Start your healthcare company outside of the US

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveHealthcare 101 Crash Course

%2520(1).gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

The Healthcare Leapfrogging

I’ve been seeing an interesting trend - lots of digital health companies starting overseas are trying to expand into the US. It’s probably not a new thing, but I’m going to pretend like it is for clicks and clout.

The more common place we’ve seen this is European healthcare companies expanding to the US. For example Tympa Health started in the UK, has been testing in Cambodia, and now is expanding to the US. Current Health started in the UK and was acquired by Best Buy. Sword Health started in Portugal, expanded to the US, and has since raised at a $2B valuation. Many EU companies build out their products in their home country, find the market size is constrained, and then look to the US market which is much bigger. As an Indian man, UK companies looking at markets around the globe is nostalgic.

But I’m starting to see more concepts from non-EU countries that are entering the US as well. I’m building a pet theory that it’s going to be more normalized and logical for companies to get their initial V1 of their product done outside of the US and then come here after.

A few reasons at a very high level:

- It’s incredibly expensive to get started in the US. Basic set up costs, legal, HIPAA compliance, customer acquisition costs, taxes, and every single layer of middleman is taking their cut. Combine that with the fact that a dollar extends much further in other countries + it’s never been easier to plug in remote teams from other countries and it starts looking attractive.

- Non-EU countries have easier access to patient data. We can argue whether that’s positive or negative, but the reality is that looser patient data protections makes it easier to get access to patient data for things like training AI models. Also some countries have centralized repositories of this data like Israel’s four health plans, etc. which makes it possible with fewer contracts to get access to data.

- The business model can be more straightforward outside of the US (even if the total dollars you make are lower).There’s less confusion about getting paid vs. navigating the labyrinth of reimbursement in the US and figuring out what CPT code you need to squeeze into.

- The lack of infrastructure in some countries can be a positive and create opportunities for technological leapfrogging. For one, governments are much more willing to work with companies that can help them lay down net new infrastructure. But also because not having legacy infrastructure can open new opportunities - if no EMRs exist and we were to rebuild that infrastructure today, maybe we might have started with a mobile-first EHR infrastructure. Building that in the US now is untenable. When there’s existing infrastructure, the incumbents will fight tooth and nail to force you to use it.

- This is more of an anecdotal vibe thing but…I think there’s more excitement and interest in “new tech” in other countries vs. a lot more techno-skepticism in the US. Especially amongst doctors, who have been pretty burned by the new tech introduced into their jobs like EMRs.

I think we’ll start seeing more companies get their prototype/V1 done in other countries and work out the kinks + build evidence before coming to the US where the market size is much larger. Below are a few examples of healthcare concepts that have some traction in other countries that I think will be more prevalent in the US down the road.

---

Just FYI, Claims 101 ends enrollment next week. Claims data is some of the most used data for analyses in healthcare. This course goes over how a claim is made, practical issues with using claims data to answer questions, real-world analyses using claims data, and more.

You can sign up and see the curriculum here. Email vishnu@outofpocket.health for group discounts.

---

Low Cost Hospitals and Providers

Thesis: In countries with high out-of-pocket healthcare spend and unsustainable doctor:patient ratios, we’ll see more innovation in delivering care for lower costs.

Hospitals in the US either look like the Four Seasons hotel or Four Seasons landscaping and there’s no in-between. With so much of healthcare spend happening in hospitals, I’ve wondered what lower cost hospital models look like. Most hospitals claim they could never make the economics work on Medicaid reimbursement, but could they if they were reworked from the ground up? Maybe even cash pay is possible.

In India, the hospitals are either self-pay or government run. The self-pay market competes on price and amenities which means trying to find ways to lower cost. For example, there’s a for-profit hospital called Narayana Health that cuts both the patients AND the expenses to the bone (god I hate myself).

“The surgical gowns are procured from a local company for about a third of the cost of international suppliers. The tubes that carry blood to heart-and-lung machines are sterilized and reused after each surgery; in the West, they’re thrown away. The machines themselves, along with devices such as CT and MRI scanners, are used well past their warranties, kept running by a team of in-house mechanics… Even patients’ families are part of the upskilling model. Narayana trains them to bathe patients and change bandages in the hospital, as they’ll do when they get home…Narayana has been able to get the retail cost of a heart bypass, its most common operation, down to $2,000, about 98 percent less than the U.S. average.” - Bloomberg

It’s for-profit and can still make the economics work for complex surgeries. Task shifting is the enabler here, where everyone basically does the maximum they can and the surgeons come in for the highly specialized part that only they can do. Plus thanks to the volumes of people that come through the door, the repetition of doing the same procedures over and over makes things faster and keeps the operating room highly utilized. Prepping a surgery room in the US can take 30+ minutes but for Narayana it’s <15 minutes. For people that want nice rooms, better food, etc. they can pay extra for that.

Could a similarly low cost model be built here from the ground up? You see some inklings of this - Genesis Orthopedics basically saw the Narayana playbook and used many similar aspects of it to bring their costs down and efficiency up. They now take 80% Medicaid patients and seem to make the economics work. The Surgery Center of Oklahoma offers cash pay prices and cuts out a lot of the bloat around facility fees, they’re more price sensitive to supplies, etc.

Maybe we can get even lower cost by stripping away the in-person doctor completely for certain slices of care. Some countries have already been experimenting with this - Ping An in China launched these “AI-powered diagnostic booths” where you fill out a patient intake form and then a telemedicine doctor comes in to finish the appointments. Friends in China tell me these didn’t really take off, but it’s possible that a few tweaks to this model might make it work.

You see some versions of a similar concept popping up in the US. Rezilient has CloudClinics where a doctor telemedicines into a visit and a nurse is the “hands on the body” + uses devices to get vitals. And on the further end of the spectrum, Forward launched the CarePods for $99/month that are largely self-service where you get your own vitals and assessments first with the devices inside and then you speak with your doc/care team after.

I have no idea if these will work, but I do think especially as medical devices and clinical decision support gets boosted by AI you can do more in a smaller space for lower cost. I think other countries with less care accessibility and insurance penetration will actually experiment with these low cost models more since cash pay environments are more competitive and there’s more acceptability to the tradeoff between risk and quality of care. But maybe we can learn a thing or two and eventually try it in the US.

Point-Of-Care and Software-Based Diagnostics

Thesis: In countries with high burden of preventable disease and low accessibility of care in rural areas, there’s more appetite and government buy-in to distribute and reimburse point-of-care testing.

Speaking of smaller devices (😏), other countries might be better places to test diagnostic tools meant to work in the field:

- There’s more government buy-in since the public health burden and economic impact of these diseases are tangible and also fixable. Especially true of farming economies.

- Depending on the tool, you can potentially get a CE mark in Europe that lets you market in other countries. Conversations I’ve had with people suggest the CE mark has traditionally been easier than an FDA approval, but they might be fake friends writing the wrong answer on the mirror for me.

- Bono.

- The volume of testable patients in rural areas is much higher. You’ll get more than 10x the patient volume in most parts of rural India to iterate and improve the product vs. rural parts of the US.

- There’s more available grant and philanthropy money to build and deploy these ex-US.

- Certain diseases are more prevalent outside of the US (e.g. tropical disease, certain infectious diseases, zoonotic diseases, etc.). The pessimist in me also believes these diseases might become more prevalent in the US as a result of climate change and anti-vax sentiment.

So the question becomes can you build high quality screening/diagnostic tools in low-resource settings outside of the US, so that they can then be deployed in low-resource settings in the US like rural areas, a patient’s home, one of the doc-in-a-box things, etc. Some people say constraints breed creativity, others say mosquitoes breed in stagnant water.

AI diagnostic and screening tools are one obvious application of this. For example, Google went out to test its diabetic retinopathy screening tool in Thailand to see how it performed in a real-world setting.

“Google’s first opportunity to test the tool in a real setting came from Thailand. The country’s ministry of health has set an annual goal to screen 60% of people with diabetes for diabetic retinopathy, which can cause blindness if not caught early. But with around 4.5 million patients to only 200 retinal specialists—roughly double the ratio in the US—clinics are struggling to meet the target. Google has CE mark clearance, which covers Thailand, but it is still waiting for FDA approval. So to see if AI could help, Beede and her colleagues outfitted 11 clinics across the country with a deep-learning system trained to spot signs of eye disease in patients with diabetes.” - MIT Technology Review

It did not go so hot lol. But as you can see it was a priority for the government and there’s a huge need because of a specialist shortage. They discovered that things like camera quality and internet connectivity presented a lot of issues in actual deployment, things that will probably be issues in the US too. Lots of companies seem to be doing something similar - VisualDx got funding from the Gates Foundation to help providers in India and Nigeria diagnose tropical diseases like trachoma, hookworm, and echinococcosis (bloods hate that word).

I think an added opportunity here is actually the hardware + AI combination. Ripping and replacing hardware within a hospital in the US is very difficult and there are lots of incentives that push patients to use that hardware in a hospital setting vs. a field setting.

Some companies are testing out their hardware + AI applications outside of the US - Hyperfine has been working with hospitals in Uganda on field use of their portable MRI system and Butterfly’s portable ultrasound seems to be making a huge difference for screening in Uganda as well. Many of the cases they seem to help with are things commonly misdiagnosed but easily treatable (e.g. pneumonia) or require timely intervention (e.g. pediatric hydrocephalus)

Finally, there’s point-of-care assay testing for infectious disease. During COVID, we saw many of these blossom and infrastructure + processes were created across countries to create lower cost point-of-care testing that could be done at-home or in local settings.

Now non-US governments are looking into solutions for dealing with outbreaks of other diseases like RSV, HIV, parasitic infections, tuberculosis, and more. GeneXpert machines have dramatically sped up testing for tuberculosis but the machines are still $10-20K and not financially viable for rural areas. Maybe it could be scaled down and made cheaper? Sherlock uses a CRISPR-based diagnostic that it licenses to help develop tests for things like Lassa fever and tuberculosis + has a foundation called 221b to bring this to the developing world.

There’s a lot of things that make it tough to deploy diagnostics in developing countries - training local staff, poor internet, and everything here about bringing a portable MRI to Malawi like uh….it’s heavy as fuck? But could also present an opportunity for companies trying to build tests designed to be faster, cheaper, and with more diverse datasets.

Delivery Drones

Thesis: In countries with looser transit and airspace regulations, we’ll see more experiments in transporting medical goods. In affluent countries the value proposition starts with convenience. In developing countries it’s around speed and access due to poor road infrastructure.

In 2013 Amazon announced on 60 minutes it was experimenting with drone delivery and people absolutely lost their mind. It took another 8+ years before Amazon started actually delivering via drone because the FAA has a lot of rules around drones flying in the US airspace. But now they’re delivering small, lightweight products including pharmacy meds.

On the other hand, Alphabet’s Wing division (you didn’t know they existed did you?) had been working in Australia and Europe where they had more government buy-in and were testing out their own drone delivery infrastructure. Last year they came back to the US to partner with Walgreens on drone deliveries. The drones still have to ask for assistance to get the deodorant behind the glass though.

I can see the benefits to staying at home when you’re sick and getting your meds without exposing yourself to other people, or mobility impaired people not needing to get into a car to drive to a pharmacy. But honestly the ability to get this stuff within an hour by drone vs. by end-of-day via human delivery doesn’t seem like a huge benefit, which is why I’m guessing uptick hasn’t been booming. As much as people love their KY jelly order being dropped on their front lawn via quadcopter with their neighbors watching, I think it’ll be a while before that becomes mainstream.

However I’m interested to see if this same short distance drone infrastructure will make it easier to deliver higher risk, life saving supplies in shorter periods of time. Think things like defibrillators, epipens, Naloxone, condoms, etc. where the general time window of response needs to be <5 minutes.

The FAA seems to be amenable now to letting companies test delivery drones out in small controlled places in the US, but most of these companies began testing in the EU or Aus and I assume that will also be true for short-distance life saving equipment. The largest deployment of this seems to be in Sweden, where they ran a study of 5 drones sending defibrillators for a year. While the drone dispatch seems to get canceled a lot (1/3rd of the time), when it did deploy it was generally faster than the ambulance by a median 3+ minutes which is considerable in those situations. Eventually the FAA may allow more of these experiments here and we can apply those learnings.

The drones we’ve been talking about so far are much smaller and deliver lightweight payloads over shorter distances. In developing countries we’ve seen the proliferation of large payload drones to deliver in hard to access areas. For example, WeRobotics has several campaigns with the World Health Organization around collecting blood samples from rural villages and delivering vaccines/antivenom to remote areas.

Zipline is a US-based company that started in Rwanda where it used drones to deliver blood, vaccines, and medical supplies to difficult to reach hospitals. This not only worked really well in terms of actually delivering the goods, but also had the effect of hospitals in rural areas not needing to overstock blood units “just in case” since they would end up expiring.

These hospital drone delivery applications potentially have benefits in the US, particularly when it comes to delivering materials to rural hospitals or hospitals-at-home that might not have everything on hand and can be far from a well-resourced hospital. Especially if it saves someone a 30-45 minute drive in each direction.

CAR-T and gene therapy infrastructure

Thesis: Advanced therapies that are primarily created in hospital settings may see faster adoption in countries with more regulatory flexibility, less competitive patient referral issues, and clear reimbursement.

I recently came across this article about a hospital in Spain that brews their own CAR-T therapies called ARI-0001 like a college freshman making dorm mead. The EU has a hospital exemption clause for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMP), which seems to allow hospitals to make CAR-T, gene, and cell therapies themselves without necessarily needing to go through a traditional clinical trial gauntlet like pharma companies usually do. They still need to do things like run preclinical studies, file regulatory applications, get renewals every few years, etc.

Typically these exemptions focus on custom therapies per person for rare diseases. But every country has very different rules around this. For example, limitations on how many patients the hospitals can treat with their bespoke therapies or they can’t do it if there’s a commercial product on the market that went through clinical trials available. But as long as it’s within the rules the government reimburses the hospital.

In the US, these advanced therapies seem to be running into reimbursement issues since they cost millions of dollars. There are also dynamics in place where current fee-for-service reimbursement means that doctors don’t want to lose their patients to academic medical centers that offer the advanced therapies.

“When you talk to these community doctors, they don’t want to give up their patients to the [academic medical centers] too soon,” Graybosch said. “They have something for them, they can give them another standard-of-care treatment.”

Kite’s Yescarta has enjoyed better uptake in Europe because the government is the only payer in many countries, Biddle explained. These unified healthcare systems “don’t have the same incentives or disincentives” that the U.S. has to keep patients within their own network.” - Fierce Pharma

More like Nocarta. Maybe hospitals in the EU develop expertise faster in delivering CAR-T and gene therapy treatments? Over there hospitals can basically bring a drug to market for much lower cost - the drug from that Spanish hospital was $97K or 1/3rd the cost of the existing commercial CAR-T drugs.

Single payer countries don’t face the hospital competition issues like you see above. This is also important because so few patients currently need these advanced therapies and they’re so complicated to actually administer. So it might make sense to have patients funneled to one place that specializes in delivering these advanced therapies to get more practice with more patients vs. having several hospitals build the capabilities and compete for a small pool.

There’s something interesting here. For a curative therapy, it’s also definitely possible that people will travel from around the world including the US. CAR-T makers in these exemption countries could figure out things we’ve struggled with in the US for these drugs. Things like outcomes-based payments, monitoring of patients before and after, supply chain logistics of moving the therapies around, etc.

In the Barcelona example they talk about how the hospital had to build a whole layer of expertise around the basics of drug development. Maybe a new contract research organization (CRO) can specialize in hospitals doing this in the US with lessons from the EU:

“In both Europe and the U.S., there’s no rule preventing an academic group from trying to run the full gauntlet of drug development. It’s just not something they typically do.

Steering the pivotal trials and filing regulatory applications — let alone marketing a product — requires money and specific expertise that drug companies may have but that doctors more focused on treating patients and publishing papers do not. Academic medical centers might also be nervous about unknowingly stepping into a fight over intellectual property rights, or opening themselves up to lawsuits if something goes wrong with the treatment…

But the researchers said they wanted to push forward with the ARI-0001 work on their own both to show it was possible for an academic group to design, make, and test such a therapy, and to expand access to patients who might not be helped by a pricier commercial product. -Stat News

If there’s success abroad, we might take the lessons from hospitals in those other countries and apply it to advanced therapies here. Or maybe we’ll see global competition where patients fly to specific hospitals specializing in creating curative therapies for certain disease areas.

But it’s still early - this exemption came out in 2007 and was before the boom in curative therapies. All of it is still a pretty gray area and there’s very little standardization around what each hospital needs to demonstrate they can deliver these therapies, which critics say yields less quality oversight.

Who knows if this exemption ends up tightening + the US is usually not one to fall behind on the pharma side of things. So let’s not put the CAR-T before the horse. 😩😩😩

Non-Healthcare Data for Risk Stratification and Interventions

Thesis: Countries that have applications that have easier access to data and more involvement of life insurance in healthcare will find ways to use novel datasets in patient risk stratification.

I know my ideas are pretty half-baked but this one is like salmonella levels. This newsletter is a chance to refine it and get your thoughts.

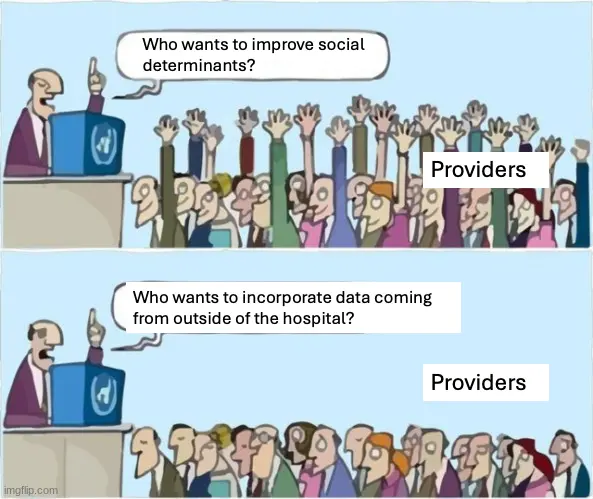

A common idea we’ve heard in the US is that non-healthcare things can impact health outcomes aka social determinants. But right now it’s very difficult to get providers to actually help with social determinant issues, or even use data related to those social issues in your care plan. What if I could just give my physician (or the care team around them) access to my grocery shopping app, or my geolocation data, or my credit card data and ask them to find anything there that might be causing health issues for me? Other than the unfathomable amounts of whippits it takes to write one of these newsletters.

I think the gut reaction is that it’s too much messy data that docs don’t want. No one will be able to interpret anything out of it, draw clinical conclusions from it, or even have the time to provide that level of handholding like grocery shopping to patients. But I think the advent of AI agents that can do things like make appointments, shopping lists, call places, interpret data, etc. make this data potentially actionable.

Despite it potentially being usable, I don’t think giving that level of personal data will happen in the US for a while because of attitudes around data privacy and the fact that this puts a lot more work on the existing healthcare system for no additional payment or benefit. Maybe value-based care teams could benefit from something like this, but the effort is usually so monumental vs. lower lift things they could do to reduce spend.

But I think there’s potentially something interesting here in other countries for a few reasons.

For one, other countries have Super Apps where you do everything from healthcare to shopping in one app. Line in Korea/Japan, WeChat in China, Grab in Southeast Asia are all examples. Being able to co-mingle data from things like grocery/eating out, location, or other behavior related stuff with your telemedicine appointment would be much easier if you stayed within the app.

The other reason is because life insurance and health insurance are frequently sold under the same umbrella, and these companies already use a lot of this data. In the US there are pretty strict laws that separate life insurance, health insurance, and care delivery. In other countries these can be bundled - Discovery from South Africa has medical, life, auto, financial products, and travel related stuff like lounges. It combines all of these things to reward you for doing healthy stuff like lowering premiums or giving discounts on healthy activities in exchange for users opting in to giving them data. You can see a lot of how it works in this deck.

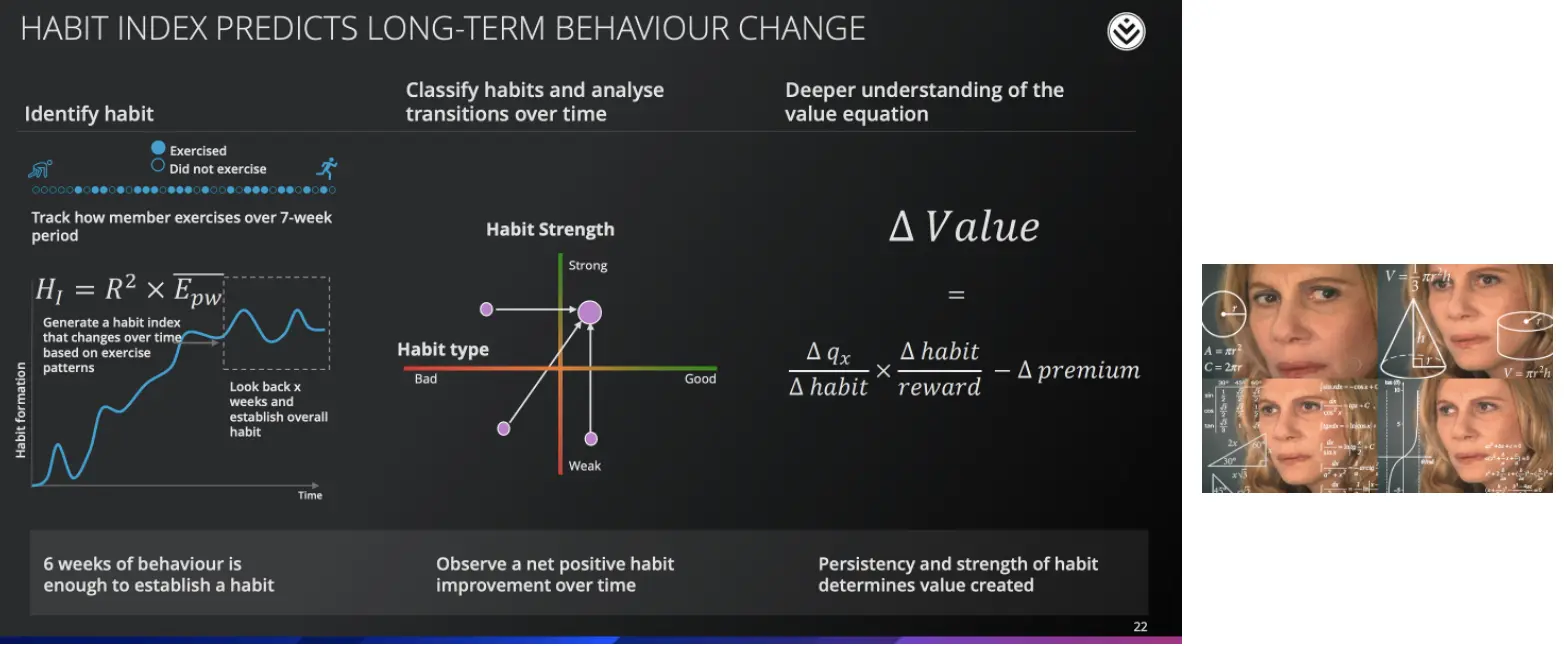

In their earnings presentations, Discovery talks about using all these different business lines to underwrite the risk of their populations. This presentation goes through some very…creatively designed charts on how they analyze this stuff. They also talk about how they personalize rewards to help people develop habits and then have some “Good Will Hunting”-ass equation to figure out how they change the premiums.

This stuff lays the groundwork for new ways of risk stratifying patients using alternative data that might be useful in the US. John Hancock is a life insurer that licenses the Vitality algorithms from Discovery for its underwriting, maybe other insurers or value-based care providers might do it too. You might also see companies like Discover use all the data that their members give to find unique ways of intervening in people’s daily lives to take more healthy behaviors.

In fact, in 2018 Clover Health did this with Cathay, a conglomerate in Asia Pacific that has many subsidiaries including life insurance and hospitals. According to this report, the Cathay At Your Side program was meant to identify high-risk life insurance policyholders and work with their hospital division to actually get those policyholders to adopt healthy behaviors (diet/exercise) while the user uploaded health data to an app. In other decks, Cathay talks about how they segment their clients into risk categories using personal behavior data, social data, etc. When you start piecing these together you see a company already using non-healthcare data to risk stratify and help patients, it just happens to be in life insurance.

We can take some of the learnings from how other countries use non-healthcare data so that care teams can better identify high-risk populations and intervene at the right times. But a whole lot is going to have to change around data privacy before people here will be okay with their dietitian calling them and telling them to lay off the chocolate after seeing it show up in their grocery data.

Conclusion and parting thoughts

Thesis: I need this section because I'm still unlearning college writing habits.

The idea of testing ex-US is not really that novel. Pharma has been doing it for a long time with clinical trials because it’s sometimes cheaper to recruit/run the trials, there can be less oversight, and they need representative populations for global approvals.

But other types of healthcare companies might now find it’s better to test in other countries for the reasons we’ve laid out. But it’s worth noting that there’s lots of reasons that translating a product from another country into the US won’t work:

- Your care model does not translate because of differences in what clinicians can do in each country, the patient population, etc.

- The economics no longer work because there are lots more middlemen + compliance related costs you need to pay

- There’s no nice reimbursement option for you to fit into once you get here

- You have no choice but to use the legacy infrastructure in the US like EMRs, etc.

- Regulatory bodies or payers want more data on a representative US population

But some really disruptive ideas will emerge in other countries and become adopted in the US, especially the ones that can appeal to consumers directly. If you have any other examples of healthcare ideas that are working in other countries and could make their way over to the US, let me know.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “You’re in foreign whips, I’m in foreign care delivery models, we’re not the same

Twitter: @nikillinit

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

Thanks to Gaurav Singal and Morgan Cheatham who read drafts of this

--

{{sub-form}}

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.