Healthcare in Jail

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

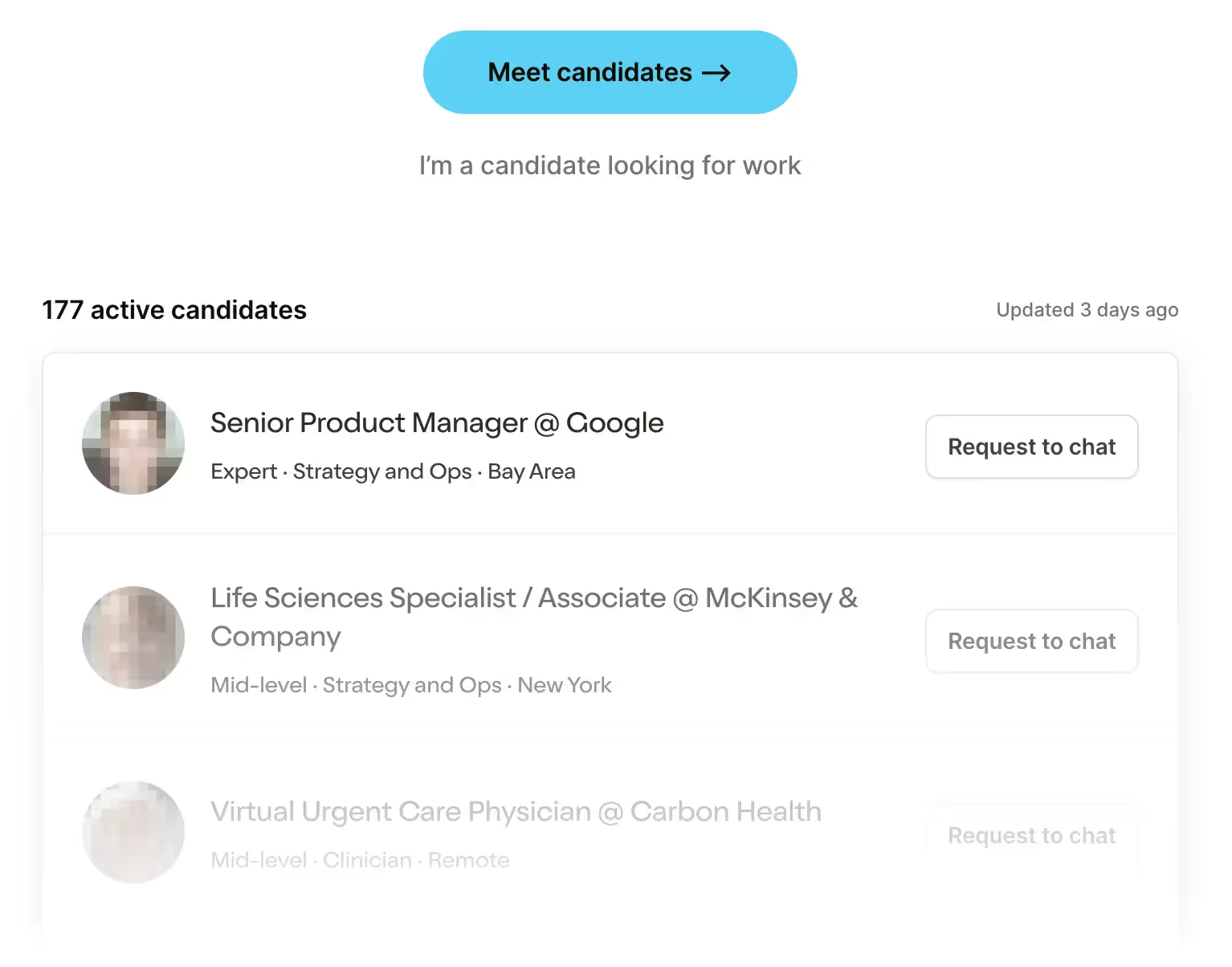

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveClaims Data 101 Course

.gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

A frequent theme of this newsletter is how the US is actually a complex web of parallel healthcare universes that live alongside each other. The Veterans Affairs system, self-insured employers, Medicaid, Medicare, etc. all have different rules for how care is delivered and paid for.

One of these parallel systems is the jail and prison systems. Against the backdrop of protestors calls to demilitarize the police, the jails in the US have proven to be a petri dish for COVID to spread. One paper suggests that a significant contributor to cases in Chicago was due to people going in and out of the Cook County Jail.

The data suggest that cycling through Cook County Jail alone is associated with 15.7 percent of all documented novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) cases in Illinois and 15.9 percent in Chicago as of April 19, 2020.

Looking state-by-state gives glimpse into just how bad some states have it. The Marshall Project has been tracking this closely.

I thought it would be timely to take a quick overview of the jail health system (I’ll tackle prison later). This is all very new to me, but I’ve read about this for 3 days which makes me an expert.

Jail + Prison Structure

First, it’s worth highlighting the difference between jail, prison, and community supervision (aka. probation, parole, halfway homes etc.)

Prison and jail might end up getting used interchangeably in conversation with non-lawyers (aka. generally better conversations), but they’re actually very different.

Jails are designed for short term stays (between 10-30 days) for people awaiting trial or convicted of misdemeanors. This means there’s a ton of turnover within a jail stay (~60% weekly turnover) and both the arrival time of a person and the discharge time is unpredictable. Capacity fluctuates quite a bit, and the healthcare needs/costs are variable since one very sick person can totally tilt the budget. Jails are also usually governed by local law enforcement.

Prisons are typically longer term stays for people convicted of felonies. Their entrance and exit dates to a facility are quite predictable. These are governed by the state and Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). I’ll go into the prison side later.

Demographics and conditions in jails

There are about 2.3M at a given time in the jail-prison complex. The bulk of those are spending longer term sentences for violent crimes in state prisons. About 615K are in local jails, with more than 75% of those sitting without conviction. There are ~3200 jails that have 10M+ admittances per year.

As you might imagine, the jails are disproportionately filled with black and male inmates, which only contributes to the race/health inequities I talked about previously. On the health front, inmates within jails are much more likely to have a chronic disease, and nearly 3x as likely to have an infectious disease as the general population.

A look into the mortality data for jails suggests there’s a significantly higher burden of heart disease and suicide vs. the regular population. Heart disease in particular is worth keeping in mind when considering COVID mortalities were particularly bad amongst patients with underlying heart conditions. Data suggests suicide are 2x more prevalent in jails vs. prisons, and more than 3x the general population on a per capita basis.

Payment And Services Structure

Most jails seem to outsource their healthcare services to a third-party to handle. In some cases this is a nearby hospital, but in many cases this is a healthcare services company that targets correctional health specifically (Wellpath, Corizon, ArmorHealth, etc.)

Some services provided would include: screening patients at intake for medical, mental, and dental issues, administering medications to patients, provide transport to hospitals if patients have an emergency, provide access to psychiatrists and nurses when inmates need care., etc.

But who pays for this? Well a very important point to bring up is the fact that inmates are excluded from being covered by Medicaid. Medicaid cannot cover inmates unless they end up in the hospital for more than 24 hours. The payment falls on a combination of the jail, the local county (and therefore county taxpayers), and the patient who in many cases has to pay small co-pays for a services.

Usually jails will send out RFPs, and it will be some combination of hourly rates for specific types of labor, costs for specific services, flat yearly fees, and/or per person $. This PEW report goes in-depth into a lot of different versions.

I’ve seen various estimates, but the amount jails spend on these outsourced services is wildly variable. One report ballparked it at 10-15% of the total jail budget, but there’s clearly extreme variation.

When someone goes to jail, their health becomes the issue of the jail and county. Not having access to Medicaid means the state/federal government can’t help contribute funds so the burden is entirely on the local county. The reimbursement rates for an incarcerated person are usually lower than Medicaid, so hospitals don’t want these patients. I’m guessing the correctional care companies can make this model work because they don’t have to deal with the overhead, it’s all in the jail.

Also without Medicaid coverage there’s a sudden interruption in care/coverage for the inmate since they’re forced to enter this new healthcare system. Another part of US healthcare where you’re forced to switch your insurance/care.

Quality of care?

One of the dark ironies is the fact that incarcerated people are one of (if not the only) group in America who are GUARANTEED access to healthcare and mental health services. But this highlights the difference between “access” and “quality”.

An extremely big question mark as I was researching was how quality of care was measured. This is a difficult question because the jail population turns over extremely quickly, are disproportionately sick, difficult to track long-term outcomes, etc.

Right now, most jails and prisons seem to be focusing on providing the necessary amount of care to meet the Eighth Amendment’s definition of “adequate medical care” that inmates are entitled to. Most jails don’t seem to be clamoring to go above and beyond since they’re not exactly competitive businesses.

But if you look at the RFPs that jails put out for contracted health services, they’re focused on cost, services available to inmates, and number of members on staff. Several ask for different utilization metrics, but nothing around payments being tied to them. Some have metrics tied to response time to inmate requests, and some have penalties for not turning things around quickly enough.

I thought this RFP from Sedgwick County was pretty good because it required a mutually agreed upon third-party to assess if these metrics were met, random sampling of inmates to assess the metrics, and determined whether the company would be entitled to the amount in holdbacks. Most of the RFPs do not look like this and there is very little standardization.

In fact jails ironically can’t seem to police these correctional health providers since rarely is the data captured properly. The sheriffs/jailers are also not healthcare experts so they find it difficult to assess the care being delivered.

While counties have the opportunity to review medical records — or conduct audits — sheriffs rarely do so unless something went horribly wrong. Instead, they typically deferred to private companies, CorrectHealth or other providers, to fix its own systems.

Who will watch the Watchmen?

There generally seems to be very little oversight into the performance of the healthcare providers here. One of the owners of Wellpath actually said:

He also pointed out that Wellpath routinely indemnifies state and local governments from all legal costs in cases involving alleged medical mistakes. “We bear the risk of malpractice,” he said, so “we’re incentivized to provide quality care.”

What? If malpractice was all it took to deliver quality care we wouldn’t have spent the last 10+ years arguing the definitions of what “value-based care” is. Plus, you’re really telling me that a private-equity backed billion dollar company has fear of lawsuits from the most vulnerable members of society? There’s a reason almost every single suit against them gets settled outside of court.

Also later in the same article, there’s this tidbit:

In the pharmacy, medical technicians prepare medications for “med pass”—when a Wellpath employee takes medications from cell to cell on a cart. Novacek now tracks something to do with the “initiation of essential medication.” I don’t know exactly what she’s monitoring, because Wellpath considers its specific performance metrics proprietary, so the county couldn’t tell me.

You know something is shady when the performance metrics for a taxpayer-funded contract are considered proprietary.

Things worth looking deeper into:

- Half of the people that end up back in jail identify as having a substance disorder, yet almost none of the Request For Proposals for health services included Medication-Assisted Treatment. Not only does this present a huge issue for withdrawal symptoms, but also presents an opportunity to begin substance abuse care in the jail that a patient can more seamlessly role into when they’re released.

- The above also shows more than a quarter of offenders lack health insurance. A perfect chance to enroll these groups into Medicaid.

- There’s very clearly a tension between the healthcare service providers + officers in the jail and the inmates when it comes to whether the patients are “faking it”. Many of the deaths, especially from heart attacks and severe withdrawal, seem to have this aspect in the articles I read. Equipping jails with more objective measures (e.g. medical-grade wearables, point-of-care diagnostics) could help ease this tension.

He suggested that Laintz had been deliberately hyperventilating to produce his symptoms, in an attempt to be sent to the hospital. “There is no medical reason for him to go,” the administrator said, and asked her to tell her son “to quit hyperventilating and to coöperate with us.”

…when Laintz insisted on being taken to the hospital, a sergeant at the jail overruled the assistant and sent Laintz in a police car to the St. Mary-Corwin Medical Center. There, according to his lawyer, doctors diagnosed dehydration, sepsis, pneumonia, and acute renal and respiratory failure.

- Many of the healthcare service providers that focus on jails are private equity owned. Now, unlike most people in healthcare, I actually don’t view private equity as some monolithic evil. But in areas where the patients are unable to make choices (jails, emergency departments, etc.) the operational efficiencies are more about “what can I get feasibly get away with” instead of making a company more competitive in the marketplace.

- Capitated plans where the healthcare service providers get paid a flat rate per head for providing services to jail inmates are way weirder when the audience is (literally) captive. Because inmates have way less choice around when they can go to the emergency room (the staff at the jail has to decide that), the service providers have an insane amount of control over the hospital admission.

Conclusion

Healthcare in jail seems to be an exaggerated microcosm of all our healthcare problems in one place.

- It’s very difficult for us to actually figure out what quality/value looks like and get the data needed to make those assessments (evaluating correctional health services vs. literally any value-based care program).

- The people in charge of measuring quality (jailers vs. HR departments at companies) are expected to be healthcare experts who can diligence these solutions.

- The patients in this system are currently forced to churn from their insurance (when they enter and leave jail vs. when you enter and leave a job).

- Consolidation, local monopolies and the illusion of choice (especially in rural areas) is making everything much more expensive.

- These issues disproportionately affect groups of color.

I could keep going but you get the gist. Instead of viewing jail inmates as a place to offer the bare minimum required coverage, this can be viewed as an opportunistic touchpoint to better serve some of our more vulnerable and costly patients. When we know health issues have a higher prevalence in a specific population, shouldn’t we figure out ways to deploy MORE resources there, not less?

Look at the differences between amount of screening and testing done for jail inmates vs. prisoners. Most jail inmates are not charged with anything and are going to re-enter society. Ignoring the fact that this table also points to the earlier issues of accountability, it also shows a missed opportunity to help a group in-need.

Anyway, from my grand total of

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil

Twitter: @nikillinit

Interlude - Courses!!!

See All Courses →We have many courses currently enrolling. As always, hit us up for group deals or custom stuff or just to talk cause we’re all lonely on this big blue planet.