Cool Ideas For Dentistry + Medicine With Nisarg Patel

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveNetwork Effects: Interoperability 101

.gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Today I’m interviewing Nisarg Patel, resident at UCSF, co-founder of Memora Health, and writer extraordinaire. [His twitter, Linkedin]

We talk about the cloning device he uses to do all of these things, as well as:

- Company ideas he’s seen in the hospital

- What actually happens in the operating room

- What an integrated dental/medical system might look like

- What dental and medical do well/poorly compared to each other

- Exciting upcoming pieces of legislation he’s watching

- And more!

1) What's your background, current role, and the latest cool healthcare project you worked on?

My primary role is as a resident physician in oral and maxillofacial surgery at the UCSF Medical Center, where I'm interested in facial reconstructive and microvascular surgery, and also do research in computational cancer genomics. I also work part-time on the health care team at Bessemer Venture Partners, focusing on biotech investments, and have been a contributing writer riffing on health policy and medicine for the Washington Post, Financial Times, Politico, and Slate, among others.

[NK note: Nisarg is never allowed to meet my parents]

Five years ago, I cofounded Memora Health, a digital health company aiming to automate the communications and administrative workflow for ambulatory care, and have worked with our (quickly growing) team as an advisor during residency. I'm incredibly excited by how well we've been able to take disparate clinical and administrative data, like free text notes, call logs, discharge instructions, and patient-reported outcome surveys, and structure those pieces into standardized care pathways and measurement tools that can both be shared (and benchmarked) between institutions and used to gauge quality of care.

My background has largely been way too much time in school. I was born and raised in Phoenix, Arizona, studied biotech and political science at Arizona State, medicine at UCSF, and both dental medicine and biomedical informatics at Harvard Medical School and the Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology program. That being said, the chunks of time I spent immersed in different disciplines came together in hindsight as we now see so much of what happens in this industry, from care delivery to drug development, influenced by Capitol Hill. Additionally, seeing the stark differences in the patient experience—in terms of both care and cost—for dentistry vs. medicine vs. surgery has helped me frame how varying financial incentives and policy guardrails influence both customer service and quality of care.

2) As a resident surgeon/founder, you must see like a million potential company ideas or processes that could be improved. Are there a few you can share?

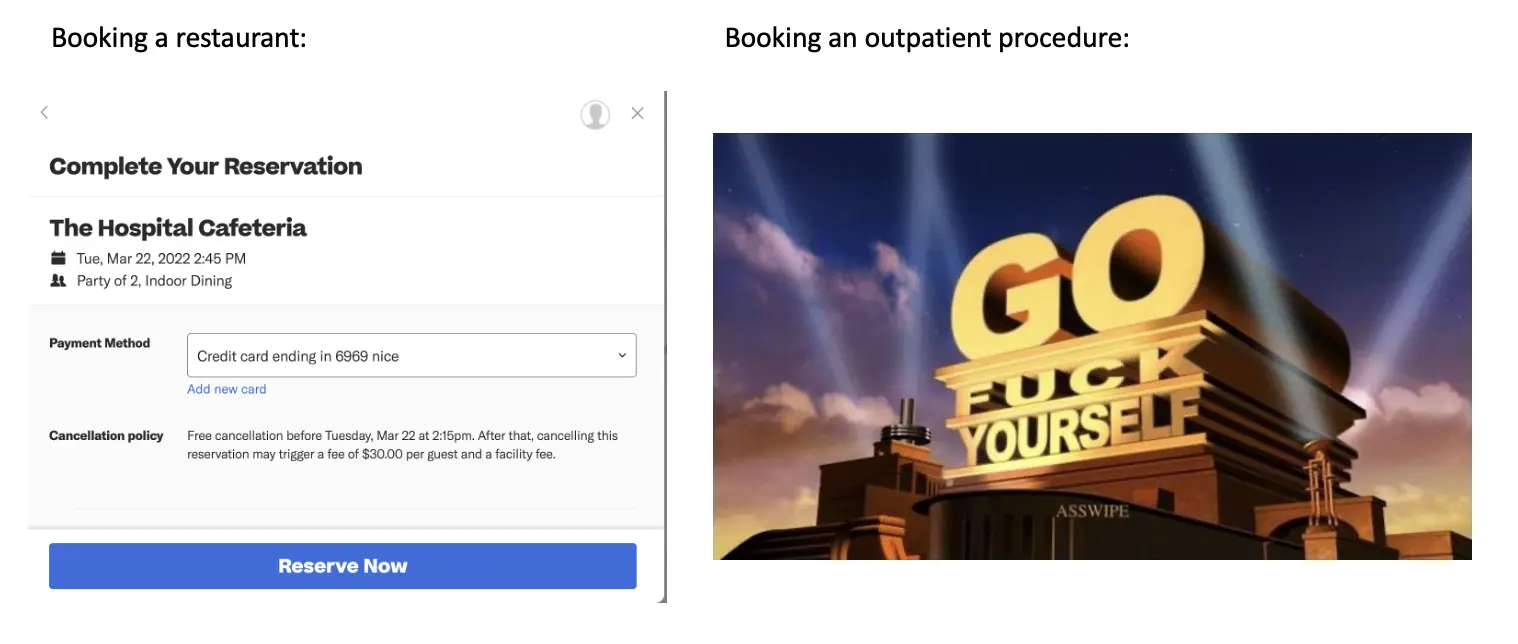

Surprisingly, one of the biggest frustrations I've experienced across multiple hospital sites is converting new patient requests for appointments into visits. A couple close friends have mentioned offhand that they've been unable to get an appointment with my department over the phone. This is a multifactorial problem, and can be due to staffing constraints, uncertainty over insurance coverage, deprecated voicemail systems, and outdated contact information. I'd love to see a system make booking hospital outpatient visits as easy as booking a reservation on OpenTable/Yelp/Resy.

There are plenty of examples where the principle of DRY (don't repeat yourself) code could be applied to day to day hospital operations. Physical paperwork, such as patient intake and consent forms, often only slightly varies between patients, and would benefit from pre-completed sections. My guess is that this is why Epic eventually developed 'smart phrases' for providers to quickly build and use digital note templates for different types of visits and procedures. Similarly, whether in the clinic, ED, or the operating room, I'm often collecting the same combinations of medical supplies and surgical tools to prepare for a procedure. Bundling these into kits, which has been done *to an extent*, would go a long way for efficiency and predictable inventory management.

One more niche process I'd like to see improved is the intensive care unit monitoring of patients who have had free flap reconstructive surgery, in which one part of the body, like the fibula and associated large blood vessels, is removed and reshaped for placement in another part of the body that was previously diseased, like a tumor in the mandible. Residents and nurses typically check on the integrity of the re-attached blood vessels using a small doppler ultrasound hourly overnight, and rush the patients back to the OR if the doppler indicates that a re-attached vessel has failed. Given the periodic nature of these checks, a continuous connected sensor that can immediately alert staff if something is amiss would both relieve pressure on staff and offer more timely notification of a patient's condition.

3) I don't think most people understand what the OR is actually like. What does the process actually look for a routine surgery you're called in for? What are the dynamics of the OR like?

Most importantly, everyone has a defined role, and clear communication is paramount. As a junior resident, I'm typically the first surgeon in the OR and help set up the room, which means pulling out the right-sized sterile gloves for everyone and grabbing materials to both drape the patient and secure their airway (i.e. via an endotracheal or nasotracheal tube) after the anesthesia team intubates them.

After we've gone over risks/benefits and the consent form with the patient, the patient is wheeled into the OR from the pre-operative area, moved from their gurney to the OR bed, and put under general anesthesia by the anesthesia team. We'll then secure the tube in place, drape the patient in sterile sheets, and do a 'time out', which is essentially a checklist primarily confirming the patient's name, medical record number, procedure (and critical details), and location (right/left/bilateral) as well as make sure everyone in the room knows each other's name and role (which helps with intra-op communication!). The team typically involves the surgeon(s), usually an attending and one or more residents, the anesthesiologist or CRNA, the circulating nurse (not scrubbed in, monitors patient/staff during procedure), the scrub nurse (scrubbed in, prepares and hands tools to the surgeons), and a medical device sales rep (for cases where we're using niche or custom-made surgical tools/hardware).

We'll announce major portions of the procedure that are relevant to the rest of the OR team in real-time, such as placing gauze in the throat to prevent aspiration, injections of local anesthesia, the first incision, portions of the procedure that may lead to significant changes in blood pressure, and the start of 'closing', i.e. beginning to suture the incision site(s) closed.

When the procedure is over, the anesthesia team wakes up the patient, we all wheel the patient to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), and talk with the PACU nursing staff about the summary of the procedure, any complications, and immediate post-op management, and the discharge plan for the patient, i.e. whether they'll be admitted as an inpatient or go home/to a SNF that day. If it's an outpatient procedure, we'll typically follow-up in one week in our hospital clinic. If it's an inpatient procedure, the resident on-call will see the patient during evening rounds and manage any issues that arise overnight.

4) You've frequently talked in the past about better integrating dental care into health more holistically. Why do you think primary + dental isn't more common today? In your view how would you integrate them?

The lack of integration is predominantly anachronistic (good interview on the history here). Today, the largest reason for the split is the majority of the dental profession's desire for autonomy/independence. General dentists (reasonably) don't want to face downward pressure on fees from typical medical insurers or be governed by the same oversight laws. Combining primary care and dental services under a single roof that takes on capitated risk would be a good place to start; CareMore Health has begun to do this with one dental clinic in LA, albeit with some complications due to varying medical vs. dental insurance coverage. Kaiser is trying this model in the PNW. However, I think part of the reason this model hasn't taken off yet is because we don't have enough high-quality research linking poor oral health with consequences to systemic health (partly because it's hard to find, structure, and link well-documented dental and medical information for a single patient given the small number of hospital dentistry departments). That being said, because we can intuit a relationship between poor oral health (e.g. periodontal infection) and systemic health (e.g. endocarditis, chronic kidney disease, asthma) and there has been some associative (albeit not quite causal) evidence published, every patient undergoing cardiothoracic, transplant, and (some) neurosurgical procedures in the hospital needs a 'dental clearance' from either hospital dentistry or oral/maxillofacial surgery prior to the operation. This is because an undiagnosed dental infection/risk of infection could seed a post-operative infection and increase the risk for sepsis at a time when the body has fragile wounds/incisions, may be immunosuppressed (in the case of a transplant procedure), and trying to recover from major surgery.

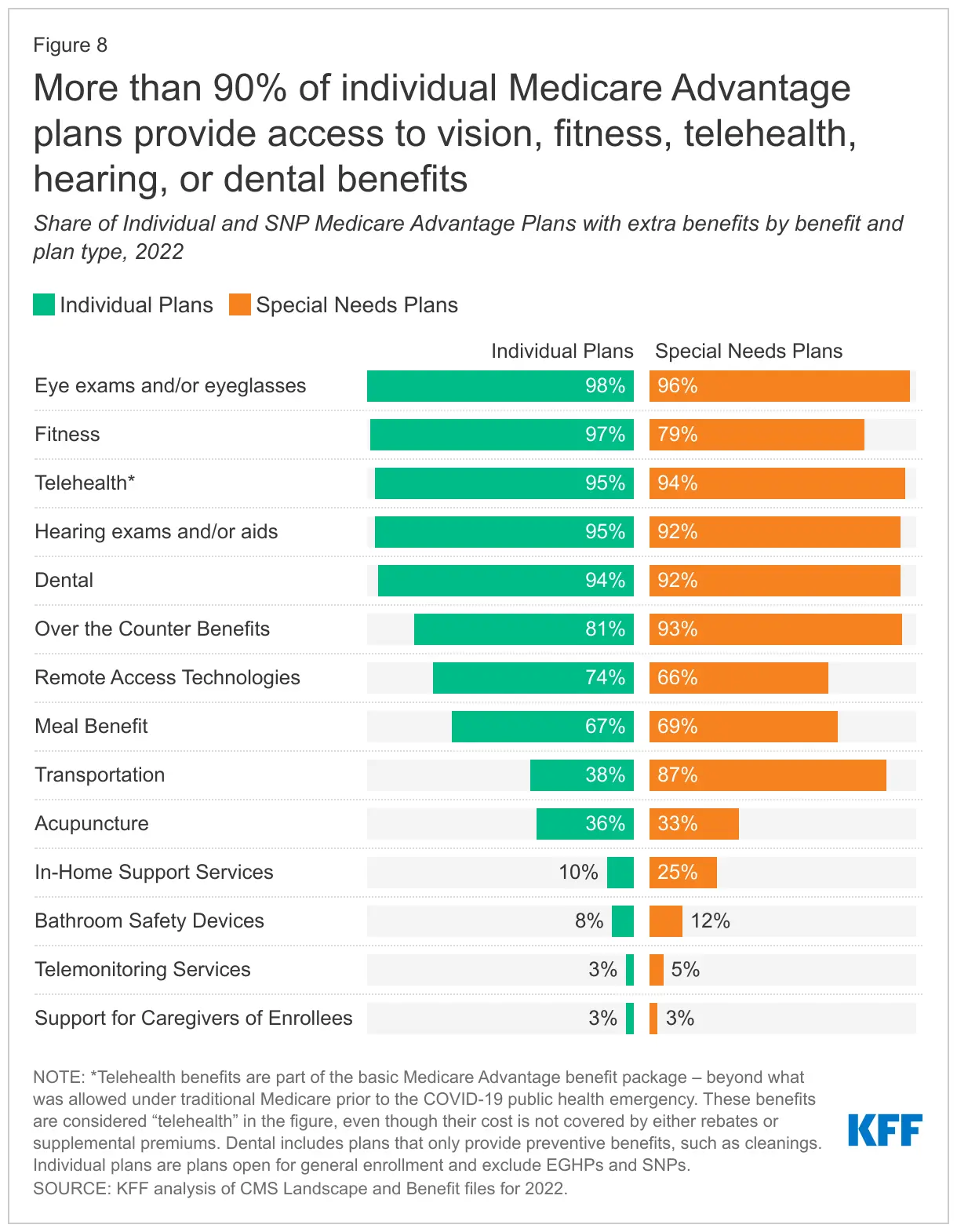

Like CareMore, the best place to start integrating primary and dental care is in Medicare Advantage plans (due to their capitation model and demographic), and if I had a legislative magic wand, I'd have Medicare cover dental care as a basic benefit as well. Fifty percent of Seniors reported not visiting a dentist in 2019 due to cost and only 12% of Medicare beneficiaries reported having some type of dental coverage. More concerning, approximately 20% of Seniors have untreated dental caries and need care, and another 20% have lost all their teeth. Given the stronger retention of beneficiaries among MA plans relative to commercial plans, the more immediate and visible downstream health effects from poorly cared for seniors, and the familiarity of MA plans with non-direct medical care services (e.g. home health, nutrition), adding dental services is worth testing in a high-risk population (e.g. those with Type II Diabetes, who are more prone to infection). Given that the largest challenge will be paying for the massive upfront costs of providing dental care (office space, dental chairs, imaging, tools, consumables), a good model for an MA plan to gauge cost savings/loss per beneficiary with integrated dental care would be to create a network of partner dentists and offer attractive fee-for-service rates in the short-term.

[NK note: Dental Benefits are also one of the top extra benefits offered in MA plans, and one that actually gets used frequently]

5) Since you have experience on the dental, medical, and surgery side of things - what do you think each does well and poorly when it comes to patient care?

Dental services do a strong job of engaging patients between visits (e.g. automatic scheduling, phone/mail/sms reminders), partly because insurance reimbursement is often contingent on time between services (e.g. a dental cleaning every six months is covered), and offer a *relatively* good customer experience within the clinic (lower wait times for both an appointment and in the waiting room relative to medicine, faster time from consultation to treatment). Dental services suffer from a) poor insurance coverage, leading to significant forgone care, subsequent complications, and potential need for more invasive eventual treatment (e.g. stronger anesthesia, extraction of teeth, surgical management of a jaw infection) and b) a relatively poor evidence base compared to medicine, largely because there hasn't been a *strong* historical culture of dental research and associated training/community, whereas that culture has flourished in academic medicine.

Medicine/Surgery do a really good job of documenting everything going on with inpatients (medicine typically better than surgery). This level of detail means someone could find underlying conditions or social determinants of health in prior notes that a patient might have not mentioned during the current visit that influences their diagnosis and/or care plan. However, that level of documentation can sometimes be a double-edged sword, leading to 'needle in a haystack' type situations when it comes to searching through charts. Although the documentation volume is a side effect of Meaningful Use and insurance reimbursement requirements, there's definitely a culture among some departments to write the most thorough note possible.

6) As someone actually on the frontlines, what has surprised you about the hospital response to COVID? Are there changes you hope stay permanent?

Given what we knew about asymptomatic spread by April 2020, I was surprised that many hospitals, including my own, initially opted simply for daily symptom screenings and temperature checks as opposed to regularly testing asymptomatic health care workers. Our resident work rooms are small and we don't have isolated break rooms to eat meals, so naturally, even with safeguards in place, the close proximity and mealtimes without masks increase the risk of transmission. In 2020, a Boston Globe article placed the blame of rising hospital COVID19 cases on 'weary' health care workers (unfairly imo).

In that aftermath, Brigham and Women's Hospital (the subject of the Globe piece), UCSF, and other hospitals offered voluntary asymptomatic testing for health care workers.

I can't think of any hospital changes that I hope will stay permanent. Between the staff social distancing, difficulty recognizing colleagues across departments (due to masks/face shields), lower operating volume, and the heartbreak of caring for the COVID19 patients themselves, hospitals are a much emotionally tougher place to work in right now.

7) What's an upcoming piece of legislation (either proposed or going into effect) that you're most excited by, COVID-related or not? Why is it a big deal?

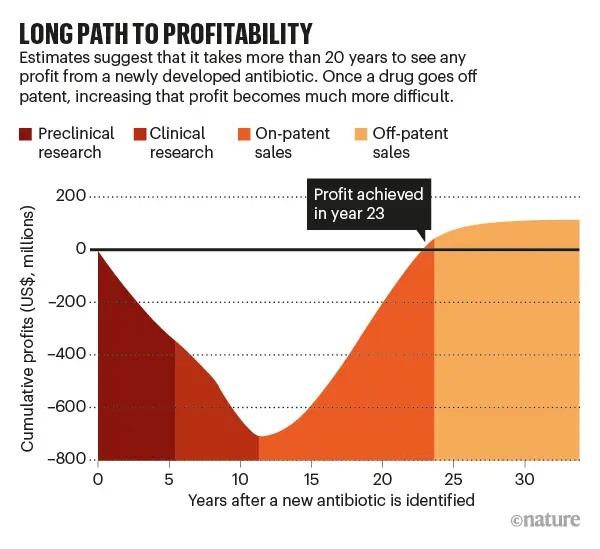

One bill that I chatted with hill staffers about over the last couple years (and had the opportunity to cover for Slate) is the PASTEUR Act, which aims to incentivize new antimicrobial development through a guaranteed government subscription to newly developed therapeutics, particularly as we see rising rates of antimicrobial resistance among microorganisms and big pharma leaving the sector.

Antibiotic commercialization suffers from a market failure secondary to the nature of evolutionary biology. When you create a novel, powerful antibiotic, doctors only use it as a last resort (to prevent even further antibiotic resistance). This is good for public health, but bad for biotech returns; our most clinically valuable drugs don't see their commensurate financial value because sales volume is low. This causes a lot of antibiotic startups to fail and investors are hesitant to pump more money into the therapeutic area.

We've historically seen a lot of 'push' incentives from BARDA, WHO, CARB-X, and other entities to increase R&D funding and from prior legislation (e.g. GAIN Act) to provide a longer market exclusivity period and faster regulatory review, but none of these initiatives address the commercial market imbalance. We've essentially exhausted the repertoire of push incentives that exist.

PASTEUR, if passed, would be a notable 'pull' incentive for antimicrobials. In a nutshell, the US government would enter into agreement with a biotech co to pay a set contract value for any federal beneficiary who needs the drug. This de-links reimbursement from clinical volume, and instead bases the price on the 'societal value' of the treatment (from a list of favorable drug characteristics, e.g. new drug class, favorable resistance profile, oral delivery, is it manufactured domestically?, etc). The UK and Sweden have rolled out these prescription models for antibiotics and Louisiana and Washington state have used it for otherwise-expensive Hepatitis C treatments. This program allows the US to 1) create a functional market, 2) finally price drugs on value, and 3) prevent antimicrobial drugmakers from 'pushing' drugs onto physicians and contributing to antimicrobial resistance. Doctors can use as much or as little of the drug as needed without financial consequence to the drugmaker.

An alternative argument would simply be for biotech companies to set high prices for new antibiotics, but all inpatient-administered antibiotics are wrapped into a DRG payment for the condition being treated (as opposed to under Medicare Part B), which pressures hospitals to pick non-expensive drugs. Another bill, the DISARM Act, is trying to remove the inclusion of inpatient antibiotics in Medicare DRGs and into Medicare Part B. Although this would allow drug companies to raise price of antibiotics and receive a more 'fair' reimbursement, it consequently increases the reward for "over-commercialization", contributing to more antimicrobial resistance. Lastly, encouraging high drug prices is a political non-starter and legislative committees aren't fond of DRG carveouts as they could be a slippery slope.

[NK note: Reminder we talked about what DRGs are + how they pay for new tech in the Viz.ai post, but in this case you don’t want to incentivize too much use of the new tech]

8) I've been thinking a lot about why physicians choose to go work at hospitals (e.g. how does Mayo Clinic attract such high quality physicians). If I started a hospital today and wanted to pitch you on coming to work there - what would attract you to join a new hospital vs. the established names? Would it even be possible to convince you?

This typically varies by a physician’s career goal. Interested in climbing the academic ladder? Go to a prestigious medical center that excels at the type of research you're interested in. Interested in purely clinical work? Go to a medical center that excels at your chosen specialty and/or serves the population you’d like to care for most. Beyond those, I'd say choosing a hospital depends on location, salary, culture, career opportunities, and (debatably) prestige. Mayo has a both a unique and supportive hospital culture and invests a lot of resources into attracting residents and attendings. I absolutely loved the hospital during my own residency interview there, but couldn't get over the location/weather. I thought I got the best of all worlds at UCSF.

Hospitals might recruit star physicians away from other academic medical centers with promises of funding, resources (e.g. equipment, staff, research institutes), salary, or room for higher academic advancement. If you were starting a new hospital from scratch, establishing a supportive culture along with resources for an interested physician to pursue the work they're interested in without worry of lack of time/funding would be an ideal place to start. We’re starting to see this model spin up in biomedical research (e.g. Arc Institute, Altos Labs).

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “hyper aware of my imposter syndrome now”

Twitter: @nikillinit

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

{{sub-form}}

---

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!!

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

Selling to Health Systems (starts 10/6) - Hopefully this post explained the perils of selling point solutions to hospitals. We’ll teach you how to sell to hospitals the right way.

EHR Data 101 (starts 10/14) - Hands on, practical introduction to working with data from electronic health record (EHR) systems, analyzing it, speaking caringly to it, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

Selling to Health Systems (starts 10/6) - Hopefully this post explained the perils of selling point solutions to hospitals. We’ll teach you how to sell to hospitals the right way.

EHR Data 101 (starts 10/14) - Hands on, practical introduction to working with data from electronic health record (EHR) systems, analyzing it, speaking caringly to it, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.