage people through a payer relationship than it is through an employer. For employers, we send one email and we get half the eligible population to sign up that day. In Medicaid, 20% of phone numbers are not accurate or it's a disconnected number or it's not the person at all. So we also use different strategies to find the most up to date contact information for a person. We're working at the health plan to do that. We're working at the in-person OB to do that, just to find out if anyone has more recent contact information. We also send emails, we send text messages, we send mail to the house.

We knew we wanted to be in Medicaid because it's 42% of births, it's the higher risk births, it's where there's gaps in access, it's where there's more comorbidities, where there's more maternal morbidity mortality, where there's high racial disparities. We knew that is where the problem is and that is where we should go. So we almost made sure that we went there as early as possible so that we don't get complacent with the "easier employer model."

Part of the thing that's been surprising to me is that we haven't seen more payment model innovation here despite it being a relatively well-understood bundle. Do you have a sense of why or if there's anything changing on that side?

MBK: Yeah, it's two patients. That's the fundamental problem. It's the mom and the baby. And the vast majority of the avoidable spend is the baby. And it's been very difficult in our traditional episode context to create an episode that involves two patients.

So I'll give you a quick backstory here. My first job out of college as a business analyst at McKinsey, I was consulting for a state Medicaid agency in the south, and they were going to be one of the first recipients of these federal grants to do bundled payments. It was so innovative that we were moving from “you get paid differently for a vaginal delivery and a cesarean delivery” to “you're going to get one blended rate regardless”. That is a step in the right direction for value-based care, but it completely misses the biggest outcome of interest and the biggest avoidable cost, which is a NICU stay.

The average NICU stay is $76,000, but the average is skewed down by a lot of very short stays like ruling out bacterial infections and things like that that are one to three day stays, which is the most common NICU stay. So what you're thinking of is the preterm birth and those are half a million, million dollar stays. You have multimillion dollar babies as well. So these are extremely expensive cases. And all of our episode logic is focused on the difference between a vaginal delivery to cesarean delivery, which is like $5,000 nationally.

But it completely misses that every avoided NICU stay of which is 10%. 10% of babies in the US are admitted to a NICU. I was shocked by that. I thought it was like 1%, maybe 2%. What tipped me off to this problem was just my friends and family having babies in the NICU and I started wondering, well, how often does this actually happen? So I was 10% saw the average cost, just like something is not adding up here.

But the problem is no one thinks they can manage the NICU risk. You have this real gap in accountability where the OB is saying “Well, that's not my patient. I can't take risk on NICU costs. I'm not the one deciding what happens in the NICU?. And then the neonatologist is saying “well, I can't take risk on these babies because everything is decided upfront during the pregnancy and by the time they're admitted to the NICU, so much is predetermined”.

A lot of people reading this are probably all struggling to get payer contracts. We have to know how you got your first payer contract. It feels like it'd be a good story.

MBK: For me, it was the hardest part and the worst part of starting a company.

When you break it down by line of business, there's thousands, and so you really do have this huge opportunity, and I viewed it as a numbers game. The advice we got was to be really focused on your go-to-market. Pick one state, pick one line of business, pick one archetype of payer that you want to talk to and only talk to them. But then your numbers are really small, especially if you’re thinking about this like a sales funnel.

So we actually took the opposite advice. We got feedback that our go-to-market was frenetic or unfocused or whatever it is, but we would talk to anybody who was willing to talk to us. I was doing nine sales calls a week from the beginning of the company, just anyone who had talked about, so how do you get those intros, investors, advisors, finding people who used to work at health plans and bringing them on as advisors to introduce you, friends.

We also spent time talking to organizations we don’t directly sell to because they could introduce us to payers. We spent a ton of time talking to health systems. And people would say, well, why are you meeting with health systems? You're not trying to sell them anything. But we got intros to 30 payers from the health systems. Because they're like, well, we want this to exist in the world because it would be helpful to us.

The more pitches we did a week, the better our pitch got. We got feedback from those pitches. We really quickly iterated on it. We got better at it.

The second thing that everyone told me, you need to find a champion. It's so hard for an internal person at the payer to push one of these new innovations through that you need someone who really is passionate so that they will go through the bureaucracy and the steps and spend six months trying to convince everyone else that can say no at the payer.

Once you get that from that conversation of this is what I've been looking for, it still took us nine months to get a contract. From those conversations where someone says “oh my God, thank God you're here. This is what I want”. It takes us three months. We made this short by figuring out how we were going to price and how we were going to contract. Because again, these health plans are so difficult to navigate even for the people within them. So we need to tell them, this is exactly how our process works.

The next step is to bring in your network team. This is the type of contract template. Do you have one of those? Can you send it to us? Just very clear steps so that for your champion, it is very easy for them to move forward. And we spent all this time trying to ask other companies, well, how do you contract? And we got contract templates from other companies.

[NK note: We have a course coming out soon that’s all about this, called How To Contract With Payers :)]

So I'd say as you're pitching, also try to figure out how am I going to contract? Am I going to be a provider? Am I going to be a vendor? How am I going to price? How am I going to justify that price? And who does my champion need to bring into the next meeting? If we can solve all that for them, then you can set up the next meeting in two weeks because there's no thinking to do.

One question from your Flatiron days. Flatiron bought an EMR and it somehow worked. And then no one really did that strategy again afterward. I would love to hear the thought process of buying an EMR and why you don't think more people try it out.

MBK: Well first of all, I would never wish an EHR upon anybody. It's an extremely difficult product to build and to maintain. Most EHR users absolutely despise their EHR. I think it is one of the lowest NPS scores of any technology available. And so it's a real burden to own an EHR.

Flatiron had this vision that we're going to have the largest real world data set in oncology and we're going to help pharma do research more quickly, academic use it, FDA will love it, etc. It’s an amazing vision but it's really hard to go one-by-one to different cancer clinics and do some kind of exchange of value for the data.

In the case of Flatiron we acquired a company that was ahead of its time as a cloud-based EHR, before cloud-based EHRs were a thing. And somehow miraculously they had negotiated with oncology practices to have rights to the data (of course de-identified to be used for research). And they had a huge market share in oncology, plus they were a small-ish family owned business that could be acquired.

To find those three factors lined up plus it was existential to Flatiron's vision made it a slam dunk. For most companies, they don't have that slam dunk. They say it'll improve workflows or it'll improve point of care quality metrics. For Flatiron it is very clear. If we buy the EHR, we will have the largest source of rural oncology data. We'll have rights to use it for research and we will build the business we always dreamed of. But I think if you don't have that direct path, it probably doesn't make sense.

Bonus question: You transitioned from McKinsey to startups and just absolutely crushed (according to your coworkers). Any advice you have for people making the consulting -> startup transition.

MBK: I think it's way more important to focus on finding a high growth company and an amazing team than focusing on the role. Because everything else will basically change. Whatever role you take first is going to change within six months. Whatever business plan the company has, especially if it's at an early stage, is probably going to change within six months. So I would anchor on “is this company growing really quickly?” Because that is the number one thing that creates opportunity for you because there's always more work than people to do it.

That was very much my experience at Flatiron. I felt embarrassed in my title for the longest time because everyone would be like, “what's special projects? So do you not do the unspecial projects? Are you too good for the unspecial projects?” I hated the title, but I was constantly raising my hand saying, I'll do that, I'll do that, I'll do that.

That's how you earn the credibility. I made it my business to figure out what they were worried about, what was keeping them up at night, what were they stressed about? What unsolved problems did they have? And to try to solve it for them without them even asking.

Relatedly, one of the best framings I've had for this is “It's not your job to solve the problem, it's your job to get the problem solved.” Basically if I was going to raise my hand, that didn't mean I had to go alone in a room and find out the answer by myself. I could pull in experts, I could pull in other people. But I was the one accountable for everything to get done in that time frame. There’s a distinction between doing it and being accountable for doing it.

The last thing I would say is just move really fast and know all your details. Know the ins and outs of everything you're doing, know all your numbers, and just move really quickly through everything you're doing.

Also no one's going to have strategy in their title. At Pomelo, no one does “strategy” here, we execute. We do execution. We just put execution in everyone's title.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. "Executionboi" actually that sounds really dark

Twitter: @nikillinit

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

{{sub-form}}

--

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.