Radiology, Residency, and Physician Tools with Henry Li

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveIntro to Revenue Cycle Management: Fundamentals for Digital Health

Network Effects: Interoperability 101

.gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Today I’m interviewing Henry Li, currently a radiology resident at Stanford and a co-founder of Reify Health.

We discuss:

- Simple tools that would help physicians and low-hanging fruit tech can play a role in helping

- What a radiologist does and where AI will shake things up

- How residents are graded + thoughts on how to change med school

- Interpersonal dynamics within the hospital and changes in hospital process post-COVID

1) What's your background, current role, and the latest cool healthcare project you worked on?

My background: I studied biomedical engineering as an undergrad, with a focus on bioinformatics. I then studied health informatics for a master's degree, working on clinical decision support tools and public health tools as well as cost-effectiveness research for cancer diagnostic tests. Then a medical degree. I spent my intern year at a large cancer hospital (Memorial Sloan Kettering) and am currently on my second (out of four) years as a radiology resident at Stanford.

Early on in medical school I took leave for 3 years to co-found a company, Reify Health. We started off building a platform for text message–based clinical research and care. A lot of researchers and doctors had great ideas on how they might induce behavior change or collect data using text messages or other mobile health tools, but lacked the technical chops to do it. We were able to help a ton of projects do some really creative stuff — appointment reminders and high-frequency surveys, sure, but also some automated, super-customized message campaigns which adjusted texting algorithms and/or content based on text responses. We also could pipe in data from things like Fitbit and... Fitbug? (There wasn't too much else back then.) This was circa 2012, so many of our customers' projects were angled to this weird emerging idea of "digital health therapies" or "digital therapeutics" — sign up a patient for a robo-SMS weight loss program and compared to normal weight loss clinic, they lost more weight!

There were clinical trials, studies, academic centers, self-insured employers... anyways, fast forward, and we had lived through your famous stages of health tech grief, and eventually pivoted to focus on the mechanics of clinical trials. This came about because at first we were wondering if we could shoehorn mobile health and at-home diagnostics into trials to drag them into the future (can't)... but we eventually landed on building software & tools for accelerating clinical trial enrollment and startup, which is a more concrete (and lucrative) problem space. As you probably know very well from your time at TrialSpark, a lot of the challenges & opportunities with clinical trials aren't in the realm of "does this treatment affect this clinical outcome" and more in the operations and processes and inefficiencies around finding patients, starting sites, training people, monitoring performance.

After 3 years I left to return to medical school, and now I'm interested in the myriad ways new technologies can interface with radiology and clinical care as a whole.

2) You've mentioned the low-hanging fruit opportunity for simple tools that can be built to help physicians. Can you give a couple of examples?

Over a Zoom get-together recently with a bunch of former classmates (now residents, fellows, attendings, etc) we were discussing how much of our day-to-day work in the hospital, especially as an intern or resident, required a medical degree. Several people immediately said, "0%". The highest we got was "25%". The main reason? There's just so much menial computer & phone related labor to do.

One example is getting medical records from other hospitals. While we wait for vendors to agree (or be forced by government decree) to implement some semblance of interoperability or data-sharing portals or APIs or whatever, we're still over here calling the patient's last hospital, the medical records department phone # which we found on Google, faxing forms back and forth, and then sitting there combing through piles of printouts of meaningless documentation to find a few crucial pieces. I think there might be ways of co-opting the fax workflow, kind of like Doximity does with their fax #, but adding some pieces like OCR or NLP summarization to make life easier.

Another area is in things similar to MDCalc and other "decision support tools" (in a broad sense of the term). For example, doctors are notoriously bad at interpreting test results and sensitivities/specificities, and a lot of diagnostic workup is centered on dogmatic teaching rather than data. Providers could use quick tools to help think through diagnostic problems for different pathologies, pros/cons of tests to order, and intuitive interpretations of likelihood ratios & odds ratios. I think there's opportunity to shift thinking to be more data & probability driven, which is more adaptable overall, especially to changing conditions (new tests/treatments coming out, new diseases, shifting prevalences).

3) Can you walk me through the process of a radiologist looking at a scan? Where does it come from, what's your process, where do you write notes, how does communication happen between parties, etc.?

For most cross-sectional studies (e.g. CT, MRI, PET) before we even get any images a radiologist (or a radiology technician) will generally review the imaging order and the indication. We want to make sure it's appropriate. The clinician may have ordered a certain scan when another is better for some reason (less radiation or faster or cheaper or more sensitive or more specific). Or maybe we don't think any imaging will change the clinical management. We'll often get in touch with them (preferably by phone) to talk through these tradeoffs and to make our recommendations. We also need to select the right parameters and settings for the scan. A doctor may order "brain MRI", but we have to then make a range of different choices regarding which MRI sequences to run, which anatomical parts to focus on, which reconstructions and post-processing steps are needed, all based on what the doctor is looking for (ruling out a stroke? following up cancer metastases? working up a weird headache?).

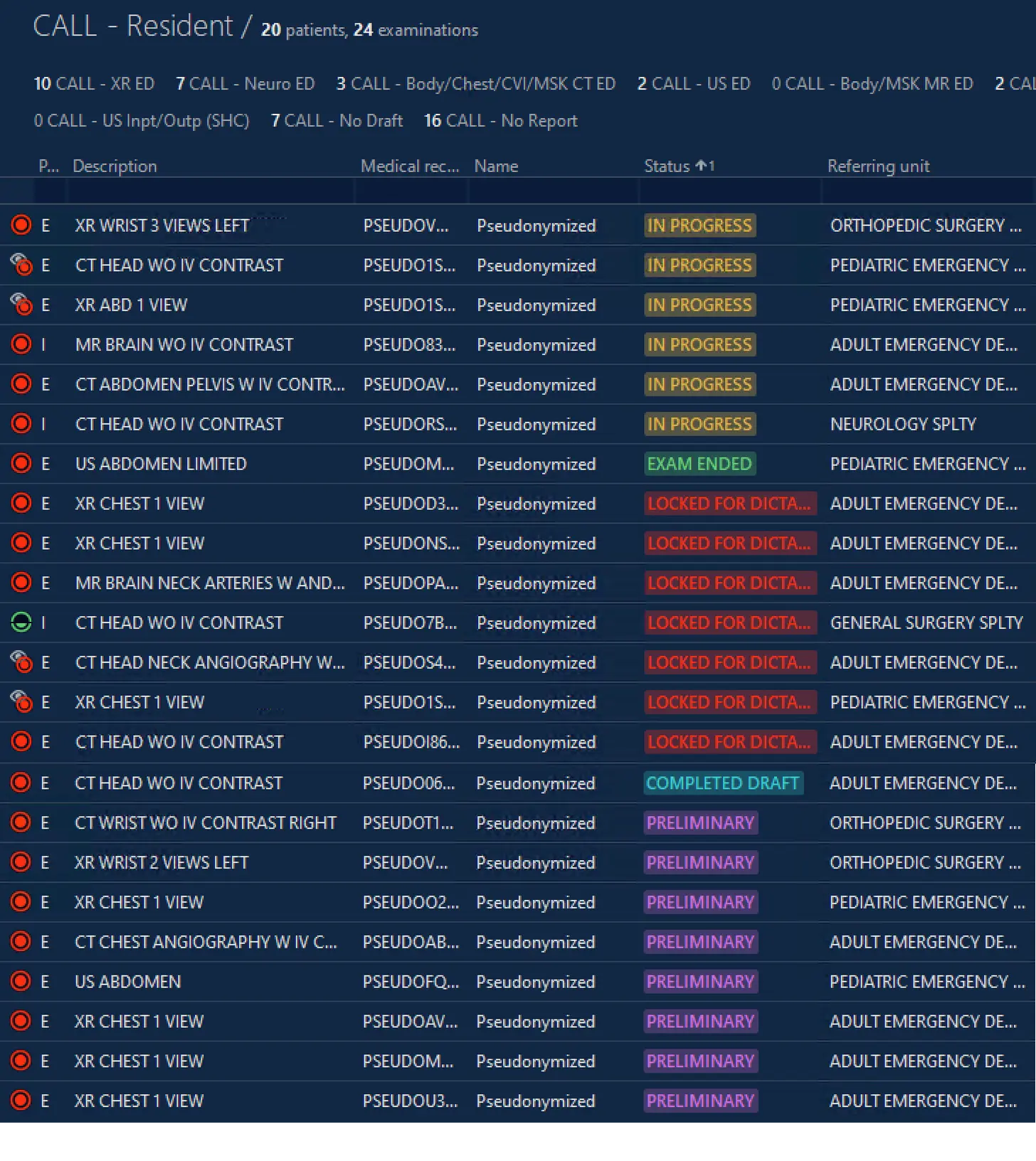

The radiology technicians and nurses then do the actual work of getting the scan done: positioning, making sure the images are satisfactory, etc. Images come to us through the PACS (picture archiving and communication system) usually as part of a worklist, which is our queue of exams to review.

For each, we see what clinical history we have. Ideally the clinician who ordered the exam will have written us a succinct yet informative line about why the exam was ordered. For example, for a CT of the head it might say "history of migraines but with sudden onset of the worst headache of his life". For another CT it might say "high speed motor vehicle accident". Each clues us into the reasoning for the study and can help us frame our review and our report.

In reviewing images, we generally follow "search patterns" that we've been taught or developed over our training and practice. These patterns make sure we're methodical, thorough, and consistent — kind of like a mental checklist. We usually dictate the report as we go, and often the templates in the dictation software are structured to help with these patterns. Nevertheless, there is a significant amount of subjectivity, especially with more complex or rare findings.

The PACS also lets us make measurements and annotations on the images. For example, on a CT scan following up cancer treatment, we may measure the size of each questionable tumor or lymph node. On a scan of the head after a car accident, we may draw arrows pointing out subtle fractures in the skull. These measurements and annotations are visible by radiologists (maybe a radiologist reading a future scan who wants to assess change over time) and by clinicians.

We create the report in the dictation software, which then gets associated with the images in PACS and pushed into the EMR. (The dominant software for dictating reports seems to be Nuance PowerScribe, which has remarkably accurate voice recognition when paired with their dictaphone.) The report distills the images, the patient's clinical history, and the radiologist's opinionated interpretation into a text document. It gives room for nuance and persuasion, and allows some explanation & justification.

Frequently, we may reach out to the clinicians to discuss emergent findings, usually via paging/phone. Sometimes they may call us or come visit us to go over the images, especially when things are complex, subtle, or equivocal. We also often reach out about findings which, while not emergent, are really important. For example, we might call to recommend further work-up of a mass at the top of the lung that was incidentally seen at the end of a scan of the head & neck — the mass isn't an emergency, but we want to be damn sure the doctor knows about it. It's remarkable how often the report isn't read, or isn't read fully, or things get lost in transitions of care, etc.

4) There's been a long debate around AI replacing doctors and radiology always comes up as one of the first examples. You've mentioned in the past that you're bullish on radiology practices that are "AI-native" or have it incorporated into the workflows from the beginning. Where do you think AI will actually be useful in radiology? Do you think the speciality is going to change in 10 years vs. how it looks today?

Oof. Lots of much smarter people out there have probably much smarter thoughts on this than me. But here's my quick take.

AI replacing radiologists comes up very often among experts and laypeople for two reasons, I feel. One is that computer vision is an AI task that most people are familiar with and comes to mind quickly when thinking about AI — self-driving cars, facial recognition, that hot dog app in Silicon Valley, etc. The other is that many people trivialize the task of radiologists and think that it is just a computer vision–based classification problem: input some images, output some diagnosis labels (pneumonia, pancreatic cancer, stroke, normal).

And I think this is interesting because as a result, we're probably overestimating and underestimating the potential of AI at the same time. We're probably overestimating how rapidly we can get diagnostic AI in terms of acceptable accuracy and reliability. But we're also underestimating how much AI will impact all sorts of other aspects of radiology workflow outside of the diagnosis part. I mentioned some of the steps of the imaging lifecycle, many of which could probably be dramatically improved with AI, whether it's protocoling studies, triaging your worklist, summarizing patient histories, measuring/annotating metastases (seriously such a pain for us), generating/improving reports, identifying similar images from other patients, suggesting next steps in diagnostic workflow or management, etc. There's also work on algorithms to improve image processing and acquisition for decreasing radiation dose in CTs and increasing speed of MRI scans.

One of the prominent Stanford radiologists who has been working/writing in AI and such, Curt Langlotz, has this great quote which has been pretty widely circulated: AI won't replace radiologists, but "radiologists who use AI will replace radiologists who don't." At some point we will probably no longer be comfortable with a human reading our CT scans, and instead we will insist on or require a human who uses state-of-the-art tools. So I think there's an opportunity now to start training radiologists with this in mind, and to build radiology practices which are tech-centric and which continuously iterate on the tools and workflows to improve efficiency, accuracy, and utility to the referring clinicians. And if you could demonstrably show that you were stronger/better/faster — again, probably doable even without the whole AI-doing-the-diagnosing part — you could begin to argue this point, which is that people should come to you for radiology interpretation rather than the human-only yokels elsewhere.

One interesting example of AI improving workflow would be with triaging studies — identifying urgent ones that probably need attention sooner, something Nines Radiology has gotten FDA clearance for.

5) As a resident, what are you allowed to do vs. not allowed to do vs. an attending? What does your schedule look like? How are residents "graded"?

Residents vs attendings: As a resident, one of the only things we are not allowed to do is to "final sign" a report. A final report drops the image off the "to be read" worklist, and the report gets sent into the EMR and to the ordering provider (and sometimes to the patient). The final report is usually locked and can no longer be modified (though you may add an addendum/correction — which can be quite embarrassing when you have to write something like "Addendum: on review, the tumor is in the LEFT lung, not the RIGHT"). The final report assigns the legal responsibility to the signer and, of course, allows for billing.

As residents progress, they can also issue "preliminary" reports. Like final reports, these also get sent into the EMR and to the clinicians — though with a "prelim" status. This status is generally understood to mean, "This is probably right but a more experienced person (AKA an attending) will review it and there may be changes." You can imagine how this can be kind of challenging, especially if the prelim report says "no stroke" and the patient gets sent home, but the final report later says "yes stroke". Overnight is when things like this can occur, as that's when there's just residents in the hospital and the attendings don't come in until morning. While this may seem like a major flaw in the system, there is a strong argument to be made that this sort of gradated unsupervised decision-making is a major component of training — and it happens to various degrees in other specialties in a training hospital as well.

(During the day, residents create "draft" reports which are reviewed in real-time with the attending. The attending will use that opportunity to point out missed items, correct things in the draft, and to teach about various topics related to the imaging at hand. These corrected reports then becomes prelims as they wait to be signed by the attending.)

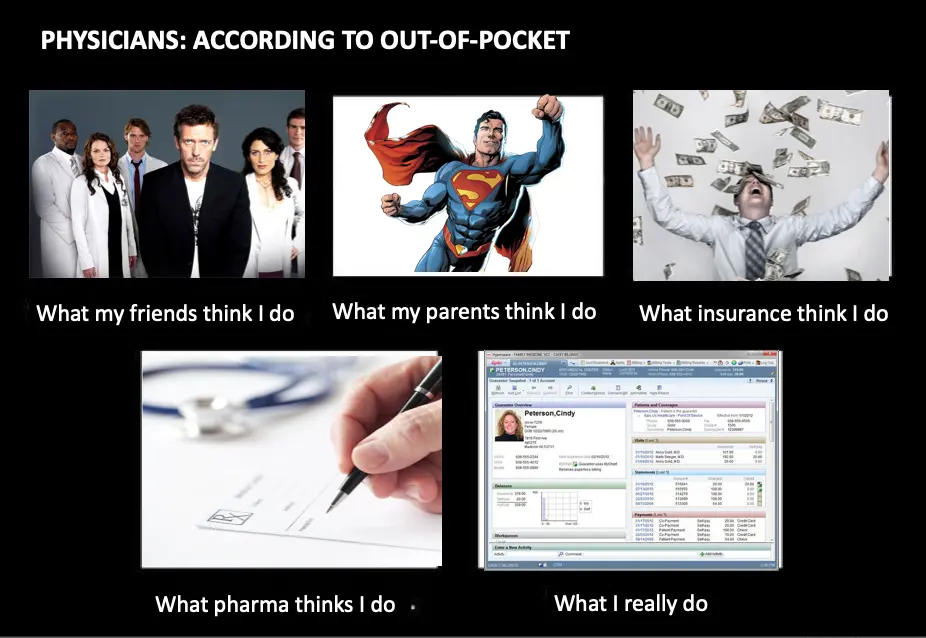

Schedule: We rotate through the various subspecialties in radiology, usually a few weeks per block. On diagnostic rotations, our schedules in general are fairly civilized as compared to our colleagues in medicine or surgery — it's usually 7am-5pm, Monday-Friday. (The head of radiology where I went to school shared with me this meme when I was thinking of applying into radiology.)

We do have scattered weekend shifts and spend several weeks to months each year working overnight and such (often shifts with hours like 5pm-2am or 8pm-8am).

And when we rotate on things like interventional radiology (which is a subspecialty closer to surgical/procedural fields, responsible for a range of things including complex cancer treatments, emergent hemorrhage control, etc), the schedule becomes a bit more aggressive — I've been on it the past month and have been starting around 6:30am every day, finishing around 6pm or so, though occasionally much later (2am once). There's overnight call once or twice a week, and more weekend responsibilities, as we are actually the primary team for our inpatients and outpatients. I definitely ran into the 80 hour work week limit.

Grading: How residents are "graded" is a fantastic question. I would say "not well and not much", and this applies broadly to probably all residents across all specialties. Nobody graduates "top of their residency class" — or "bottom", for that matter.

The outcome of interest for residents (and residency programs) is fellowship acceptance or job offers, and that's mainly based on things like research or connections or recommendations from faculty/leadership. Good recommendations likely depend on you being a good resident, but there's not really any grading.

While you do get evaluated by attendings you work with, these are online forms with a bunch of Likert scales and a couple of free text fields, and they are about as useful as you would imagine. Mercifully, unlike in medical school, these evaluations don't become a grade and have little bearing on anything. You can read them at your leisure (or not), though your residency program is required by the ACGME (the body that accredits residencies) to have a session with you to go over your performance twice a year.

You may also take "in-service" exams annually, which are standardized multiple choice tests to roughly gauge your aptitude against others at your training level. These also are not of major consequence; if you do poorly, you may be given a slap on the wrist and told to study harder, for example.

Other than that, I mean, you could be a really great resident or a really crappy resident, and that's just how it goes. Then you graduate and you're off to practice somewhere. (Sure, if you were really really crappy, you could get fired from residency/fellowship, but you'd have to be causing egregious harm or having super significant issues working with others — getting fired is a big deal and not easy.)

Radiology residency does have some aspects which lend to more quantitative measures for self-assessment. For example, you can look at how many studies you complete per shift compared to others at various levels of training. You can also look at how frequently your prelim reports get changed and to what degree, to see whether your independent decisions overnight were correct. Things like that.

As an aside, I think medical education and evaluation is overall a significantly underserved area in terms of tech, whether it's before, during, or after residency. Whether it's high fidelity simulations, or access to decision-support, or aggregating institutional knowledge from the EMR... And just the concept of high-stakes infrequent multiple choice examinations is ridiculous — I've been tuned into a fantastic multiple choice question answerer, but that has no bearing on my proficiency as a clinician.

6) Let's say tomorrow you woke up as the dean of the top med school. What're your first 3 orders to change the med school process (cost/financing structure? curriculum? grading?)

1. Make it tuition free. Several (e.g. NYU, Wash U) are already tuition free or are on the way there. Even half or part tuition would be a step. Clearly it's not a simple switch you can just flip, but I feel that it's a huge and powerful move in improving access & diversity. It also would allow students to place a little less weight on future income when considering specialties — a hard enough decision already. Reminds me of this great interview with the dean of NYU, and when asked where med student tuition used to go: "It supports unproductive faculty."

2. Try to decrease curricular emphasis on fact memorization, which is of course much easier said than done. Unfortunately a lot of the big tests (especially Step 1) are geared toward fact memorization. I remember a question from Step 1 which boiled down to choosing which chromosome held the gene responsible for neurofibromatosis type 1, a rare genetic disorder. What possible circumstance would I have to be in to need to know this fact? Like, somewhere somehow I encounter a patient with this obscure disease and then need to run some genetic analysis AND THEN ALSO don't have access to Google?

Meanwhile, there's a lot of research which shows that doctors are tragically abysmal at thinking through basic statistics around test results. Like, "your mammogram is positive, what is the likelihood you have cancer" type basic test results... many studies have shown the majority of doctors get this type of thing wrong (and not by a little — by a lot). (e.g. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/1861033)

It's easy to teach (and to memorize) facts and associations and diagnostic if-this-then-that pathways, but these become calcified in your head over time and that stuff is fragile. We discover new diseases, new treatments, new diagnostic modalities. The "whats" of medicine change but the fundamental "hows" remain.

(By the way, the gene responsible for neurofibromatosis type 1 is obviously on chromosome 17, which you can recall because the disease is also known as "von Recklinghausen disease" and that eponym has 17 letters and yes I will carry that fact to my grave)

Another curricular gap is in conflict resolution, team management, that sort of thing. Doctors work closely with a lot of people with different levels of training, different task goals, different personalities. But they don't get taught how to be effective at working together, or how to resolve problems, how to make sure teams are effective.

More in this vein: top academic med schools have a lot of academics who love to do research, which does not necessarily correlate with being good at clinical medicine or being good at teaching medical students. They often teach what they are researching. So I guess part of my mandates would be around hiring people who are actually invested in teaching and incentivized to teach.

This med school better have a hella big endowment...

3. My last item is semi-related, and is to think of creative ways to shorten the duration of medical school. Nearly all US med schools are four year programs... but they probably don't have to be. NYU has a 3 year accelerated track. McMaster in Canada is 3 years. Med schools in other countries are often 6 years combined with undergraduate schooling. The timing with residency application & match cycle in the U.S. is tough, but there is a lot of cruft in the first 1-2 "pre-clinical" years which you could cut out or replace. (Did I really need to memorize that neurofibromatosis fact?) You can increase your emphasis on those other things I mentioned in the last point, with the remaining time, and probably produce as good (or better) future physicians.

7) There are lots of support staff at hospitals (scribes, nurses, physician assistants, etc.). How do you interact with them? Where are they most helpful/when does tension exist between you and any of these groups?

It's definitely variable; many of the staff perform tasks which a physician would (or could) never do. Others have a lot of task overlap. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners, for example, sometimes operate in roles which are similar/identical to physicians. As such, interactions are sometimes working side by side and sometimes more hierarchical. Many times things are very transactional, and large number of interactions occur through the medium of the EMR — orders being sent to nurses, documents being written as a means of communication.

Of course, as with any group of people working closely together under pressure with distinct and challenging roles, there is often tension. Sometimes that's the nature of the work: the patient is coding and the nurse can't reach the doctor; the team asked the social worker to do something which he then forgot about, delaying discharge, etc. Situations are hard and people aren't perfect. Often you want things to be more collaborative, but the structure of things means that the doctor is the ultimate decision-maker and arbiter, even for small, seemingly silly things, and the dynamic is hard to get out of.

Still, a lot of times the tension seems artificial and unnecessary. Going back to my point about a lack of training around team & conflict management — often things get blown out of proportion by personalities and egos (often by & between doctors). Often one party gets obsessed with how wrong/dumb/inept another party is and can't seem to let that go, to the detriment of relationships and patient care.

Some aspects of successful teams in the hospital I've noticed:

- Roles are clearly established, yet members are willing to step outside of them to help get things done

- Understanding of individual limitations and reaching out for help

- Proactive in raising concerns

- Receptive to hearing concerns

This probably isn't really any groundbreaking team dynamic revelation, and there are people out there who have dedicated their careers to researching and implementing these and other concepts in the healthcare workplace. But it is alarming how rare it can be to see in the hospital.

8) In a post-COVID world, what have been the most noticeable shifts at the hospital? What do you think is here to stay?

Many things which were formerly considered rather urgent suddenly are being delayed. Cancer screenings and surgeries are being rescheduled for further out. Even procedures/imaging in the emergency room wait for COVID test results. (Thankfully, the rapid tests generally return within an hour or two, though not always.) Some of it makes sense, and some healthcare was probably very delayable, but some bits feel more like "health security theater", and we ended up making really weird risk calculations.

I think one of the more lasting things will probably be more robust surge & disaster planning, preparedness in general. Most institutions have plans for how to handle, like, mass casualty events (bombs, mass shooting, etc), but they were rarely tested and generally didn't account for the prolonged and widespread waves that COVID has brought to hard-hit spots. But now many places have had to make some plans for equipment, staffing, facilities. And the hospitals that haven't been stressed yet have had the chance to plan and to think through strategies.

I also think more clinic visits will persist as telemedicine visits. I've only conducted a few, and they certainly have their benefits and their challenges. But I think patients (and providers) generally appreciate the added option, and now the idea has rapidly been at least somewhat normalized. COVID is also going to be around for a good bit in the US, and so these tele visits will get to enjoy more time in this forced "trial" period.

Bonus: As both an engineer and a doctor, what are you parents disappointed about now?

Oh boy. After college when I started on my master's degree, my mom would repeatedly remind me that I wouldn't have a "real" degree, and that I should get a PhD or maybe do law school or medical school. Then, after starting medical school, she kept harping on how to really be successful, you needed your own company. Of course, once I told her I was leaving medical school to start a company, she freaked out about my unfinished medical degree. Even now with me in the middle of residency, she'll still needle me about her friends whose kids are lawyers and how much money they make. I just nod and smile.

I do have to give her credit, though: when I was a kid and obsessed with video games, she implemented a rule where I had to study programming and could only play games for as much time as I had spent learning to program each day. At some point I started enjoying the programming as much as (or more than) the games. So prescient. So tiger mom.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “mom please don’t read Henry’s resume”

Twitter: @nikillinit

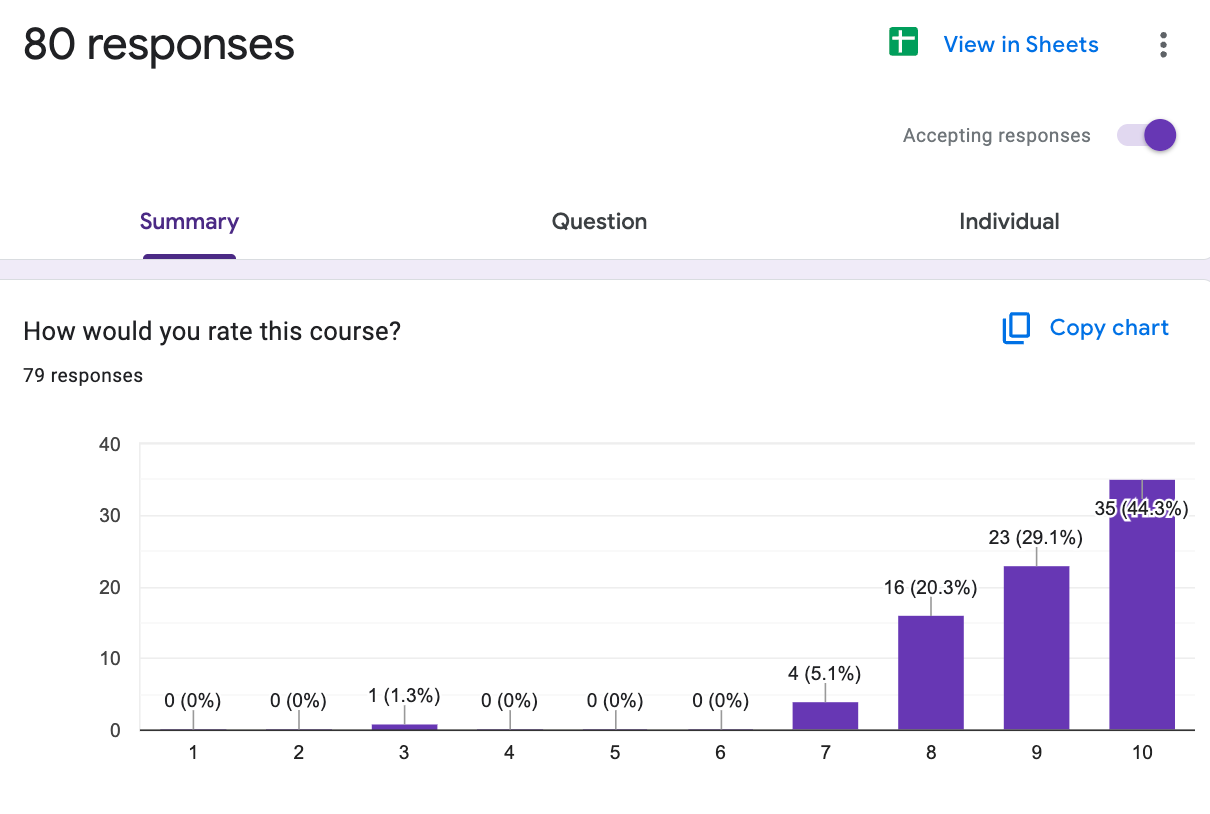

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!!

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

Selling to Health Systems (starts 10/6) - Hopefully this post explained the perils of selling point solutions to hospitals. We’ll teach you how to sell to hospitals the right way.

EHR Data 101 (starts 10/14) - Hands on, practical introduction to working with data from electronic health record (EHR) systems, analyzing it, speaking caringly to it, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →Our Healthcare 101 Learning Summit is in NY 1/29 - 1/30. If you or your team needs to get up to speed on healthcare quickly, you should come to this. We'll teach you everything you need to know about the different players in healthcare, how they make money, rules they need to abide by, etc.

Sign up closes on 1/21!!!

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.