Physicians and Pharma Marketing

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

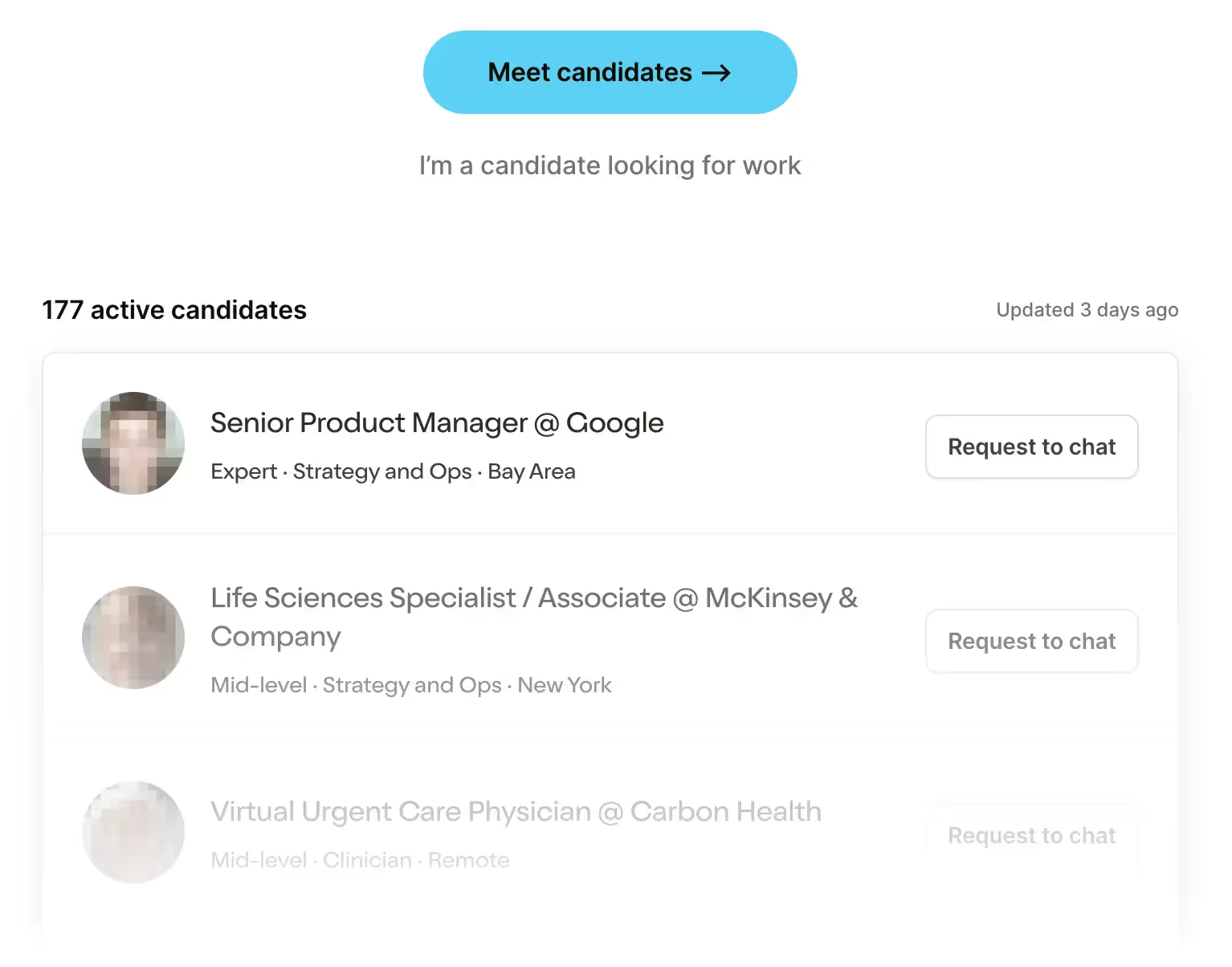

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveFeatured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

“Wow what a normal number of pens laying around this doctor’s office with the names of pharmaceutical products. Time to see my unbiased physician who will write me a prescription.”

In 2008 pharma’s lobbying group, the startup-y named PhRMA, put out its own code of conduct around interacting with physicians which agreed to stop giving physicians schwag. My guess is that this was more likely self-preservation - pens are an easy way for patients to physically see that their physicians have a relationship with pharma companies.

Actually it was so important to highlight no schwag, that after 17 pages of talking about nearly every single interaction pharma-physicians have, the first 2 questions in the Q&A are “can we offer stethoscopes?” and “can we give physicians clipboards if they’re attached to informational material?”. If you close your eyes and imagine this conversation between an annoying 4th grader and a hungover teacher, it’s almost a perfect match.

Previously I talked about pharma direct-to-consumer advertising. We went through the reasons they advertise to consumers, the different types of ads, how marketing to consumers is changing, and I argued that maybe direct-to-consumer ads are actually not that bad. This is partially because it’s pretty clear that you’re being advertised to.

Today I want to talk about pharma advertising to physicians, which is a bit different because it happens more behind the scenes. The goal of advertising to physicians is pretty obvious - they want physicians to write more prescriptions of their product. But there are lots of different ways they advertise, directly and indirectly.

But I’ll also say that I don’t think we should completely ban pharma-physician interactions for reasons I’ll explain later in the piece. Instead we should think about how to make it more productive and transparent.

Background and Context

Before I get into this, there are a few key pieces of background information that are worth keeping in mind.

- Pre-2010s, breakthrough drugs were found in diseases that affected a lot of people, could be largely prescribed in primary care settings, and were small molecule drugs that didn’t have a ton of storage requirements. Think cholesterol drugs, asthma meds, etc. However, in the last decade or so, a lot of those initial blockbuster drugs have become generic and are not the pharma money makers they once were.

- Pharma is much more heavily focusing on complex biologic drugs that have specific storage needs, can get expedited approval by targeting a rare disease with an unmet need (cancer, genetic disorders, etc.), and where the approved drug targets a mechanism of action that can be used to treat a lot of diseases with the same drug. This is especially important as many of these drugs will get approved quickly targeting one disease, but physicians can prescribe it for any disease they want (which is called off-label prescribing). Physicians will do this if they believe the overlapping diseases have a common mechanism of action and the patient's current treatment isn’t working. For example, Humira got approved for rheumatoid arthritis in 2002, but was prescribed off-label for many other diseases and received approval for many other diseases later. Having data from off-label outcomes is very helpful when it comes to knowing which diseases to run a formal trial on next.

- We’re also slowly inching towards drugs that are given once or a handful of times and actually cure the disease (e.g. Hepatitis C drugs, gene therapies, etc.). Considering most of the pharma value chain is built with the assumption of volume-based sales, the shift to curative therapies will shake up alot of how sales and marketing work.

- Information is becoming much more accessible to everyone. While physicians can more easily look things up online, there is also too much information available and new information about drugs coming out constantly.

- Pharma companies also have access to the types of patients a given provider sees and prescription and medical claims data to understand the prescribing patterns of different physicians. Apparently access to prescribing practices is required because of...the First Amendment and free speech?

- In part due to the opioid crisis there has been a much higher level of scrutiny and reassessment of the relationship between pharmaceutical sales and physicians. What was once a semi-”behind closed doors” relationship has been deservingly thrust into the spotlight. If you haven’t watched the “Crime of the Century” documentary, it walks through a lot of the craziness that used to happen between pharma and physicians.

Put together, these trends have forced a metamorphosis of the pharma sales force from a door-to-door knocking relationship game to a highly targeted and complex marketing + sale. At the end of the day though, there are several things influencing a physician’s decision making around medications that most patients probably aren’t totally privy to.

Let’s talk about some of them.

Pharma Sales Reps, Detailing, and Drug Samples

Pharma sales reps do a lot of face-to-face visits with doctors, understand the patients they’re seeing, make doctors aware of new drugs that have been approved, and inform them of changes to recommendations in how drugs should be administered. This is called detailing.

The purpose of these visits was theoretically to inform and educate about a solution to a problem docs were having, which is basically what all sales & marketing is. But doctors are very busy, so there needs to be some reason for them to listen. Sometimes you’ll pay for their time, sometimes you’ll make the educational venue more attractive (like a dinner or event). Sometimes that line gets crossed and it’s clearly not educational, as outlined in this suit against Salix Pharmaceutical.

“Many of these doc-in-the-box programs were little more than a mechanism to provide the attendees with extravagant dinners and an opportunity to socialize, and the speaker with $250 per event for doing little to nothing. Sales representatives often would not play the pre-recorded programs. And if the programs were played, the laptop or other device on which they were played was placed in a location where it could not be seen or at a volume at which it could not be heard.

...A doctor from Providence, Rhode Island, was the paid speaker for numerous events during the Covered Period, earning more than $190,000 in honoraria. For approximately half of these events, the medical discussion lasted 15 minutes or less, including multiple events that were entirely social in nature with no medical discussion. The events were primarily a get together for the attendees, who in many instances knew each other and even practiced together. On multiple occasions, the sales representative announced that the attendees could just have dinner.”

If you’ve ever talked to anyone in the industry, they will tell you how insane some of these events used to be in the ancient times (like 20+ years ago). They always will add the very careful qualification of “I didn’t really go to them, but I heard that…”.

Pharma sales reps would also frequently give physicians samples of new drugs. Seems like a win for everyone - physicians get free samples to see how they work before prescribing, patients get access to free medication, and pharma companies get to distribute a product they think works. Samples were a great way for pharma reps to actually get a foot in the door with the doctor, who would need to meet face-to-face to sign off for them. Samples are so important that pharma sales reps actually have detailing bags that are designed to hold lots of samples and brochures, and they’re very recognizable in a hospital.

Isn’t it a little weird how the samples are always branded, more expensive, and don’t have cost-effectiveness studies done against similar drugs that might be marginally less effective but a fraction of the cost? As my parents say, “there’s no such thing as free” and “I don’t understand the cartoons in your newsletter”. Free samples are very slowly becoming less tenable now that a lot of the new branded drugs coming out are not shelf-stable pills that doctors can just keep in their drawers.

When thinking about detailing, free samples, etc. it’s important to understand the incentives for pharma sales reps. They largely get okay base salaries but most of their take home money comes from commissions. This is usually some combination of outreach, total prescriptions written, total $ worth of prescriptions written, and other volume-based metrics within their sales territory. Thanks to prescription data from companies like IQVIA, monitoring this has become doable.

This was one of the big issues during the opioid crisis - many sales reps had uncapped commissions and would push physicians to increase the dosages if patients weren’t responding (with the constant message that “it wouldn’t get patients addicted”). In some cases, you make corporate rap videos to pump up your sales team to sell the highest dose of a fentanyl spray. Sometimes that video is played for a jury figuring out whether to sentence you for physician kickback schemes. The incentive misalignment here between sales and patients added fuel to the already raging fire.

Today there is definitely more scrutiny into the sales rep <> physician relationship. Access to physicians is getting harder every year, especially in hospital settings where an increasing number of physicians work.

Plus as drug pipelines focus more on specialties like oncology vs. older blockbusters that focused on primary care settings, the number of physicians that sales reps need to interface with is just much lower (there are 12K oncologists in the US vs ~294K primary care clinicians).

Add this all together and the role of the pharma sales rep seems slowly getting outdated. In 2005, there were 102K pharma sales reps vs. 63K in 2014. Feels like the role and compensation of the rep needs an overhaul, not just saying “we’re not going back to the old way” despite keeping the same incentive model that ended up with the old way.

Medical Science Liaisons

In the last few years there’s been a growth in the role of Medical Science Liaison (MSL) with the MSL to sales rep ratio increasing over time.

MSLs are people with scientific backgrounds (pharmacy, pharmacology, physicians, clinicians, etc.) that pharma hires to be “peer educators” for physicians. They generally have higher levels of accessibility to healthcare practitioners than sales reps. Here’s a job description for one and a pretty clear outline of how they interact with other teams. The general gist is that MSLs:

- Find and identify important people in a given specialty and maintain relationships with these key opinion leaders (KOLs). Sometimes this starts as early as when a doc is in fellowship!

- Answer questions that physicians might have about different drugs, results from a trial, etc. Nowadays drugs are getting approved faster, the drugs themselves are more complicated, and the approvals are coming with lots of asterisks. Physicians can’t realistically keep up with all the information coming at them, so having a scientist to answer their questions is useful.

- Help physicians design trials for drugs that might already have an approved use case, but the physician might want to study it for something else (different disease area, a combination with other interventions, etc.). This might take the form of an investigator initiated study, where the physician/institution handles all the operations and takes on the risk while the drug company provides the drug. Or it could be a formal Phase IV trial where the pharma company is evaluating real-world efficacy of an approved drug (which we’ve talked about before).

An interesting quirk of MSLs is that they technically cannot bring up off-label uses unless the physician explicitly asks about it. But by having the role of the MSL which has knowledge and research of how a drug is being used off-label, a physician pretty much knows that it’s something they should ask about. This is especially true because it can lead to these physicians getting paid to run Phase IV trials or think about their own research they might want to pursue, which is...sort of like paid marketing to physicians?

Talking to a sales rep now feels weird and taboo, but talking to a peer that HAPPENS to work for a pharma company? Well, that’s just learning right?

MSLs feel like the evolution of sales in direct response to drugs getting more biologically complicated and more stuff happening with the drug after it’s approved. Sure, MSLs are explicitly “non-promotional”, but that’s all in the eye of the beholder and patients should probably understand how this relationship might impact their care.

Consulting Fees and Speaking Fees

Physicians will get speaking fees by pharma companies to talk about the benefits of the drug, their findings from prescribing it in their practice, etc. This is meant to facilitate peer-to-peer discussion between current and potential prescribers.

In many cases, pharma companies will ask physicians already prescribing the drug to give a talk. Sales 101 is to get an existing customer to talk to a new one. Many physicians might internally rationalize it as not changing their prescribing behavior since they were already prescribing. But it makes switching away from that drug later tougher if that’s now an income stream, and it creates a perverse incentive in the community where physicians might start prescribing a drug knowing colleagues have gotten lucrative speaking engagements as a result (from what I hear, this was much more egregious in the ancient times).

Physicians will also get paid consulting fees by pharma for things like helping design protocols for clinical trials, making suggestions on drug development itself based on their real-world experience using the drug off-label, answering market research questions, etc.

In order to make this more public, the Physician Payments Sunshine Act requires medical manufacturers to disclose to CMS if they make payments to physicians. There’s an open database tool where you can look up how much any physician is receiving (ProPublica has a more searchable version). The variance is quite high, some people out here getting $25M+ in a given year through payments, other people out here getting one lackluster Sweetgreen salad reimbursed.

I will note there is some nuance to this data. This money might go to fund research where the physician is the lead investigator instead of directly in their pockets for example. But directionally you can see which physicians interact with industry, the frequency in which they interact, and the magnitude of dollars at stake. In fact, anecdotally I know that companies will use this data as a proxy to understand which physicians are already open to working with industry players.

The database was intended to make physicians think a bit harder when taking industry money knowing it was going to be public. The result? Total payment value went down slightly, the total number of physicians receiving payments went down slightly...but the mean and median amount actually went up! The people getting very small amounts decreased and the people getting very large amounts decreased, but the people in the middle actually started getting more.

There’s also some critique that the money usually going to physicians is now just going to other areas of influence that are less reported, like paying patient advocacy groups, for example.

So it might not have had the magnitude they were expecting, but I think it’s good that this information is public. Maybe the issue is just that patient’s don’t know it exists. If you saw your doctor, could visibly see who they receive payments from, would you be more likely to ask/be skeptical of the doc if they prescribe a medication from that company? Honestly in most cases there are very reasonable explanations and most patients probably wouldn’t care if the total amount of dollars is small. But if your physician is getting paid $10M+ from industry? I’d probably like to know that.

Sponsored Continuing Medical Education Courses and Conferences

The entirety of biotech and pharma runs on conferences. Companies will wait to publish their results on nearly unreadable and poorly formatted slides at the big conferences like ASCO, ESMO, etc. These conferences are also where lots of physicians attend, especially in fields where research and treatment are very intimately linked (oncology, neurology, etc.). Pharma has a heavy presence in these conferences when it comes to sponsorships, advertising, number of people on the floor, etc. These have become such important events for sales and marketing that entire companies have been built and acquired that focus on analytics around conferences + meetings.

This isn’t just general industry conferences, but it’s also true for medical education conferences where physicians are keeping their skills sharp. Physicians have to get Continued Medical Education (CME) credits to keep their license or stay credentialed (depending on the state + hospital). These credits come from places that help physicians stay up to date on things changing in their field (and have to be CME approved).

Conferences love to get that CME certification to generate demand. Doctors love going to CME conferences in nice locations (in many cases it’s a tax writeoff). And pharma loves sponsoring CME conferences since a lot of physicians go to them. In 2017, about 28% of total dollars to accredited CME providers came from industry (pharma, med device, etc.).

This gets tricky because although CME conferences claim to have firewalls separating the agenda from the actual sponsors, in practicality I wonder how much that’s actually followed.

Does pharma marketing impact physician behavior?

Compared to consumer advertising, I find physician advertising to be much more dicey because it happens behind the scenes with way less accountability than direct-to-consumer advertising.

The impact has also been studied countless times in several different meta-analyses. Physicians generally tend to prescribe a given drug from a pharma company after having some sort of interaction or payment from that company. Many of them establish the relationship as causal and actually show temporally how the prescription patterns change from their baseline post-payment. Yes there’s definitely a pattern of higher dollars paid yielding more prescriptions of a drug, but even small meals still have an impact.

Frankly one of the ways you know it works is because pharma maintains a high level of spend towards physicians. Actually there are entire swaths of consulting firms that help figure out how many touch points with a physician gets them to actually use a new drug or yield X% of prescription increases. Here’s one of the more thorough papers examining this topic:

"The researchers estimated that for every additional dollar spent on detailing visits, drug firms could expect to reap $2.64 in increased drug revenue over the next year – a 164% return on investment. Previous estimates were much higher, ranging from 200% to 1,700%, according to the study.”

Pharma and physicians should have a more transparent relationship

Despite outlining all of the ways that physicians are marketed to and also seeing plenty of evidence suggesting that it does impact physician prescribing, I don’t think there should be a complete moratorium between pharma and physicians.

For one, you want practicing physicians to be involved in helping to design different therapies and clinical trials because they have a better understanding of how it can help patients. And you want pharma to keep physicians up to date on the latest research in the field. Information flows between the two entities should exist and are valuable IMO. Investigator- initiated trials, Phase IV trials, and understanding how drugs perform in the real world especially requires an open-channel between the two that by necessity will require a financial relationship. Who would pay for the trial otherwise?

It’s easy to quantify “after the meal, prescriptions went up” because the datasets are very easily available (which is good), but it’s way harder to quantify “this drug got approved because consulting physicians helped design a better trial”. We should, however, probably do more analyses on things like “did patients change to X drug, a more appropriate treatment, after their physician got lunch from that pharma company?” because then we can surmise if it was a net positive interaction for the patient as well. That’s a much harder analysis to do though and requires more types of data.

A parallel piece is that physicians are constantly pulled in a million different directions, and if they didn’t get any sort of monetary incentive they likely wouldn’t take part in it since there are places they can allocate their time to more directly get compensated. I think the issue is when physicians can get compensated so much from industry that it becomes secondary to actually practicing. But if you believe it’s important for physicians to time interfacing with pharma in some capacity, then getting paid for that time seems reasonable and probably a necessity.

Instead I think we should do a few things. For one it probably makes sense to cap the total amount of payments a physician can receive from pharma. Maybe it’s a % of salary or some form of tiering so that the highest demand doctors still see it as worth their time but have to be more selective about who they choose to work with. Sure physicians should be incentivized but they shouldn’t aim to make that their main revenue source.

I also think patients should have more transparency into this. Could appointment scheduling companies include this as a part of the filters? Maybe I’ll see if there’s a chrome extension to be built that connects to the Open Payments database and brings up the amount your physician has received in industry payments while you’re on a telemedicine call with them. Hmmmmm…

But I think at the core of it, most of the problems with physician marketing stem from a broader problem of physicians having almost no financial incentive to deliver cost-effective outcomes to patients or having any sort of exposure to the cost of these drugs or a patient’s out-of-pocket expenses. If physicians got paid to deliver the best outcomes relative to the cost inputs, then choosing new and expensive branded drugs would not always benefit them financially. But with no tie, then there’s way more room for bias if they have financial ties to one of the potential options for medications. In fact, many physicians are actually incentivized to give higher cost drugs anyway through buy-and-bill practices, where they get the drug’s Average Sales Price (ASP) + ~6%.

Instead of trying to suddenly police physicians, we just need to fight personal financial incentive with personal financial incentive and make it more attractive for physicians to give cost-effective drugs vs. the hot new thing the pharma sales rep is peddling. I think the reality is that it will be impossible to truly police these things because there is a never ending number of ways that pharma can pay physicians that will get harder to monitor (e.g. I’ve heard some unconfirmed stories that online publications that are fully funded by pharma will pay physician contributors quite a bit to write thought leadership pieces for example). Do we really want to set up another admin arms race between pharma and the regulators to monitor this?

There’s also some inroads to potentially moving pharma to a value-based reimbursement model for their drugs, but that’s much more likely to apply to their new, extremely expensive drugs vs. any incentives to potentially use older cost-effective ones. So I’m not going to get my hopes up there.

I’d be curious to hear others' thoughts. Is it possible to have a healthy relationship between pharma and physicians, and what do you think that looks like? Or should we just ban money flowing between the two completely?

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. "interest of conflict"

Twitter: @nikillinit

P.S. I guess it’s a long running trope that pharma reps are very attractive. You can see the introduction of the pharma sales rep characters in Scrubs, New Girl, and How I Met Your Mother if you want to see a caricatured portrait of a pharma sales rep.

Thanks to Chris Hogg and Neelesh Mittal for reading drafts of this post

Interlude - Courses!!!

See All Courses →We have many courses currently enrolling. As always, hit us up for group deals or custom stuff or just to talk cause we’re all lonely on this big blue planet.