Research papers and the patient perspective

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveNetwork Effects: Interoperability 101

.gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Paper life

It’s been a while since I’ve done a post about papers I’ve liked. That’s partially because I no longer have the attention span or basic literacy to read papers. I need to be literally locked on a flight with no wifi and the HBO app once again fucks up downloading episodes to watch offline (it has one job?).

Luckily, that exact scenario happened recently. As I read through a few of these papers I wondered to myself if this is what academics have to do all day. I found a tear was rolling down my cheek almost by instinct. I also noticed that there was a thread across the papers I was reading - they all showed slightly different sides of how patients experience the healthcare system.

Below are three papers I liked, some thoughts on them, and why I think they’re a good lens to view the patient journey through.

Do doctors understand insurance design?

Here’s a paper that looked at whether physicians, if given a patient’s health insurance information, understood how much the patient would pay out-of-pocket for that drug. There is so much to say about this paper I don’t even know where to start.

First of all, let’s look at the methods. They sent doctors an envelope with…$5 lmao. But even better is that the letter said to fill out this survey otherwise…mail back the $5…

- You know med school debt is crippling if $5 is worth their time. 400+ docs responded! 45% response rate on a MAILED survey for doctors is insanely good.

- The estimate of 8 minutes to finish the survey is like when recipes tell you the total cook time will be 20 minutes but assume you’re a trained chef that preps materials in 60 seconds.

- Who is opening this letter, reading it, seeing the money, then putting it back in the envelope? I feel like this is secretly a trap by an ethics committee or something.

Now, the fun part. The docs take this survey where they’re asked whether or not they’re obligated by duty to help patients lower their out-of-pocket spend and then whether they’re able to.

After that, they’re given a vignette about a patient where they need to guess how much a patient would pay if you prescribed a $1,000 drug using the patient’s insurance information they have readily available (already a fantasy scenario).

This feels like the doctor version of “Johnny buys 50 watermelons” math problems

The results present an interesting story.

- 3/4ths of docs think they have an obligation to help patients keep their out-of-pocket costs low, but most also don’t feel like they know how to do that or have the time to do that. I’m happy to give a suggestion: simply don’t send me a bill 🙂

- Just over half of docs even understood how the deductible worked. A surprising chunk said she’d owe $500, presumably because they think the 50% coinsurance kicks in before you hit the deductible. You’ll be displeased to know that insurance won’t give you one goddamn cent until you hit your deductible (*except for some preventive care visits).

- Primary care docs seemed to do better with questions about deductibles and copays, and specialists seemed to do better at out-of-pocket maximums. That sort of makes sense considering the kinds of patients both groups see - you’re more likely to be interacting with a deductible if you’re seeing a primary care doc early in your care journey and you’re more likely to blow through your out-of-pocket max if you’re dealing with a specialist.

This leaves me with a few takeaways.

The first is that insurance plan designs are f***ing nuts. Doctors at a baseline are pretty educated people, and only half understand how deductibles work? How are regular patients supposed to understand this stuff?

Sometimes I think a lot of the issues with the healthcare system is a mismatch in expectations - you have no idea what you’re buying until suddenly you need to use the healthcare system a lot. Maybe we’d see people less upset with the healthcare system if it didn’t feel like they were duped.

The second is that it opens the question of whether doctors are the best financial stewards for patients, especially at a time where we seem to be pushing more providers to take on financial risk. Honestly, when it comes to reading insurance, doctors are just like me fr fr. And I’m not even sure we should be demanding that doctors know everything about how insurance works - I’d rather them spend that marginal hour learning about new developments in their field or how google calendar works vs. learning how to navigate insurance design.

It would’ve been interesting for this survey to ask the doc if they’d switch the patient to a different drug now knowing that out-of-pocket cost burden to a patient. How would care plans change in response to coverage?

Finally, this feels like a layup for software. Right now, it’s still impossible to actually get information about plan design and how much of your deductible you’ve hit while you’re sitting with your doctor. As a stopgap, I wonder if you can potentially stitch this story together in the patient intake form by asking a patient to give access to their claims history /explanations of benefits via companies like Flexpa, then ask a few follow-up questions. Then when you’re with the doc, they’ll know how much things they order will cost you.

But I already know some hospitals will use this to find patients that have hit their out-of-pocket max for the year and order like 3 MRIs with contrast for no reason.

The Oregon Medicaid experiment - winning the very low stakes lottery

If healthcare ever made a canon of must-reads, the Oregon Medicaid experiment would be on it. Every single person that’s ever vaguely taken a healthcare economic or policy course will claim these papers are God’s gift to the field and the mere mention of it is effectively foreplay.

Let me explain why people love this paper. In 2008, Oregon expanded Medicaid to way more people in the state. Narrator: “that was a hard year to make that choice”. Because they didn’t have the funds to do it for everyone at once, they held a lottery for the 90,000 people eligible for Medicaid and gave 30,000 the ability to sign up. It was like a loot box but for the social safety net. Of those selected, 17,962 (61%) submitted applications, and 8,704 (30%) were approved for coverage (source)**.

This is the kind of natural experiment health economists would commit war crimes to simulate. Everyone enrolled at nearly the same time, it had a fat N, and it was a real-world randomization (**big caveat above). All of these together makes it much easier to ask the question, “how does getting Medicaid coverage change healthcare for this patient?”. And for the last 15+ years, new papers have come out tracking patients in this cohort, which you can see here.

Three big papers came out a few years after this experiment, and here are the things they found at a high level.

- Having Medicaid increased healthcare utilization across the board. People with Medicaid were going to more outpatient care, getting more prescription drugs, and had an increase in hospital admissions and emergency room visits. This is estimated to have increased spend by $1,172 per person compared to the control group.

- People on Medicaid didn’t really show improvements in most of the standard health measures - cholesterol, blood pressure, cardiovascular risk broadly, diabetes measures, etc. Interesting and important caveats are pretty significant improvements in mental health and self-reported feelings of overall health. Critics say that the papers didn’t look over a long enough period of time, and later papers did show that the Medicaid group had reduced maternal mortality + positive health outcomes for children. The findings here still seem up for debate.

- Medicaid significantly reduced the risk of large out-of-pocket medical expenditures, catastrophic bills, or medical debt. The number of people that had to borrow money or skip payments dropped by more than 50%!!

- Medicaid had no real impact on employment and earnings, private health insurance coverage, or even whether people turned out to vote.

As you can imagine - these papers became a litmus test for political ideologies. Those who believe Medicaid is welfare wrote about the extra taxpayer money spent on these recipients without their health actually improving. Those who believe Medicaid is good point to the increased utilization of preventive care services, reduction in financial hardship, and mental health improvements.

But this is where actually hearing from patients directly matters a lot IMO. From a great interview with someone who received Medicaid through the lottery:

Q: If you hadn’t won the Medicaid lottery, where do you think you’d be financially and medically?

A: Financially, I’d be maybe $100 a month poorer. I would not be monitoring my blood sugar. I would not be paying as much attention to my cholesterol. I probably would have lost some weight but I don’t think I would have lost so much, and I don’t know if I would have been so good at keeping it off. I’d be much more anxious about what could go wrong….

And there’s something about just feeling like you’re part of regular life. There’s a lot of emphasis on how everyone should be healthy and everyone should live longer, and you don’t want to be a burden on society. If you don’t have medical insurance, you’re kind of not part of that. It’s hard to explain, but there’s an element of participating in society that being able to go to the doctor gives you.

Everybody always asks everyone how you’re doing, and to be able to say “My doctor says I’m doing really well,” that’s nice, instead of being in a group of people and saying, “Well, I don’t really go to doctors.”

The improved depression score and self-reported improvements capture some of this, but misses the nuance. Asking someone whether their health is good can never accurately portray the feeling of peace of mind and how that helps them feel at ease in society. Now we can debate whether or not we should be paying $1,100+ per person for that peace of mind, whether that should come with strings attached, etc. But at its core, that’s something that can’t be captured in claims data, just like any other useful information (j/k take the claims course, please).

The reason I like this series of papers is because they force us to ask the question…what’s the point of Medicaid exactly? Is it to improve the health of people on it? Is it to provide financial safety to the most destitute? Is it to help people become contributing members of society? Is it to purposely confuse people with Medicare? Is it to keep people happy?

There’s no consensus answer here, which is why the request for proposals from every state are different when they’re looking for a health insurance carrier to administer their Medicaid program. But talking to individual people helps add some color to the total impact that these programs can have for people.

Neutropenic diets that don’t taste like ass

When someone is immunocompromised as a side effect of something like chemo, it’s somewhat common to tell them to eat a “neutropenic diet”. This means no raw, unpasteurized, or cured foods to reduce the possibility of bacteria and infections that might overwhelm your body (in case one of your tone deaf friends is sending a “get well” charcuterie board). Hospitals will also generally prevent any outside food from coming in that they can’t verify is neutropenic, in case one of your tongue deaf family members gets you Arby’s.

However…there are issues with neutropenic diets.

- There isn’t really any research that suggests neutropenic diets actually avoid infections. It seems like in the 1960s-1970s, there were a lot of cancer deaths post-chemo from infections, so neutropenic diets became a part of the post-chemo regimen. At the time, hospital kitchens seemed to have had the hygiene standards of a frat house during rush week and lots of infections came out of it; so maybe there was some merit?

- Cancer recovery is pretty miserable and malnutrition is a pretty big issue with the recovery process. Wouldn’t it be great if patients could eat the things they wanted?

- Soft cheese slaps. And hospitals overcook the food to the point you wonder if they’re catered by Applebee’s.

In the last couple of decades, several papers have come out talking about how neutropenic diets are probably not actually helpful and already several hospitals have basically stopped the practice.

But it’s still a pretty pervasive belief. It’s hard to get a sense for how many hospitals tell patients they should stick to a neutropenic diet, but here’s a few interviews with a handful of clinical staff and over 50% told their patients to go neutropenic. However, most of them didn’t even agree on what the definition of neutropenic meant.

Why does all this matter? Well I thought this quote from one of the doctors AGAINST the neutropenic diet in those interviews was interesting (edited for clarity):

“I feel like it gets twisted. We want you to eat everything that’s processed. We want you to eat canned vegetables rather than the fresh fruits and vegetables that are probably soaked in salt. It just feels counterproductive. It’s harmful when my patients are undergoing taste changes, or they really don’t want to eat. And the only thing they want to eat is what we’re telling them not to eat, like a salad.

So, I think it’s more harmful in that it decreases the options available to this patient population that already has so many dietary issues, like a decreased taste, appetite, mouth sores, etc.. There are a lot of battles we’re already fighting, and I don’t want this to be one of them.”

Which brings us to today. Recently, a paper was presented that studied the effect of neutropenic diets on bone marrow transplant patients. It was prospective, randomized, multi-center, and was pretty well powered at 200+ people, with a patient makeup that was pretty similar in both arms.

Pretty simply - they gave one group the protective diet that didn’t have raw foods and cooked everything to over 80oC (that’s 176oF…that temp will turn chicken into a diamond). The other group was up to hospital hygiene standards and excluded raw meat/fish.

I thought maybe the reason past neutropenic studies had small samples was because no one wanted to risk the downside of getting infected. But this study author said:

"We said to them, you have a 50-50 probability of being free of this diet if you enroll in this trial,” Stella said. “Then they would be like, ‘OK, wonderful.’”

This is the most literal “I’d rather die than eat this” you’ll ever see.

The study found essentially no increase in GI infections, length of hospital stay, etc. Incidences of fever, sepsis, and GI infections were basically the same as you’d find at a local Chipotle. But most importantly, patient satisfaction was much higher in the non-restrictive diet by a large margin. 16% of patients receiving the protective diet vs. 35% of non-restrictive diet patients reported "diet did not negatively impact my alimentation", a word I may have had to Google. I mean only 1/3rd of people saying the food wasn’t bad still feels super low…but it’s a start.

The reason I liked this study was because it really wasn’t looking at anything other than improving the patient experience. How many studies have the sole purpose of doing that? There’s always a lot of talk around how patients are noncompliant with the treatment plans they’re given. But how many studies look at trying to simplify complex regimens and REMOVE things patients need to do? There’s just really no incentive to.

There are a lot of things that doctors will suggest just because it’s been common practice. But I think any practice is worth revisiting to see if it’s still worthwhile.

I think we should be doing more low-lift studies like this to see where we can increase the patient experience. Even if the study found a marginally higher rate of infection for non-neutropenic diets, we’d at least be armed with data to present to patients and let them risk it all for Sweetgreen if they really want to.

The harvest bowl will have the best testimonial it’s ever received.

Some parting thoughts

Each of these papers looks at a slightly different slice of how a patient experiences the healthcare system. What you end up finding is a seemingly neverendless set of complicated and random rules that patients struggle to make sense of, with their opinion frequently disregarded.

A few other things I noticed about these papers:

- Usually it’s hard to run experiments in healthcare when it comes to changing an intervention (e.g. giving a new drug, testing a new device, etc.). You need to convince patients, take a long time to study the effects, enroll large samples to get the statistical power, etc. But virtually every part of the patient experience can be A/B tested quickly (consent forms, call center scripts, messaging, etc.) and it feels like we should do that more.

- Most studies FEEL like they were designed by economists, researchers at health systems, doctors, etc. Everything from the hypothesis being tested to the survey questions asked. I’d be interested in seeing what patient experience studies designed by other patients look like. Maybe they could vote on studies they’d want to see done lol. Organizations like PCORI work on things like this + a bunch of new tools for patient reported outcomes that could probably enable this.

- It’s pretty easy to find studies that show the opposite conclusion of most of these studies, so you can’t really make too many generalizations on just a single study. This is most clear with the Oregon Medicaid papers, where different ways of slicing the data will show what you want to find, especially when there’s political motivation.

I used to be a big believer that we should trust the quantitative data and people would weaponize individual patient stories to further their own agenda. I think I’m swinging to the other side now, and think that in a lot of ways we’ve become over reliant on that quantitative data in decision making. Quantitative data can never capture certain things about the human experience in healthcare, and sometimes doing more qualitative analyses is necessary.

For that reason and many others around the incentives of publishing, academic journals do not like qualitative studies. A few people told me that when they submitted papers they also had the qualitative interviews as a supplement and were told to take them out. Journals have an obsession with accuracy and demonstrating causality, but papers might feel more approachable to regular people if there was some storytelling or patient stories too.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka “Paper boy, paper boy, reading all the papers boy”

Twitter: @nikillinit

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

Thanks to Bea Capistrant, Lindsay Zimmerman, and Jon Palisoc for reading drafts of this

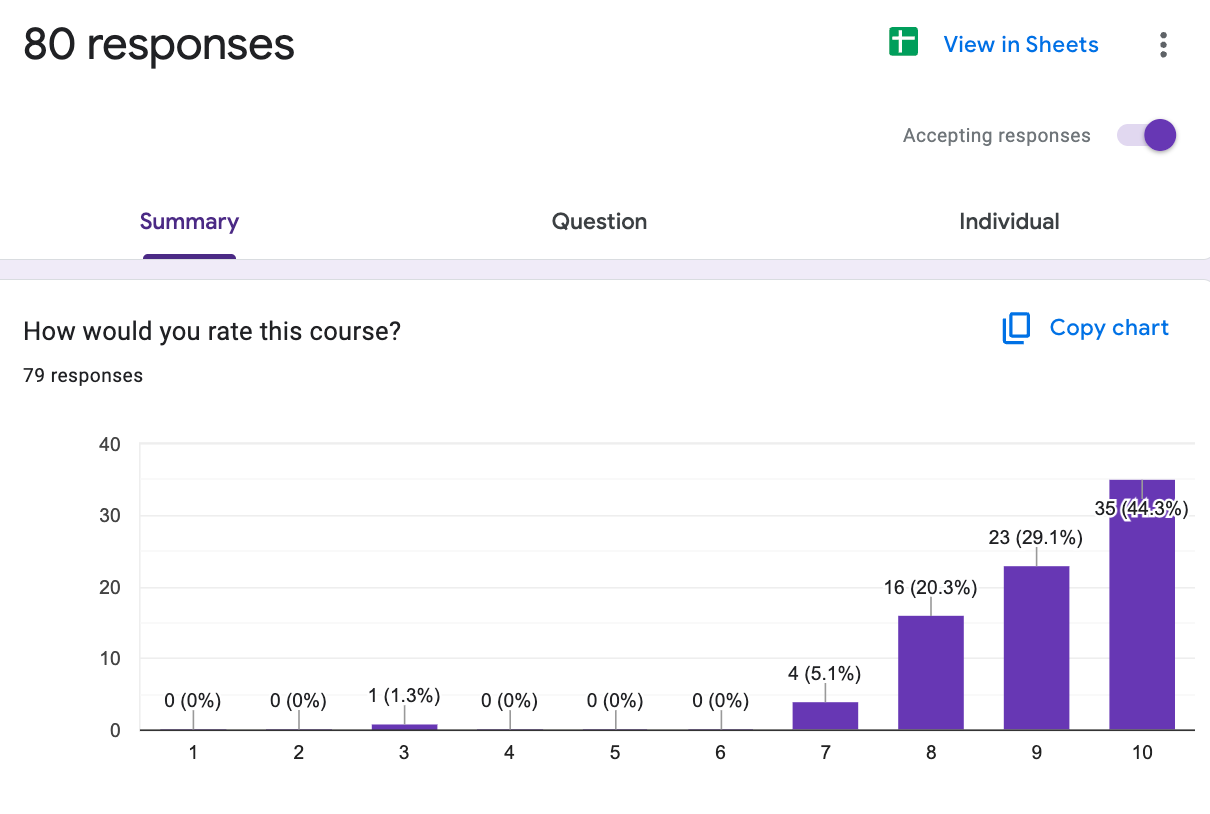

P.S. The Healthcare 101 crash course closes enrollment next week, the Claims Data 101 course is now enrolling

{{sub-form}}

---

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!!

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

Selling to Health Systems (starts 10/6) - Hopefully this post explained the perils of selling point solutions to hospitals. We’ll teach you how to sell to hospitals the right way.

EHR Data 101 (starts 10/14) - Hands on, practical introduction to working with data from electronic health record (EHR) systems, analyzing it, speaking caringly to it, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

Selling to Health Systems (starts 10/6) - Hopefully this post explained the perils of selling point solutions to hospitals. We’ll teach you how to sell to hospitals the right way.

EHR Data 101 (starts 10/14) - Hands on, practical introduction to working with data from electronic health record (EHR) systems, analyzing it, speaking caringly to it, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.