How do hospitals spend money?

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

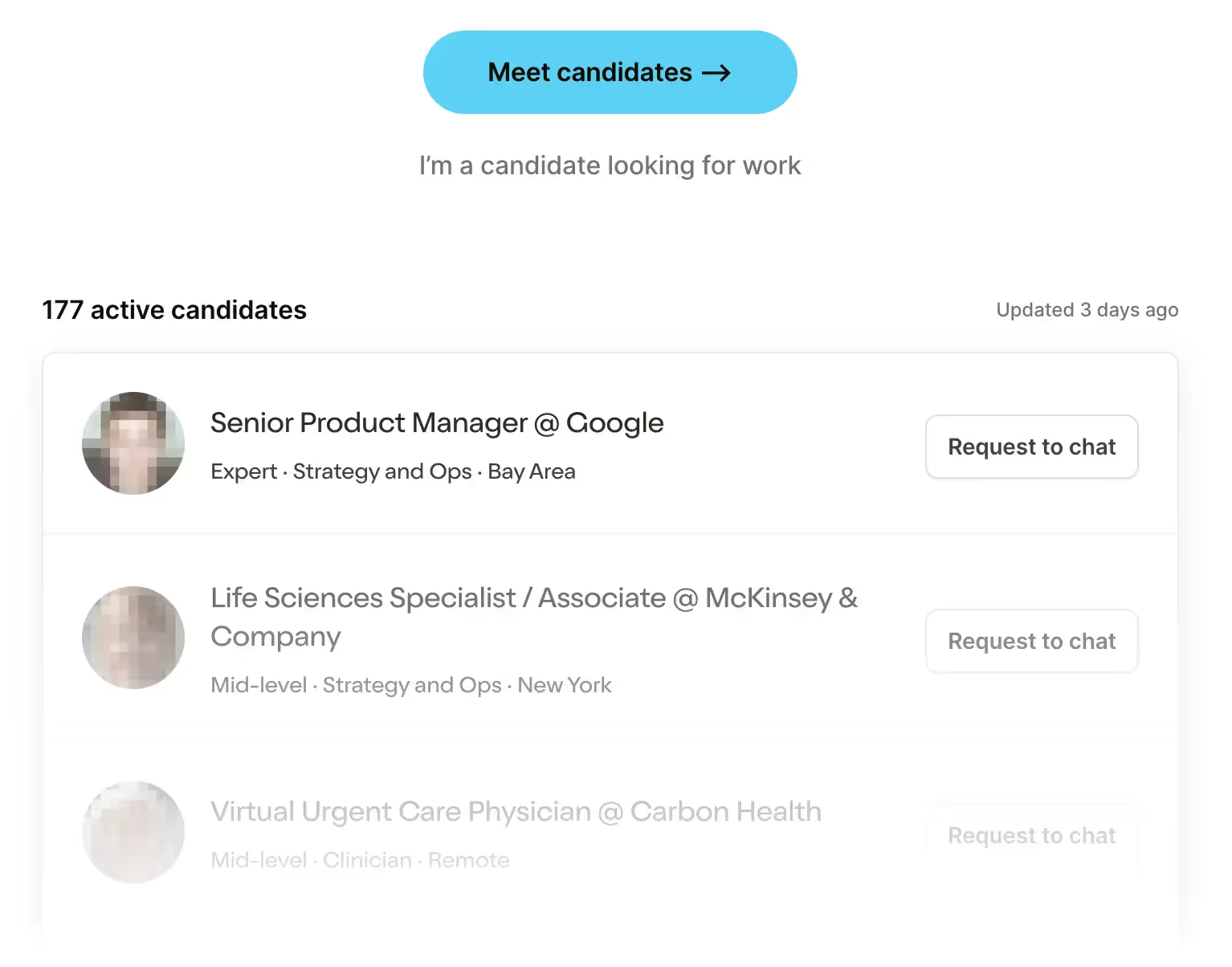

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveFeatured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Hospitals - the biggest (leaky) bucket of spend in healthcare

This is a guest post collaboration with Ben Chao, someone who knows a lot about how hospitals work. He wrote most of this, I just made it cute, added a little ~* flavor * ~, and asked basic accounting questions.

I groggily awaken, open my phone. First tweet says “US healthcare is 20% of GDP”.

I go to the gym. Hit the bench press, pump myself up listening to a Relentless Health Value podcast about specialty pharmacies. Hit a personal best right as they say “US Healthcare is 20% of GDP”.

I get my afternoon coffee and tell them the name for the order is Nikhil. They mishear and write “US healthcare is 20% of GDP, or about $4.3 trillion” on the cup.

Anyone in healthcare has heard this party line about US healthcare spend. But where does most of the money actually go?

The biggest chunk of spend is hospital care at 31%. And yet most health systems were lucky to generate over a 2% margin before the pandemic. In 2022, the median hospital operating margin was 0.2%. So it’s a big pot of money, but somehow there’s barely any leftover. These hospitals have to stop buying avocado toasts.

If we want to bring down US healthcare spend, figuring out how to do it at the hospital level is critical. But in order to do that we need to understand the basic physics of hospitals.

Today, we’ll dig deeper on health systems that have blended inpatient and outpatient settings, and understand what drives such large costs. We’ll go through each bucket of spend and some real-world examples in a spreadsheet.

General hospital expenses

A typical health system’s expenses are primarily driven by the following categories. We’ve kept it general here since health systems can categorize costs differently, and their spend by category can vary.

Let’s go through each of the major buckets of spend as a % of expense per year. At a high level we have:

- Salaries, Wages, Benefits (45-55%)

- Professional Services (12-22%)

- Supplies (12-18%)

- Depreciation/Amortization (3-6%)

- Other Expenses (5-20%)

Salaries, wages, and benefits of employees

Healthcare is a labor-intensive business, with salaries, wages, and benefits at 45-55% of a hospital’s expenses. Those appreciation day pizza parties really add up.

- Front-line staff like nurses, nursing assistants, medical assistants, and ancillary technicians dominate hospital full time employee counts. They generally represent 75-82% of the workforce.

- Non-clinical support staff, like folks in the call center, revenue cycle, information technology, marketing, legal, etc. generally represent 7-10% of the workforce.

- Health system management positions can range from 4-6% of all employees. These are the people everyone gets mad at.

- Employed physicians and advanced practice providers also count here. This can range from 4 to 9% depending on how easy it is to get them to join a hospital full time.

Front-line staff costs have jumped by 20-40% in the last 4 years amid an exodus of nurses and other front-line clinical support staff, forcing hospitals to resort to using contract labor from staffing firms. These staffing firms tend to charge 2-3x the hourly rate of an employed staff member, a rich premium for convenience and the guarantee of filling shifts.

A combination of lack of front-line labor and hospitals not wanting to pay up means that hospitals continue to suffer from understaffing challenges. This has led to labor battles nationwide for better increased wages, benefits, and safer staff-to-patient ratios.

How labor is divided between staff depends on the health system’s practice model. Some hospitals are revisiting their nursing ratios between a Registered Nurse and Nursing Technicians/Certified Nursing Assistants that support them. These two labor buckets have very different hourly costs.

Docs also have support models, with a clinic’s needs ranging from Registered Nurse support, 1-2 medical assistants supporting each physician, and a receptionist. Some clinics also have in-house referral coordinators and surgery schedulers as carved out roles, depending on the size of the practice.

Frontline staff aren’t the only salaries people have been talking about. Some health system executives who work for non-profit organizations have salaries over $10M a year, and I wish our college career counselor had mentioned this path at some point. This is controversial when comparing their pay as a ratio to an average employee’s pay. Health systems try to stay near median executive pay to avoid bad press, but I mean how could it not be bad press? Some states are either considering laws to cap pay or have laws to make executive pay more transparent.

An interesting dynamic that’s worth noting: non-profit health systems compete with for-profit hospital corporations on pay for talent, and non-profit employees can’t receive equity as a form of compensation. The only way to pay them is with cash, though a lot of it can be tied to performance incentives and deferred compensation. In every major non-profit health system, CEO pay is set by an independent board compensation committee, usually with support by outside counsel.

We’re not trying to defend the pay disparity (cancel Nikhil, leave Ben out of it). But it’s also hard to imagine someone who would work a 24/7 job, run a >$5B organization, and take less than $1M a year when their peers make at least 3x that - regardless of how much goodwill is in their heart.

Professional fees and purchased services

The next major category is professional fees and purchased services, ranging from 12-22% of expenses. This is the vaguest sounding category and was probably named by consultants, for consultants.

There are a few big buckets you might see here.

One is clinical professional services. Not every doctor you see at the hospital actually works there full time. Instead of a full-time employee, hospitals will contract with clinicians that work for a different company or private practice and work different shifts at a hospital. You’ll see this a lot in certain specialties like anesthesia, radiology, emergency care, neonatology, etc.

Depending on a hospital’s accounting practices, you might see outsourced nurse or other professional agency staffing costs show up here instead of in salaries/wages/benefits.

The second professional service is outsourced support services. Basically the back-office stuff like handling insurance billing, information technology staffing/consulting, courier services of specimens and disposables, health information management, physical security, parking services, recycling and waste management, etc.

Supplies

The third category of hospital expenses is supplies, typically between 12-18% of expenses. These are typically lower-cost/higher-volume medical devices or equipment, drugs hospitals keep on hand, laboratory supplies, personal protective equipment, linens, the 1 ply paper on the chair that’s doing a whole lot of work, intravenous solutions, etc.

Hospitals rely on global supply chains and have banded together to form Group Purchasing Organizations to negotiate the best possible prices. By force. Just kidding (we think).

Major equipment like an MRI or entire operating room suite might be funded separately via capital investment, which we’ll talk about now.

Depreciation and Amortization

Thus far, we’ve mostly talked about “operating expenditures” (aka. “opex”) which are typically expenses needed to run the place day-to-day. But what about those really big purchases like buildings, surgery machines, or the weird copier-fax-phone combo that gets used a lot for many years?

These are called “capital expenditures” (aka. “capex”). These typically don’t show up in an annual operating budget since they aren’t recurring and are very large. Depending on the size of the organization, they can easily be in the range of hundreds of millions of dollars per year, no cap.

But in order to try and account for those big purchases, hospitals will typically try to figure out how to spread out the costs for the big capital expenditures on a yearly basis. Are we starting to dredge up some tormented deep memories from Accounting 101? You might recall this as depreciation and amortization.

Depreciation and amortization is typically at 3-6% of expense per year. Both of these sound like made up words finance people came up with just so they could pretentiously emphasize the “DAH” in EBITDA.

How do health systems get large sums of upfront money to spend on capital projects? They typically sell hundreds of millions of dollars in bonds to banks and major institutional investors for these capital dollars. Most health systems have managed to stay financially solvent with massive cash/stock reserves and can live/die by their bond rating. The worse their bond rating, the higher their cost of capital, and the harder it becomes for them to operationally invest in new things or to maintain older buildings and equipment.

You can’t use this bond money for anything - it typically needs to be either strategic (e.g. creates net new capability for the health system) or for maintenance capital to keep the MRI machine sounding like a dubstep remix.

A few examples of capital purchases include:

- A hospital might pay for a new MRI or operating room with capital dollars and write down the purchase as depreciation for its useful life, reflecting as a multi-year expense.

- A hospital might buy a new building or make significant renovations. The cost of that building is amortized over its useful life and listed as annual depreciation, factoring for the cost of the capital to finance that purchase.

- A hospital might implement a major software platform that adds net new capabilities. Maybe they’re installing a next generation Enterprise Resource Planning platform or an EHR-integrated call center solution. Hospitals have used capital dollars to implement these major projects, especially if the combined project cost (licenses, labor, and added infrastructure) exceeds a ballpark threshold of ~$1M.

Other Expenses

A few other big expenses that are worth talking about.

- Software Licenses, Equipment, & Subscriptions: Every software company charges a damn annual license now. What happened to the good old days of buying a CD once and just booting it up. The big buckets of spend in this category are things like Electronic Healthcare Records, Enterprise Resource Planning, and Enterprise Data Warehouses, for example.

- Continuing Medical Education: Clinicians have to take accredited courses/conferences to keep their license that hospitals cover, but don’t ask why the conference is in Santa Barbara or exotic locations. This tends to be a recurring and relatively fixed expense that hits every year for providers. Each provider tends to have their own individual CME budget that gets tracked for reimbursement.

- Insurance: Types of insurance needed include medical malpractice and cybersecurity policies. These costs have risen in the last few years, particularly given the number of cyber/ransomware attacks on large systems.

- Leases & Occupancy Costs: Hospitals don’t necessarily own every building they operate out of, particularly in retail spaces for urgent or primary care clinics. These leases can in aggregate cost millions a year, not to mention office/admin/storage that hospitals may still use.

How does this breakdown vary depending on the type of hospital or health system?

At the end of the day, hospitals are still >80% fixed cost - you can’t really send the staff member home just because a hospital has less volume and you can’t unbuild a building, this isn’t Minecraft.

But there are a few differences between health systems where you’ll see variability in how they spend money.

1) For-profit vs. non-profit - For-profit hospitals tend to do a better job of keeping expenses/salaries lower than not-for-profit/government counterparts and generate a better operating margin. The trade-off is that for-profit hospitals typically don’t serve Medicaid beneficiaries, don’t provide charity care, don’t write-off bad debt, etc. Anecdotally the for-profit entities seem to be fine with cheaper and potentially older software vs. the “best in class”. An example might be using Meditech as the EHR (older and cheaper) vs. Epic for example.

2) The size of the health system - The larger the system, the more possible economies of scale in purchased services or supplies to negotiate better costs. There also may be economies of scale in salaries/wages/benefits. Merging hospitals might consolidate redundant or overlapping layers of management in operating departments, which is making a management consultant salivate just reading this. They might try the same in corporate support services like marketing, IT, and revenue cycle.

In an acquisition, the parent entity needs to actually eliminate jobs to realize some of its efficiencies. In some situations this can be a zero-sum game where over-cutting jobs can either degrade service quality or create switching costs (e.g the cost to migrate an acquired entity’s Electronic Health Record).

3) Local market dynamics and staffing - Local markets can also influence the competition for talent and labor availability. For example, it’s pretty hard to get people to work in small towns and country music as a concept isn’t helping.

Hospitals in rural areas have a smaller talent pool from which to draw from. Because of that, recruiting physicians who can bring high-margin cases or even adequately staffing a shift on a unit can be really hard. So the hospital typically needs to pay a premium by using outsourced services that send them clinicians and workers. This is typically at least 75-100% more per hour compared to employing them.

There are also state-level legal and clinical parameters that can influence staffing. For example, it would be clinically unsafe to have only one nurse managing any more than 6 patients at a time on a medical floor, especially if there’s no CNA/technician support. Several states are looking at bills that mandate a minimum nurse-to-patient staffing ratio.

4) Types of Services offered - Depending on what kinds of services you offer, you'll need certain types of staff and equipment. Bariatric and robotic surgery programs have >$1M equipment requirements, not every hospital has a cardiac catheterization suite, and different hospitals will have different units/floors for conditions like intensive care, psychiatric or memory loss care, acute physical rehabilitation, etc.

You can also see this as a compounding effect. Small hospitals tend to be less able to service significant debt and cannot afford to make large capital investments. That means they have less equipment to offer certain high margin services, which means patients end up leaking out of their community and going to more well-resourced facilities closer to population centers. Not being able to offer certain high margin services also means that physicians will be less likely to work for you - so now you have to pay extra to get talent.

Critical Access Hospitals are a good lens to look at this through. A Critical Access Hospital is a specific designation a hospital can get if it meets the following:

- Has 25 or fewer acute care inpatient beds

- Is located more than 35 miles from another hospital (exceptions may apply)

- Generally maintains an annual average length of stay of 96 hours or less for acute care patients

- Provides 24/7 emergency care

Meeting these needs means the hospital gets some extra reimbursement per discharge and for some of its support services, along with the ability to qualify for some other federal grant programs. But it also means carrying the disadvantages we mention above related to physician recruiting, raising capital, and making competitive investments to prevent patient leakage.

Financially sustainable Critical Access Hospitals tend to diversify beyond primary care, emergency care, and a single unit for medical/surgical cases. They’ll invest in things like home health, physical/ occupational/speech language therapy, and rotating visiting specialists (Orthopedic, ENT, and Sleep Medicine specialists who do visits 1-2x week and procedures 1-2x month in the community). They’re able to keep specialty care cases from leaking from their service areas.

But the reality is that most of these hospitals have basically no money, which means they can’t invest in any capital expenditure projects and labor keeps getting more expensive for them to get. Less money, mo’ problems.

A real life example of how this plays out

Let’s take a look at a few different health systems and hospitals with publicly-available financial data. A few disclaimers - neither of us claim to be forensic accountants and one of us didn’t know what a forensic accountant was. Data sources here are varied between public SEC filings, state-mandated Department of Health reports, and IRS Form 990s, so it’s tough to get true apples-to-apples data with deep detail. There could be a variety of reasons why each entity is performing the way it is. Factors like COVID impact operations and financial performance. Data availability and fiscal years are not uniform. Some of this analysis is purely speculative without an audit or talking directly to operators/finance leaders.

We’ll do a high-level apples-to-apples comparison across various entity types:

- For-profit - Community Health Systems

- Non-Profit Health System - Memorial Hermann

- Public Academic Medical Center - UW Medicine

- Large Rural Critical Access Hospital (public) - Pullman Regional Hospital

- Small Rural Critical Access Hospital (public) - Three Rivers Hospital

“Other Operating Expenses” here includes not just professional service fees (as defined above) but also can contain line items like licenses (enterprise software like EHRs and ERPs) insurance, training costs, utilities, interest, etc.

Link to the sheet here.

Here are a few noticeable things across these systems.

Salaries vs. Professional Services - There is often a relationship between salaries and purchased professional services.

- For instance, Community Health Systems (for-profit) appears to have the most efficiently run system in terms of managing salaries, until you compare it to Three Rivers.

- However, it’s likely that Three Rivers (small rural) – in its remote, river rich yet talent-thin location – must procure significant staffing agency support to keep its doors open, so some staffing costs show up as purchased services/other operating expenses, which is why it has the highest % of professional service fees among the group.

- Meanwhile, it’s likely that Pullman (large rural) has done a good job of keeping local talent around, hence a higher salary %. Guess it has quite a pull, man. Pullman has a diversified set of capabilities for a critical access hospital, with multiple subspecialties and decent procedural volume.

Rent and Leasing - There’s also a difference in rent and leases. Notice how the rural hospitals had a much lower percentage of their cost structure dedicated to leases when compared to the health systems in metro areas.

This reflects the differences in business models between a critical sole community provider with a few outpatient locations and a system that relies on patient acquisition through dozens of primary/specialty care clinics in retail locations. In competitive markets, hospitals need more locations to have touchpoints with patients. Outpatient locations need to be far enough from hospitals and from each other to reach more patients, but close enough that a patient might actually go stay within their system for a downstream surgery or ancillary service.

COVID Effects - Let’s go further back in time with Memorial Hermann Health System, the largest non-profit health system in southeast Texas. Their system of 6,600+ affiliated physicians and 33,000+ employees across over 260 locations (17 hospitals) has grown steadily over the last four years, from $5.4B in revenue in 2019 to $7.3B in 2022.

A few reflections from their financials:

- Thanks to the detail provided in their Form 990s, we can see how Information Technology costs have hovered around $30M/year, which doesn’t include any IT staff or contractors. That’s a tiny portion of their net revenues at around 0.5%.some text

- Hospitals spend less on technology than you might hope. This is why health tech companies eventually add some of those sweet sweet services since the budget for headcount and professional services is bigger.

- We also see a slight rollback - close to 10% from ‘19-’21 - before a bounceback in 2022. That’s likely due to budget cuts and an ask of vendors to suspend some contracts while the system tried to stabilize as COVID hit.

- More on COVID: From March to June of 2020 the industry saw a broad suspension of service/clunky transition to virtual. some text

- As a response, health system managers enacted furloughs and layoffs - look at the 2.6% drop in salaries in ‘21.

- They also suspended renewals and leases to the extent they could (leases dropped slightly from ‘20 to ‘21).

- Finally, they tried to migrate as many of their primary and medical specialty appointments as possible to virtual. That might have put a dent in some revenues on a per-facility basis. Why were there increases in year-over-year revenue, then? It’s most likely due to acquisition/partnerships of other practices or organic growth from hiring new physicians.

- Based on this chart, one could argue Memorial Hermann has financially recovered from COVID-related impacts or even come out with better performance as a result, with their net operating income moving into double digits while their cost structure looks relatively similar to what it did before COVID.

Conclusion and some parting thoughts

Whenever the American Hospital Association makes an announcement, it’s usually meant to be a tearjerker about how hospitals constantly lose money. But…should our tears be jerked?

On the whole, the largest health systems in America seem to be recovering financially from COVID, even as staffing shortages continue. The staffing/agency market has settled into a more sustainable place than where it was a year ago. The system’s ability to manage employment vs staffing costs seems has a big impact their financial sustainability.

An analysis by the consulting firm Kaufman Hall of ~1,300 hospitals tells a story:

- Hospital emergency department visits: returned to pre-2020 volumes

- Average length of stay: decreased (more patients coming through the doors)

- Outpatient visit and surgery volumes: increasing, driving profitability

- We are: So Back.

But the gap between different hospital types seems to be getting wider. The median hospital is running at a 3.8% operating margin, while the bottom quartile threshold is at -2.6%. Blake Madden at Hospitalogy recently put together a good comparison. Health systems generally are seeing better results with the for-profit companies leading the way. Rural hospitals are, as our Gen Z friends say, “cooked”.

Hospitals with worsening margins will likely need to change things up. That means shifting to different revenue models, seeing how much they can get from insurers, or totally changing the cost structure of the hospital. In future parts of this series, we’ll explore how they make money and how they might make those changes.

Thinkboi and Thinkben out,

Nikhil aka “Underdepreciated” and Ben Chao aka “Ben in hospital P&Ls a little too long”

Twitter: @nikillinit

IG: @outofpockethealth

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

--

{{sub-form}}

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

Interlude - Courses!!!

See All Courses →We have many courses currently enrolling. As always, hit us up for group deals or custom stuff or just to talk cause we’re all lonely on this big blue planet.