All of the main problems with US healthcare

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

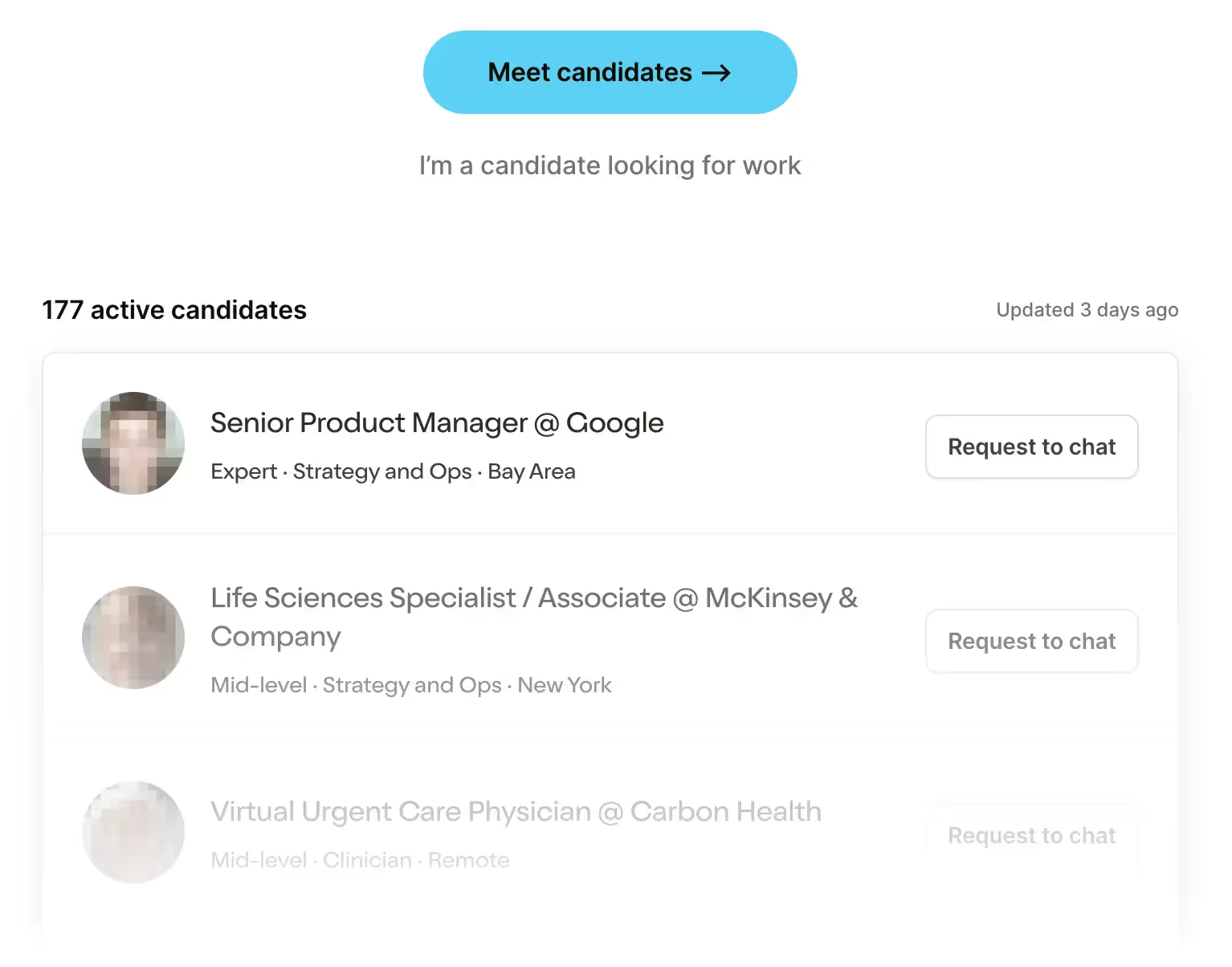

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveFeatured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Someone asked me the other day what I thought the main issues in US healthcare are. F*** you dude, why do you wanna ruin my day? I hadn’t even sat down for coffee yet, so I hit ‘em with the *chuckle* “where to begin” and proceeded to evade giving a specific answer. It was like 9 AM and I’m not trying to have any substantive conversation until at least post-lunch.

But then when I got home, I realized that it’s a reasonable question, and it might be worth trying to nail down some specifics. So I did my best and thought I’d share a list of the things I think are core issues - some ideological and some tactical. There are lots of problems not mentioned that I think are downstream effects of one of these.

Obviously this is not going to be exhaustive - there are a billion things wrong with our health system. I’m going to try and hit the main ones, but feel free to respond with key ones you think I missed.

Volume-Based Business Models + Healthcare Consumption

Virtually every business model in healthcare today is volume-driven in some capacity. Fee-for-service, # of drugs sold, etc. So many issues in healthcare can be tied to a downstream effect of the incentive misalignment that happens when you’re incentivized to “do more healthcare”.

But there’s an ideological question that we seem to be uncomfortable asking directly in the US: should people be able to consume as much healthcare as they want and wherever they want to get it?

This ends up becoming a war of the core American belief that we should be able to have as much choice as we want with the somewhat practical truth that unlimited flexibility and consumption come with a cost. That cost is FREEDOM!!!!! U-S-A, U-S-A.

I’m not an economist so I don’t have the tools to really poke at this post, but it makes a pretty convincing case that when you normalize for Gross Domestic Product and compare prices relative to income then most of the issues in US healthcare are actually a result of consuming more healthcare services.

This is why the history of healthcare seems to be shifting to or away from Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) style plans that control consumption to some degree. Yes, if you have to see a primary care physician before you do anything + have tighter controls on the drugs/scans/procedures, you can control costs. But then people get denied care, sometimes care they really need. Or they’re denied the doctor they want to see. Or they have to tell the primary care physician that they’re not sexually active for the 100th time.

Just look at this chart of the kinds of plans covering patients over time. Conventional (also known as fixed indemnity) gives you a lump sum cash to go wherever you want. That’s followed by the growth of HMOs, which are more restrictive. Which is then followed by PPOs, which give more flexibility. Except…is that a small resurgence of HMOs I see through 2019? And now everyone just threw their hands in the air and put the onus on patients through deductibles. Get me off this rollercoaster.

Other countries also have some form of fee for service but set controls on consumption and prices. This tends to manifest as some form of rationing - longer wait times for certain things, lack of access to cutting-edge drugs, etc.

However, in the US, we don’t really put our foot down. Instead, we implement half-ass things to stop consumption like copays/coinsurance but then also want to make sure people get to keep their own doctor, get access to every drug, etc. And on top of that everyone expects access to the “highest quality care”, even though that’s simply not possible when the number of people the best doctors can see is fixed. We’ve been trying to move to value-based care models, but practically, this is extremely hard to actually implement, for many many reasons that I’ve outlined here.

Government vs. Market Forces

Related to the above - the US isn’t sure if it wants the government to make decisions or free market competition to adapt to consumer interests. Currently, it’s the worst of both worlds. It’s regulated enough to make it difficult for new and small businesses to compete, while also free market enough to gouge the vulnerable.

The government could be the biggest negotiator in healthcare, but instead has offloaded that job to private companies or created weird carve outs like Medicare not being able to negotiate drug prices. In other countries, the government sets prices from the top down through regulation, setting the universal rates that hospitals/health insurers can charge, capping the amount of budget increases that can occur, or actually running the hospitals themselves. The US tries this in some ways like Maryland’s all-payer model where every payer in the state pays the same rates for hospital services, or the Veterans Administration that’s funded and operated by the government. But it’s not consistent nor at scale.

Instead, the government could help spur competition in the private market to bring prices down. But today you have weird things like Certificate-Of-Need laws that prevent new facilities from being built, increased reporting/regulatory requirements to be compliant, or quality related bonuses that increase overhead costs for small businesses. And the fact that these rules are different for every state makes it very very difficult for any company to scale nationally.

There are ways that the government can also be a player in stimulating private market competition. For example, Singapore has something called Medisave, which provides tax-exempt, interest-bearing accounts for out-of-pocket healthcare expenses. They’re also mandatory, so you/your employer has to allocate ~8-11% depending on your age. This forces healthcare companies and private health plans to compete for those dollars you saved. Or, other countries guarantee some form of public option for coverage or care to cover the necessities (probably with waits and no frills), which forces private sector companies to compete to be better than the public options.

I think one issue core to this is that Americans really really don’t want the government to tell them what to do and don’t trust the government to make optimal decisions on behalf of its citizens, sadly. People hated the individual mandate (which forced you to buy health insurance) so much that Trump essentially removed it. There was that whole snafu with “death panels” that became portrayed as “the government chooses if you’re worthy of medical care”. In the US, if you told people they had to allocate 10% of their income to healthcare every year, people would lose their goddamn minds. Even though now we basically end up paying 18% passively, it was my choice to do so, and you can’t take that away from me.

There Are Too Many Healthcare Systems

The US is not a single healthcare system, it’s like 1,000, each with its own rules, payment, etc. which you qualify for based on where you live, your military status, your income, your age, your opinions on various HBO shows, or your job. Depending on a certain permutation of those, you will change between these many different health systems.

Each state has its own rules and payment system around how someone qualifies for Medicaid and how providers get paid. Employers have a completely different set of laws that apply to them, and many of them become their own insurance companies. Veterans have their own thing. Jail has its own rules and payment system. Each college has a different health plan and set of services. The government runs some of the systems, health plans run some of them, your hospital might run their own, etc.

Having so many disparate payment and care delivery systems has many issues:

- People are switching between risk holders constantly. Let’s say you’re on Medicaid, but then you end up making enough money that you no longer qualify, so you switch to a plan on the individual exchange. Or let’s say you switch jobs. Each time this happens you’re automatically forced into some new health insurer, which means that no one actually cares about long term health outcomes. Instead, they only care about how much you’ll cost while you’re in their risk pool. It becomes risk hot potato as you switch between all these plans until you’re 65, get on Medicare, and the government essentially ends up footing the bill.

- As a result, we underinvest in preventive health and upstream risk factors because every payer assumes you’ll be gone to someone else by the time it would matter. Oh you want to eat a vegetable? That’s Humana’s problem, not mine.

- The risk pool gets all messed up. Insurance products only work when healthy people get insurance to help pay for the costs of the sick. However, with so many different pools of insurance, you can end up with inherently riskier or less risky pools depending on the characteristic that defines your entrance into it. For example, tech companies with mostly younger and affluent populations can create a pool with a much better risk profile and charge less for health services vs. Medicaid, which is low-income, or the Out-Of-Pocket employee risk pool, which has a high risk of institutionalization.

- The prices are different for each one of these systems even if you’re getting the same exact care at the same exact place. Because of this, hospitals will end up investing in facilities and building processes accordingly to acquire more “valuable” patients and get more money per patient from the plans that pay more. The Cigna PPO orange juice is $10 while the Medicaid orange juice is $3. Also, it’s actually Tang.

- This mix of prices also creates a reliance on cross-subsidization, which ends up impacting some patients more than others. This especially true in areas where a company is somewhat “mandated” to provide services. For example, hospitals will claim that they can’t make money servicing patients on Medicaid, which leads them to jack up prices on patients with commercial insurance who then pay much more.

- The administrative burden of keeping track of who’s on which plan is insane and, as a result, the prices are different for each plan. I wrote a whole thing about how Candid has to build extremely complex rules engines just to figure out who gets paid, but armies of people’s entire jobs are designed to just figure out who pays and when. If you want other examples, just mention the word “prior authorization” to your doctor and they’ll spontaneously combust.

Theoretically, the benefit here is that you can run different types of healthcare “experiments” in each of these different systems, which can be replicated and rolled out in other states or nationally. For example, the Affordable Care Act was a national scale rollout of a similar plan in Massachusetts called RomneyCare. I would love to see more of that kind of experimentation!

But absent that, it seems like the headache of having so many systems is a net negative.

Principal-Agent Problem

The buyers and users in healthcare are usually not the same people, and the two entities usually have different priorities (e.g. price vs. experience).

There are so many examples of this across the healthcare ecosystem. Benefits companies sell to your HR team, but you’re the actual user. Hospital administrators buy the tools that front-line staff end up using. Insurance carriers aren’t selling to you, they’re selling to your employer (which IMO is the most egregiously unique and bad version of this phenomenon; I wrote more on this here, and would argue is the #1 thing I’d fix in the US healthcare system). I could keep going for days.

There are many distortions that happen as a result of this:

- Usability of tools is deprioritized.

- Top down, sales-driven companies win contracts instead of product-driven ones.

- Buyers pick lower price options since those are the KPIs they’re usually judged on.

- I have to keep mentioning the principal-agent problem.

- Status quo is rewarded because there’s no upside for risk and brand names are easier to justify.

I’m most interested in investing in product-led companies in segments where the buyers and users are the same people e.g. dev tools, direct-to-physician tools, cash pay companies, etc. People are going to want to use better tools, and it’s about “when” not “if”.

Size as Means of Negotiating

Size matters…here. Most stakeholders sell their size as a big part of their value because as the industry continues to consolidate, leverage accrues to those with larger economies of scale. In other countries, the government is usually the largest entity, so it does all the negotiating.

This kicks off a terrible positive feedback loop. Your insurance company has to get bigger to negotiate with the hospitals, who are getting bigger because they need to negotiate with the larger insurance companies. This ain’t a scene, it’s a gah damn arms race.

There’s also a second loop. As the industry consolidates, more rules get put in place to make sure they’re not being bad actors + shift them to more “societally beneficial” arrangements like value-based care. However, that ends up increasing the complexity of contracts and compliance costs, which ends up creating the need to hire more people to adhere to those rules + manage back-office processes, which…ends up leading to more consolidation because overhead costs increase.

This actually connects to the principal-agent problem. Because pricing and cost containment is usually the main metric on which buyers are measured, the negotiating leverage of the company becomes the MAIN thing they’re selling. This also leads to sellers bundling together as many products as possible, even if they’re average, just to check the box for the buyer who wants one vendor to handle as much as possible. In other industries, companies are fighting for end user loyalty which they can aggregate for leverage (e.g. Amazon fights to get you so they can better negotiate with suppliers).

The industry focus on size is bad:

- Every part of the industry has consolidated to a handful of players who then can charge whatever they want. These end up increasing prices and admin needed as they fight each other, with costs that get passed on to patients.

- It makes it very difficult for new entrants and independent businesses to get started. Either they’re reimbursed so poorly that they die immediately, or they need to join some form of “group purchaser” that aggregates other small businesses but charge significant take-rates (e.g. pharmacies joining a PSAO to negotiate against PBMs…who themselves aggregate different payers). The coolest, unicorn startup you can think of is a log scale jump away from even coming close to the number of patients the incumbent represents.

- The lack of new entrants also means less small businesses to sell to, which is usually how innovative companies get started (start with small customers with a specific problem and then grow into more).

- It leads to worse quality across the board. Almost every company in the history of mankind has gotten worse as it grows. Imagine having ADP level quality…for literally everything in an industry because they’re all massive, feature and process bloated, etc. A particularly egregious example of this is hospitals, where the case was made to consolidate so everything could be under one roof, improving patient quality, and…that doesn’t actually happen.

- As companies become larger, they introduce much more consolidated points of failure when things go wrong. We saw this acutely during COVID but it was an issue even before, like when Hurricane Maria hit Baxter’s production plants in Puerto Rico and we had to ration saline in 2017.

“The natural disaster in Puerto Rico knocked out the manufacturing capacity for small-volume presentations of sodium chloride and dextrose at one of two major suppliers, and that could send a ripple effect throughout the U.S. healthcare industry…Sodium chloride and dextrose are vital drugs used every day in hospitals around the country, said Chris Snyder, drug information pharmacist at Cleveland Clinic, who manages shortages and recalls.

"We're talking about two manufacturers that support nearly the entire U.S. and one of them is out and the other manufacturer doesn't have enough supply to make up for it," he said.

- Oligopolies that form as a result of consolidation can have so much leverage that they start getting…creative with their contracts. For example, PBMs are now so large and entrenched that they make money from insurers who they negotiate on behalf of, but now also charge their counterparty, the drug manufacturers, in the form of rebates to get preferred placement. No one has a choice but to play ball because there are so few PBM options to choose from (which is why the FTC is now getting involved in antitrust). Hospitals have used several of these, including anti-steering clauses to box out competitors. As a cherry on top, these contracts are frequently black boxes, since they can demand that by claiming proprietary information.

We should want more small businesses in healthcare. They’re more innovative, they’re more deeply connected to their end customers, and they give the people who start them more fulfillment that goes along with higher ownership.

A Focus On Out-Of-Pocket Costs

The greatest trick the devil ever pulled is convincing patients their out-of-pocket cost is what they pay. Isn’t that right, Christian- sounding hospital system?

The bill you get when you visit the doctor or get a prescription drug is not how much healthcare is costing you. A lot of cost is indirect through premiums, wage loss, deductibles, and taxes. If people really understood that those lines for premiums and deductibles are coming out of wages before you get your paycheck, there would be riots in the street. Or at least a stern talking to with their bosses.

Most people can draw a straighter line of cause-and-effect when they get an egregious healthcare bill vs. the million small indirect costs they feel. Companies have been focused on making patients not “feel” the costs when they consume healthcare the same way I don’t “feel” anything.

These out-of-pocket games are designed to make it possible for patients to consume services from hospitals, pharma companies, etc., who then price at whatever they want. I mean I’ll be honest, if I hit my deductible in a given year I’m getting the full buffet for the rest of it. Scan me up and down, do every lab test, throw a couple 30-day albuterol refills on my tab. Zaddy United is taking care of me until January.

Because of this, no one can actually understand prices or have debates about the real prices. Every time someone wants to point out egregious prices, the response is almost always, “those are just the list prices but not what patients actually pay”. This statement is also dumb because uninsured patients or any patient that has a co-insurance tied to the “not real” list price is paying that price!

Plus, you start to see insane games played between health insurers and everyone else to reduce the out-of-pocket expenses patients actually pay, but allow them to consume more high-priced healthcare. The worst offenders here are the pharma vs. health insurance wars. An example.

- Pharmaco creates an expensive branded drug.

- Insurers/PBMs create cost sharing (e.g. copays) to dissuade using the branded drug

- Pharmaco creates copay assistance to cover the copay (or foundations to help patients pay copays, which gets the companies into some hot legal waters). The patient might only “feel” the copay, but the drug company can get paid by the insurance for the rest of it, which is in their favor.

- Insurance companies then create “copay accumulators” which prevent copay assistance cards from being counted towards your deductible.

- Insurance companies also work with third-party “copay maximizers” who figure out how much the drug companies are willing to give patients to help with their copays, and then increase the copay to that amount to milk the drug company for that money.

- Pharmaco sues the maximizers for taking advantage of them.

- No one really knows how much patients pay.

Makes sense! This system is functional! By warring over the out-of-pocket portion a patient pays for the drug, this insane shell game schema has now been created. Where do you think the fees spent fighting this war come from? You!! Indirectly!! Exclamation points because of how stupid this is!!!

{{sub-form}}

The Data Problem

Data is siloed, in different places/formats, and has a massive time lag. While this happens across the ecosystem, there are a few areas where I think this is the most egregious.

- Payment, price, and billing data - No one knows the prices of anything, so you can’t even have real conversations about how to reduce prices. Price estimates aren’t tied to reality at all, making consumer shopping fictitious. On top of that, the amount of time it takes for everyone to figure out who pays what is months. The fact that we are normalized to not knowing how much we’re going to pay until a bill shows up months later is insane; in no other consumer industry would that be tolerated. Plus, that uncertainty around payment takes a much bigger toll on small businesses vs. large ones.

- Health record and EMR data - The fact that your data lives in a million different health records, structured in different ways, and without portability to whoever you want, is a travesty. It’s unsafe since historical parts of the record should be used to inform current treatments. It’s an administrative nightmare - think about the number of times you’ve had to repeat forms or health history. It forces the healthcare system to use billing data for things that billing data shouldn’t be used for, largely because it’s more structured and easily accessible. It prevents innovation since companies who might be able to do interesting things with that data have not been able to access it even if patients want them to (though I’m hopeful this is changing). Right now, EMRs as a source of truth that don’t interoperate means building applications for better care rests on the IT teams within hospitals (who, frankly, don’t care a ton about solving these issues).

- Data standards - The data standards currently in use in healthcare either don’t encode a lot of the actually useful information they should or they take forever to roll out because they’re managed by consortiums and non-profits. Without these agreed upon standards, it becomes a massive pain in the ass to actually make data workable or build third-party applications that can be used with all the relevant stakeholders.

The lack of data liquidity and the delay in information robs patients of their agency. It robs physicians of their ability to know how much things cost their patients. It makes it difficult for businesses to use data in smart and efficient ways. It prevents us from answering key questions that would progress healthcare forward. It’s the reason why I still need to learn how to use a fax machine in the year 2022, yet it’s the same year we may have created a sentient AI. Crazy how that works.

What is quality, what is the price of it, and who determines it?

Everyone wants “high quality care” in the US and also most likely supports innovation. But, it’s not super clear how we decide what quality care is and what we should theoretically be willing to pay for innovation.

- How do you know if someone is a “good doctor”? Is it the doctor that works at a name brand institution or the one that’s done the surgery you need a million times? How much more should the best doctor be paid than the median doctor? Should patients get a discount if they choose to go to the average doctor?

- This manifests frequently in scope of practice or platform fights. Physicians might say that a nurse doesn’t have as much training in X or patients might get misdiagnosed if it isn’t a face-to-face visit. It could be true, but should patients be allowed to assume that risk themselves (especially if cheaper)?

- In a value-based care contract, the measures of “quality care” are all across the board (which I talked about here).

- For incremental improvements in drugs (e.g. combining two separate pills into one pill to make adherence easier), should we extend patents? That combination is probably worth more societally, but how much more?

- Quality can also be used against us. Hospitals spend a lot of time convincing the public that they’re the cutting edge of medicine with new gizmos to attract quality docs + convince patients that they should make sure to have the hospital in-network. Have you ever seen a hospital ad where the hospital sells itself on being cost-effective?

Innovation and high quality care come at a price, and it’s not clear we’ve agreed who the judge should be and where that money should come from. Everyone probably agrees that any volume-based healthcare business model is the root cause of many downstream issues, but there isn’t a clear business model to move to when we can’t agree on what “value” or “quality” is.

Structural system failures and unhealthy lifestyles

The US social safety net is eroding and upstream structural issues are leading to downstream poor health.

- Food deserts lead to poor nutrition, which lead to chronic disease and the complications that come with it. But also, massive portion sizes and relatively sedentary lifestyles don’t help.

- Shortages of affordable housing are making it impossible for people experiencing homeless to get re-housed, instead experiencing all the downstream health issues associated with housing instability (drug use, poor post-hospital recovery, mental health issues, etc.)

- Air quality, especially in lower income neighborhoods, is exacerbating respiratory issues.

- Structural racism that results in biases in care, lack of coverage, etc.

- Financial instability is leading people to make tough decisions around getting medical care at all. Ironically, medical debt is one of the biggest culprits with an estimated 41% of adults in the US dealing with healthcare debt.

“About 1 in 7 people with debt said they’ve been denied access to a hospital, doctor, or other provider because of unpaid billsl. An even greater share ― about two-thirds ― put off care they or a family member need because of cost.”

Healthcare Meme

It’s hard to get patients to care about healthcare when their basic needs aren’t being met. These are structural issues that need serious policy reform to solve.

It’s also unclear where the line of healthcare and social safety net programs should be drawn, and when something is the purview of the healthcare system vs. government programs. I’d argue that there are reasons to be cautious around medicalizing social determinants of health and relying on private companies to make that determination.

Healthcare’s labor problem

System failures exist not only for patients, but frontline staff and clinicians as well. Burnout is at an all time high, debt-to-income ratios seem to be getting meaningfully higher for people going to any healthcare programs, and more clinicians feel overworked and are planning to retire early. This creates a dangerous spiral where frontline staff leave, giving more work to the remaining staff, who then get burnt out and leave.

COVID really highlighted how much worse the conditions and life of healthcare workers have become, especially relative to other industries. Baumol’s cost disease talks about how as certain sectors become more productive they attract labor, making it even more expensive for the less productive industries. We’re seeing that happen acutely in healthcare.

“The average starting pay for an entry-level position at Amazon warehouses and cargo hubs is more than $18 an hour, with the possibility of as much as $22.50 an hour and a $3,000 signing bonus, depending on location and shift. Full-time jobs with the company come with health benefits, 401(k)s and parental leave. By contrast, even with many states providing a temporary Covid-19 bonus for workers at long-term care facilities, lower-skilled nursing home positions typically pay closer to $15 an hour, often with minimal sick leave or benefits.

Nursing home administrators contend they are unable to match Amazon’s hourly wage scales because they rely on modest reimbursement rates set by Medicaid, the government program that pays for long-term care.

Across the region, nursing home administrators have shut down wings and refused new residents, irking families and making it more difficult for hospitals to discharge patients into long-term care. Modest pay raises have yet to rival Amazon’s rich benefits package or counter skepticism about the benefits of a nursing career for a younger generation.”

We are going to have a serious problem in the near future if healthcare can’t attract people to work in it, especially as the population ages and healthcare needs increase. I recognize the irony of saying this as a person that writes a newsletter after shying away from going into healthcare directly.

Software can increase the productivity of frontline staff, but it can’t assist someone with their daily living needs. We’re still going to need people to do that for a long time. Until we all live in the metaverse, that is.

Incremental fixes vs. total overhaul

Our current solution has used band-aids to try and fix US healthcare, which has not really been working well. This is partially because there's a political deadlock where no one wants to give an inch. Politicians getting judged in short time frames means incremental wins that play better to voters.

But there’s also the issue that a massive overhaul is going to be good for some and bad for others, there’s no such thing as a perfect system, and everything consists of trade-offs. And there’s a lot of money flowing through the system dedicated to preventing it from changing too much.

Conclusion

I’m sure there are lots of other issues I missed - this country’s healthcare system is such an absolute hellscape that foreigners can’t tell if the things posted about it online are jokes or not. But I think this encompasses a lot of the core issues, which manifest in different ways.

This might make me sound jaded as hell, but I’m not. You gotta point out the problems so you can fix or debate them, right?

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. ”I got 99 problems and most of them are healthcare related”

Twitter: @nikillinit

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

Thanks to Shashin Chokshi, Morgan Cheatham, and Dan O'Neill for reading drafts of this

P.S. If you missed the report and discussion on the Future of EHRs, you can get the slides and recording here. Did we solve the future of documentation? Only one way for you to find out.

{{sub-form}}

---

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

Interlude - Courses!!!

See All Courses →We have many courses currently enrolling. As always, hit us up for group deals or custom stuff or just to talk cause we’re all lonely on this big blue planet.