The weird CPT code process you need to understand

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

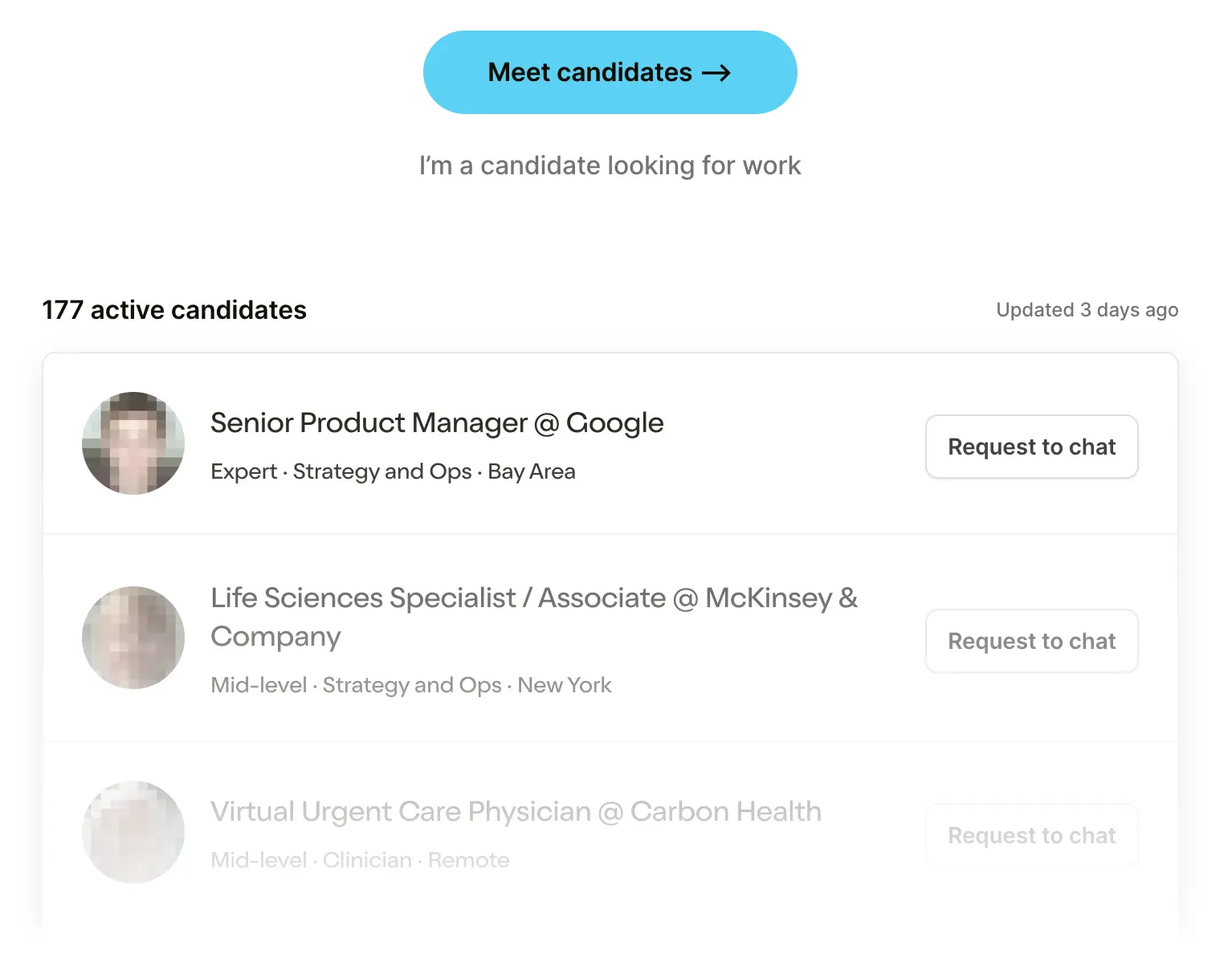

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveHealthcare Product 201

.gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

CPT - The Language of Healthcare Services

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes dictate what gets reimbursed in healthcare. If you don’t know what these are, you’ve lived a beautiful life outside of healthcare and you can still choose to turn around now.

Most people outside of healthcare don’t understand what CPT codes are. Most people inside of healthcare don’t understand why CPT codes are. Today I’d like to try and explain both parts of that contrived sentence, and also how CPT codes are holding us back.

[CPT codes are also known as HCPCS Level 1, but that level of specificity isn’t really needed. Just know they’re the same if it comes up, but if someone is saying HCPCS to you in real life you should probably run the other way.]

What are CPT codes?

When you go to see a doctor, they need to submit a bill to get reimbursed for their services. CPT codes are a way to codify the doctor’s services in a uniform way so that the payer/health insurance companies/hospitals know what services you did and what to pay for them. We talked about the basics of this process in the revenue cycle management post.

Here are some examples for “online digital visits”, which seems like a redundant phrase but whatever I’m not the name police. Many of the CPT codes will be different depending on whether or not the patient is new, how much time was spent with the patient, if you want to commit fraud, etc. There are more than 10,000 different CPT codes.

There are also CPT code modifiers, which are used to add additional relevant information about the service. For example, you’d add the modifier “22” to the end of a CPT code if the surgery actually became more difficult than you thought (maybe due to excessive bleeding or you left your watch in there and need to run it back). The modifiers give more context about the service that was rendered and whether the payer should pay more or less.

Just to make things even more fun, the CPT codes are grouped into three categories.

- Category I - These are the bulk of CPT codes utilized, and are basically for any services that are widely accepted in medicine and have evidence backing them up. These codes are split into six sections: evaluation and management, anesthesiology, surgery, radiology, pathology and laboratory, and medicine.

- Category II - These are not codes used to reimburse for services, and instead track performance and quality measures like lab values. For example, code 2023F is “didn’t find diabetic retinopathy”.

- Category III - These are temporary CPT codes used for more experimental stuff and emerging technology. For example, code 0791T is an add-on to use virtual reality for gait rehabilitation. These codes last five years, and then either get scrapped or become Category I codes. These rarely get reimbursed and are generally used to track how the new technology is being used, mostly to make a case for a Category I code later. It’s great for people that like to document and not get paid for it.

If something does not have a CPT code, it does not get paid for by Medicare and you’re fighting an uphill battle with private payers. One of the things that new digital health and device companies struggle with is the fact that no CPT code exists for them to get reimbursed. Hospitals/physicians are way less likely to purchase or distribute your product if there isn’t a way to bill using your tech/device. This leads many companies to:

- Go to employers or payers directly to get paid per member per month or via some specific outcomes-based metric instead of CPT codes on an encounter basis.

- Try janky ways of using existing or “catch all” CPT codes, which typically don’t reimburse enough for what you’re trying to do. For example, code 99091 was a catch all code for collecting/interpreting digital data that remote monitoring companies would use until new, more specific ones came out that reimbursed more. Some companies can get into hot water if they start using a code that really wasn’t meant for them.

- Start the long process of getting new CPT codes made for their product. HeartFlow, for example, got a set of category III CPT codes like 0501T made that fit pretty specifically to its technology that diagnoses coronary artery disease (CAD) by looking at how your blood flows.

Why do we need CPT codes and who governs them?

Now let’s get to the fun part of this. How did CPT codes actually come to be?

A little history lesson is needed here. Imagine it’s 1965. Medicare is created, the number of people enrolled in different private health insurance plans has skyrocketed for the last few decades, and computers are starting to enter hospitals.

At this point it becomes clear that physicians need some sort of ontology to describe the things they’re doing so they can send bills to insurance companies and analyze data about how they’re performing. In 1966, the American Medical Association (AMA) creates the first edition of the Current Procedural Terminology to do this, mainly targeting surgery. In the years after, it expands to many more procedures, screenings, therapeutics, and more.

But the real doozy happens in the 1980s: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) makes it mandatory for everyone to use CPT codes to get reimbursed by Medicare. Soon after, it does the same for Medicaid. In 1996, HIPAA is passed, which sets rules on which standards are to be used to exchange information electronically. You can guess which standard made the cut.

To this day, the AMA continues to run the process for maintaining and adding CPT codes, which they hold the copyright to, while enjoying a government-mandated monopoly. For that pleasure, they charge anyone that uses CPT codes a royalty, yielding a business with financials that would make a SaaS investor climax. They even recently seem to have moved from charging per organization to per user in the last few years. Based on some outpatient EMR websites, now it costs ~$17.50 per user per year for every organization that uses CPT codes. Which is, by law, literally everyone in healthcare.

Well at least if we’re paying that, then there must be a high quality process for deciding CPT codes right?

The process for getting a new CPT code

Oh boy, I need to take a deep breath for this one.

There’s a multistep process to get a new CPT code and figure out how much it should be reimbursed. Let’s use an example.

Step 1: Say I want to create a new code “CPT 42069 - checking for hernias literally any other way.” In most cases like this, I would first go to the relevant specialty society like the American Academy of Family Physicians and get clarification on whether or not this would already fall under some other CPT code. If not, then I would ask the society or an individual physician or even a payer to advocate and apply for a new code on my behalf.

At this point, you have to demonstrate to staff members of the AMA and subsequently an Advisory Committee they’ve appointed that the service you’re providing could not fit into any existing CPT code. This can include writing a justification for the relevant codes and why they’re not relevant.

You’d also include the relevant papers that support this service, a description of the type of patient that would typically get this, what care setting it happens in, how frequently, etc.

Step 2: The staff and Advisory Committee agree that CPT 42069 is novel. Now I have to create a presentation to justify it and present it to the CPT Editorial Board [ominous DUN DUN DUN is played]. This board meets only three times a year to review a lot of CPT changes, applications, and some other things. This committee consists of 17 people, a mix of representatives from the specialist societies, payer representatives, etc. All of them are MDs or DOs currently.

At this point the committee can choose to approve, postpone, or deny the decision.

Step 3: So now CPT code 42069 exists, but how much should it get reimbursed for?

To figure this out, there is another shadowy committee governed by the AMA called the RUC (RVS Update Committee which is an ACRONYM WITHIN AN ACRONYM AHHHHH!H!H!H!H!). This committee is formed of 32 members, most of which are appointed from the different specialty societies like the American Academy of Neurology.

Ignore the alphabet soup, the important thing is this committee is tasked with gathering data to make a recommendation on how much they think Medicare should pay for this CPT code by figuring out the “relative value” of each service. To do this, they design a survey to send to a random sampling of physicians that attempts to answer the following questions.

- How much work does the physician take to do this service? This is calculated based on the time taken to do it, the mental effort/judgment necessary, the expertise required to do it, and the psychological stress if something goes wrong.

- What are the direct expenses a practice incurs to do this service? This includes non-physician clinical staff time, medical supplies, and medical equipment used.

- What is the professional liability of this service? In other words, what are the malpractice risks and chances here?

- Do you love this shit? Are you high right now? Do you ever get nervous?

This survey gives a reference clinical vignette that the doc filling out would be used to seeing, and then a new clinical vignette that’s closer to whatever CPT 42069 would be used for. The doc would then fill out information around how much time it would take to do them, how complex it is, etc. Here’s an example I found online for what the survey looks like, and here are the AMA slides for how the RUC process is run.

Step 4: Using the data from the surveys, the RUC committee then debates this live. If they can agree, they make a recommendation to the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) on how much they think Medicare should reimburse that CPT code. Interestingly, in the past, CMS used to agree with 90%+ of these recommendations, but in the last 10 years that’s dropped to 75-85% (source: AMA page 12).

Most other insurance companies end up using the Medicare amount as a starting point to figure out how much they should reimburse too, so this number matters a lot!

Step 5: CPT 42069 goes live on Jan 1 of the next year. It’s an absolute hit, 90% of healthcare spend is now exclusively due to this code. When codes like this suddenly become popular, the RUC then re-evaluates the code and determines whether or not it should be paid the same amount or adjusted higher/lower.

All in all, this process takes about 1-3 years, depending on how many revisions each committee needs to come to a decision. Most companies I’ve talked to assume at least two.

The issues with the CPT process

The basics of this process were created in the 1960s, largely as a response to Medicare. We needed standard ways to bill and we needed a party that represented physicians that would act as a counterbalance to the government unilaterally declaring the prices they’d pay.

But it’s been nearly 60 years and not a ton has changed about this process - in fact, I think it needs a serious overhaul. Some of the main issues:

Government-mandated standards - Look, I get the intention behind why the government has mandated CPT codes as the standard in healthcare. If a standard is NOT mandated, you get all the current problems like interoperability, prior authorization, etc. where every org creates their own standard and subsequently a ton of administrative work is required to deal with different processes, harmonize data, etc. If the government mandates the standard, then you don’t run into that problem.

The problem arises when the standard is both MANDATED and OWNED/COPYRIGHTED by an organization. That creates an unfair monopoly and a process controlled by a single entity vs. an open-sourced process people can see, understand, and contribute to themselves.

It feels like this shouldn’t be owned by an interest group and it should be open-sourced.

It’s just really slow - It’s no secret healthcare moves slow. I’ve seen Darwinian evolution happen quicker.

In this case, the slowness can kill innovation for really trivial reasons. Companies will gravitate towards building incremental services/products that can bill existing CPT codes vs. needing to wait multiple years for something totally novel.

There’s a very serious first mover disadvantage here, and in many cases investors won’t want to fund companies and underwrite the risk that they won’t figure out how to bill for services. We want investors to underwrite more technological and care model risk, not “whether or not we know how to format a receipt for these services” risk. We’re watching this unfold in the digital therapeutics space now, with many companies shutting down or pivoting because they couldn’t figure out the payment mechanism for years.

Trying to keep your company alive for 2+ years while you wait for a committee to convene to decide your fate? I’d pray for the sweet release of death.

The open but not really open nature of it - I mean the codes are behind a paywall, for starters. On top of that you have to buy the book for details about those codes. I know healthcare is behind on software, but has no one heard of torrenting?

Beyond that, you can attend meetings but they don’t tell you where they are, they put all sorts of weird barriers when you do, and you have to sign NDAs. From this report:

“For example, at the RUC’s January 2016 meeting in Miami, which an author of this report attended, organizers claimed there was limited room available for the public, even though the meeting was held in an enormous ballroom with plenty of empty spaces. All attendees were also required to sign sweeping confidentiality agreements.”

What is this, E11even? How is a Miami meeting of doctors harder to get into than the Miami club?

Or, for example, you can see the minutes and votes for the RUC meetings, but it doesn’t really show the actual discussion, survey data, power dynamics, if the catering was dank, or how people voted. They only show the end results. For the CPT Editorial meeting, you can basically only see the agenda and results, not what happened during the meeting.

For something with so much influence, it feels like this should be C-SPAN’d, to be honest.

A small, non-representative group making decisions - It’s kind of insane to think that such small groups of people have so much influence in deciding whether a service can be reimbursed and for how much. So it matters a lot who those people are, and that’s the core of a lot of issues IMO.

On top of that, CMS reimbursements have to hit a budget neutrality by the end. This means that suggested increases for some CPT codes are going to come at the expense of others. This inevitably is going to create a gladiator pit of doctors trying to protect their own fiefdoms with an orthopedist Russell Crowe asking if we’re entertained.

Which matters because these committees are disproportionately represented by specialty groups. The RUC committee, for example, is a one person, one vote system. But only four of the 31 seats go to primary care, despite about 1/3rd of physicians being primary care doctors. A general criticism is that this tends to yield more weight towards procedure-heavy CPT codes that specialists tend to do vs. cognitive ones. The thinkboi/thinkgals of the doctor world don’t get the value they deserve!!

Plus, most representatives on these panels are from large hospitals and academic medical centers. This usually means advocating for higher reimbursements in hospital settings, or making recommendations about where different services should be allowed to be performed. You can imagine how hard the hospitals fight to keep the services within the hospital setting.

The fucking surveys - I find the use of surveys in this process to be horrifying. They’re so important that if you google them, you see these Uncle Sam style recruitment posters the different specialty societies put out to make sure they physicians actually do them.

Despite all that, the response rate is shit. In 2015, the GAO found that the median number of responses to surveys for payment year 2015 was 52! The median response rate was only 2.2%! 23 of the 231 surveys had under 30 respondents! That’s a “Nikhil on the dating apps” level response rate.

Second, the patient vignettes frequently aren’t actually reflective of the real-world but are actually a concocted scenario. For example, here’s an article that talks about how the vignette given for a skin substitute was based on a patient with severe burns and required four hospital visits. In the real world, that skin substitute was used for ulcers and not burns, which happened in much cheaper outpatient settings.

“Some podiatrists suggest 25 minutes is longer than the procedure typically takes, though this can vary. Lee Rogers, associate medical director of the amputation-prevention center at Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Los Angeles, says he requires seven minutes on average.

"I can't believe that's the vignette they based this code off of," he says.”

In fairness, the RUC committee also revalues CPT codes (frequently downward), especially if their usage starts increasing or expanding to other areas. But only <4% of CPT codes seem to get reassessed annually, so a lot of them can stay the same for a long time, especially if their utilization doesn’t change much.

Finally, physicians who do the survey are obviously incentivized to say these procedures take an extremely long time (since it results in how they get paid). There are several different studies (here, here, and here) that all show pretty large discrepancies in how much the physicians report something takes in minutes on the surveys vs how long it actually takes based on real-world data. Of course!

We have so much data today to track more granularly how long these things take. In those studies above the survey numbers were inflated compared against the actual operating room times to make their point. Why didn’t they just use those in the first place? They reflect the real-world and it’s a much larger sample size. With telemedicine consults being tracked, all hospitals monitoring the usage of every room, etc. it feels like we can use better and more objective data sources.

Payment around effort instead of outcomes - The underlying ideology around CPT codes and how they’re valued is, “how much work is it to do this”. It’s a measurement of the inputs, which inherently is anti-efficiency. For example, the most used CPT codes both have minimum time requirements. And in the RUC surveys, a very key input is work time for a given service and how complex the task is.

Increased reimbursement for time and complexity naturally disincentivizes efficiency. I think there’s a reason why a lot of the chatbot or asynchronous telemedicine companies gained traction first in the cash pay market. Nowadays, thanks to the AMA’s CPT changes in 2020, providers can bill when you message them in MyChart. And they’re taking advantage of that.

It’s clear that AI is going to make a lot of workflows more efficient and might even potentially fully automate certain interactions soon. If we have a billing and reimbursement system that increases reimbursement based on time spent and complexity, no one will adopt these tools.

We should aim to move beyond CPT codes and figure out more novel contracting structures between patients, payers, and providers. We should pay for the intended outcome instead of the inputs to that outcome. I’m interested to see if companies that enable new types of contracting like Turquoise, Accorded, Mishe, etc. are able to move us beyond the CPT rails and instead to something more flexible.

Conclusion and parting thoughts

Like everything in healthcare, CPT codes were born from a well-intentioned place. We needed standards when talking about services. We needed physician input for reimbursement. We needed the government to coordinate everyone and mandates were one of the tools available.

But it’s clear that this process has become warped and distorted over time. The process is opaque, has turned the people and organizations involved into gatekeepers, and is not reflective of the real-world needs.

A friend of mine actually attended a CPT editorial meeting by accident and gave me a short summary I thought was amusing but also depressing:

“First, in classic healthcare fashion, the infrastructure for the event was wildly outdated. There were two projector screens used, one being a screenshare of a Word doc with the proposed code change that they were highlighting and typing on live (not commenting / track changes, and in front of an audience of hundreds). In addition, some affiliated group proposing the change was dialed in but kept getting disconnected (or maybe muted?)....

In the end, the person who was struggling with being dialed in tried to talk, but someone on the panel decided they were done with the discussion, motioned to end the discussion, and quickly got a second to close it. The panel just wanted to move on at that point after hearing back and forths from the audience for a CPT that was only approved in October 2019 and went into effect January 1, 2020, less than two months before this panel.

Broadly, the way the AMA handled the small portion of the overall panel that I witnessed was concerning: insufficient technology to support information sharing and discussion, dismissal of the topic and cutting off the stakeholders, and revisiting a Category III just a few weeks after it went live. “

Yeah this feels like an apt metaphor for healthcare as a whole.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “Knuck if you RUC”

Twitter: @nikillinit

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

Thanks to Brian Dolan and Joe Connolly for reading drafts of this

P.S. Claims course closes signups this week, and we're getting together an initial alpha group for our Onboarding Clinicians to Tech Course (email ellen@outofpocket.health for details).

---

Featured Jobs

Sign up for the featured tier in the Talent Collective to get your jobs in the newsletter, on Twitter, etc.

- Ursa Health is a data analytics software company that is reinventing how organizations use data to learn, make decisions, and innovate in healthcare. They're hiring a Healthcare Data Integration Engineer.

- triValence is reimagining the B2B healthcare payments and supply chain ecosystem. They're hiring an Outside Sales Executive.

- Mantra Health is the leading provider of digital mental health care solutions for colleges and universities. They're hiring a Strategic Finance Manager.

- Develop Health is building a copilot for medication prior authorization using AI. They're hiring a founding LLM engineer.

{{sub-form}}

---

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.