Weird health insurance concepts

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveNetwork Effects: Interoperability 101

.gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Hi, here’s my attempt for the Guinness Book of World Records for lowest open rate by sending this out today.

I was thinking about what self-destructive behavior I could turn to to take my mind off things, so I decided to write about some niche health insurance concepts that you all might find interesting. Turns out, this is actually worse than just heavily drinking.

Maybe we’ll learn a thing or two about intercompany eliminations, co-pay accumulators/maximizers, and reference-based pricing.

Intercompany eliminations

The Number 1 rule of health insurance carriers is they hate paying for stuff. The Number 2 rule is to consider merging with Humana every 5 years.

Insurers hate paying for stuff so much, we introduced a rule called medical loss ratios. This essentially says that for every $1 in premiums they collect, they HAVE to pay out $.85 of that in medical claims (or $.80 depending on the type of insurance). A well-intentioned rule meant to prevent health insurance companies from hoarding cash on that Smaug life.

However, what happens when you effectively cap the profits a health insurer can make? Well…they start moving into non-health insurance segments. That's one major reason you see so much vertical integration where payers, pharmacies, pharmaceutical benefits managers, and providers are all coming under the same roof.

But what makes this dynamic particularly interesting is not just that they can make money in other business lines. It’s that the insurance company can pay its own subsidiaries for care, which allows them to count it towards the medical loss ratio.

This is called an intercompany elimination. Despite sounding like Squid Games to reduce headcount, it’s an accounting thing not specific to healthcare. It prevents companies from double counting revenue if they pay their own subsidiary. If a company makes $100 and pays $50 to a subsidiary it owns for services, you can’t count it as $100 + $50 in revenue for the company.

This intercompany elimination becomes more important in health insurance because of the medical loss ratio and because I need to say that to stay relevant.

Regular scenario: UnitedHealth collects $1,000 dollars in premiums (lmao I wish). You go see a regular doctor that charges $850 dollars for the visit. UnitedHealth pays it, and UnitedHealth maintains its medical loss ratio of 85%. They keep $150.

Intercompany elimination: UnitedHealth collects $1,000 dollars in premiums. You go see an Optum-owned physician. Optum charges $850 for the visit. UnitedHealth pays it, and maintains the medical loss ratio because it paid out 85% of premiums it collected in claims. But now they keep $150 + the $850 they paid out since Optum is under the same umbrella.

But it’s not cheap to run the Optum clinics since they employ physicians, staff, etc. If that visit costs $600 in expenses to UnitedHealth, they still make money. However, if that visit is $900 in expenses, then UnitedHealth loses money.

A payer could also theoretically deliver care at cost or even lose money when they own the clinic, and their argument is that it helps curb costs and introduce competition into the provider ecosystem. Or they might purposefully steer a patient away from a really expensive hospital visit and push them towards a cheaper care setting, that’s potentially more cost-effective.

It’s not just providers either, but also drug spend. As drugs become more expensive, owning the pharmaceutical benefits managers and specialty pharmacies that dispense the drug also starts feeding into intercompany eliminations.

Intercompany eliminations are no longer a fringe part of health insurance carrier strategies. In fact for many of them it’s where they see the most margin growth in their business. An anonymous health insurance exec once told me “fuck it we ball” when I asked them about this.

Insurers will make the case that your benefits are more coordinated when they’re under one roof and they’re more financially incentivized to keep prices lower for patients. Opponents will make the case that health insurance carriers now bully out small clinics and pharmacies in favor of their subsidiaries + have incentives to use cost-saving tactics that might not be in the best interests of patients.

Up to you on who you want to believe, I’m just here to explain a little accounting magic that makes it work.

Last call for courses

Did all this talk about health insurance make you intellectually aroused in ways that are hard to explain to colleagues? We have the solution for you!

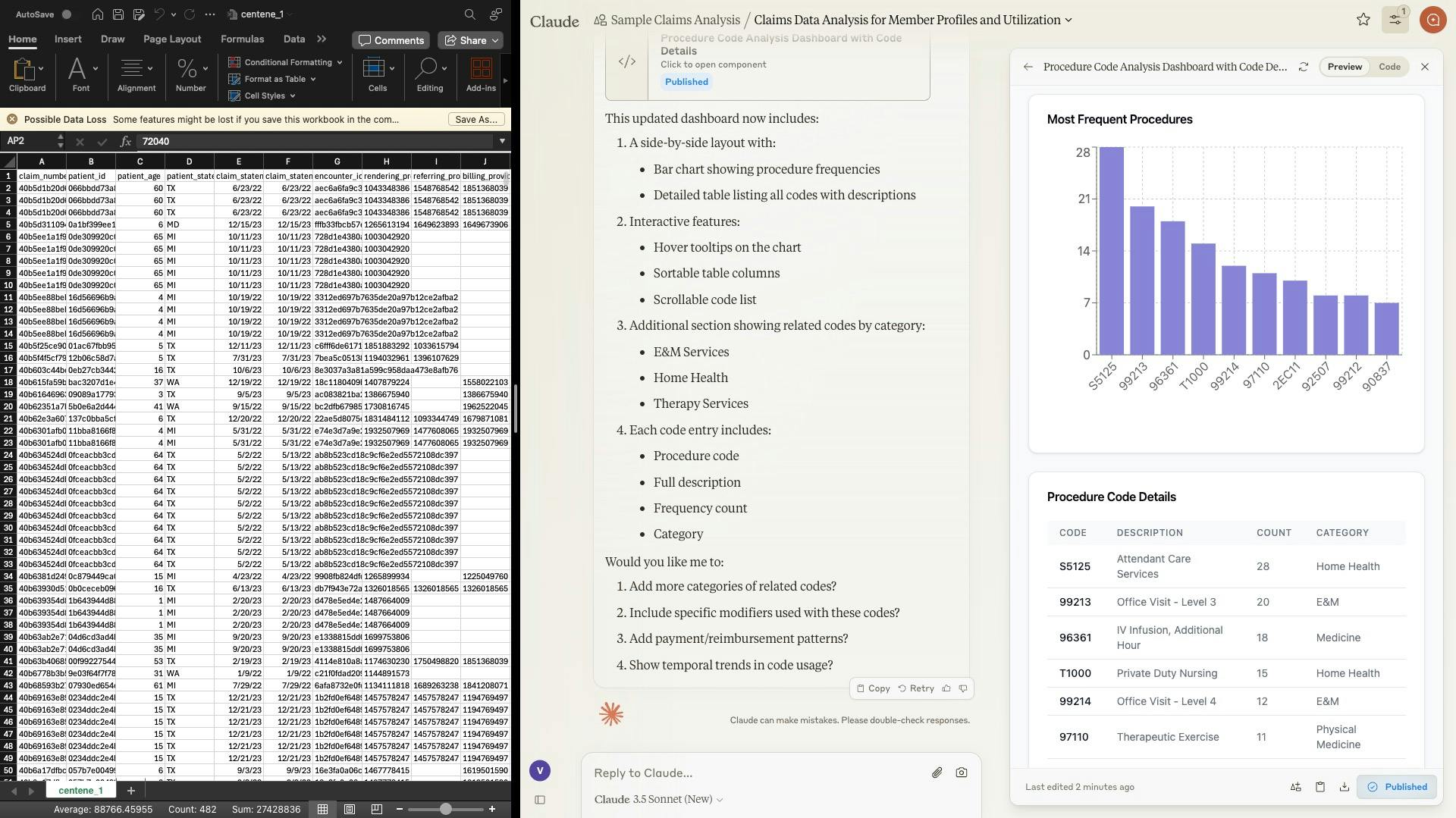

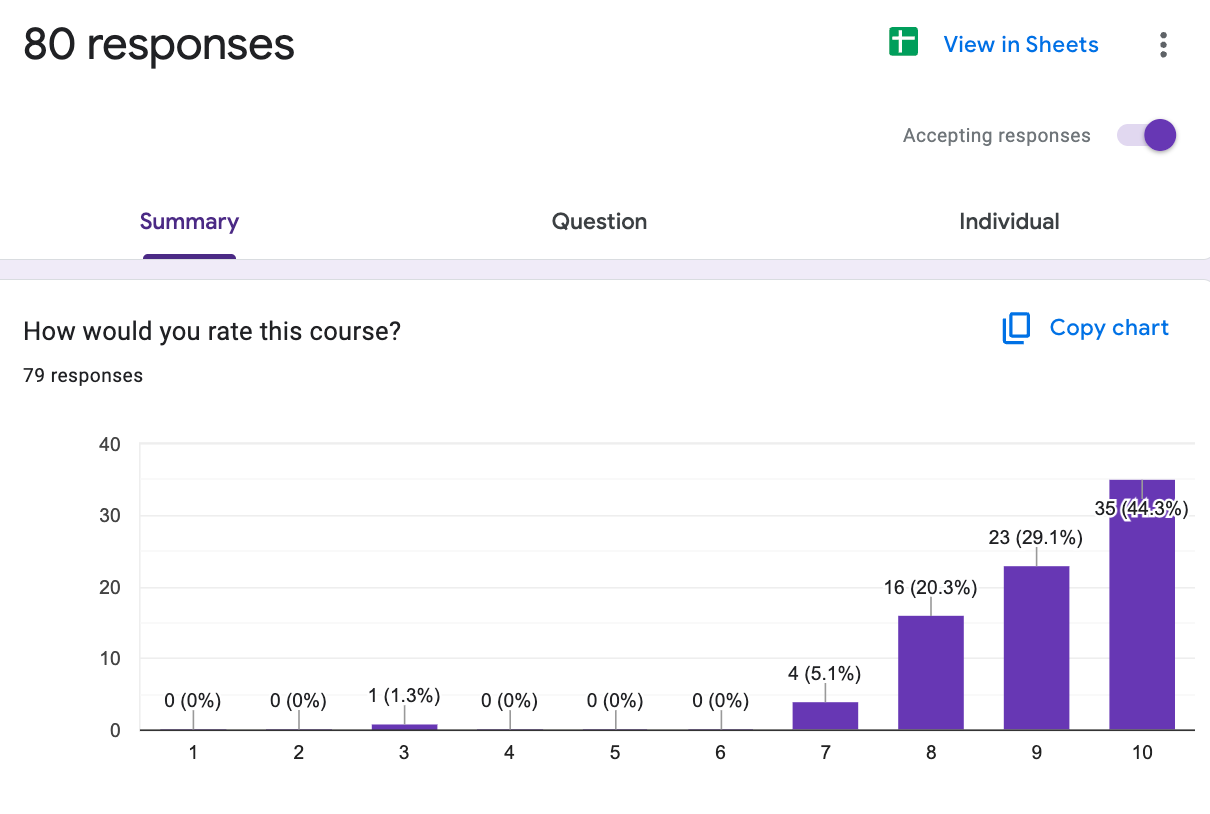

Our claims data 101 course ends enrollment this week! You’ll learn everything about what’s in and not in claims data, how to acquire claims data and use them for real-world analyses, and go through case studies that’ll teach you. Were testing some GenAI stuff too, like a walkthrough how you can use Claude to write code to visualize and understand the codes without needing to google or use CPT codes to reference.

If you want to get a little closer to the payer “action” (relax there bud), we have a course that will teach you how to get in-network with payers, negotiate contracts, and pitch them. How to contract with payers starts 12/2.

By popular demand we’re formally launching our LLMs in Healthcare course. This sold out in 5 days for the beta, and goes through how large language models work, some real-life deployments, how to evaluate them, and more.

If you want to sign up groups or your company for any of these, we offer some discounts. Reach out to us here.

Co-pay accumulators and maximizers

Here’s a sort of fun one between pharma and insurance. There are a lot of details I’m leaving out to just get the point across.* I already know I’m going to get a lot of “BUT ACKSHUALLY” emails on this.

Let’s say you need to take a drug that costs $1000 a month, and you need to pay $100 copay to get the drug. That high copay might end up preventing people from taking the drug. It is in the pharma companies best interest for people to pay the $100, because it means they’d get $1000. So a pharma company might go to the patient and say “hey, why don’t we just cover that $100 you have to pay?”.

This is the concept behind manufacturer copay cards. It allows pharma companies to access the much higher insurance reimbursement by paying the patient’s copay for them. It also let’s them flex their strength in squeezing as many disclaimers as possible into small spaces.

This is great for the patients that don’t have to pay anything out-of-pocket, and great for the pharma company that now gets the much higher insurance reimbursement by essentially gaming the copay system. But the insurance company doesn’t love that obviously because it’s against the intent of the copay and prescription drug coverage design.

So the insurance company has created two mechanisms now to handle this.

- Co-pay accumulators - A co-pay accumulator essentially prevents that manufacturer coupon card from applying to your deductible. For a patient probably has lots of other spend, this can make the card seem less attractive since they’re trying to hit their deductible. This also means that effectively the plan gets paid two deductibles, the amount of the copay assistance AND the amount of the patient’s deductible.

- Co-pay maximizers - If the insurer knows that the manufacturer is going to cover the cost of the copay…well what if you made the copay extremely expensive for just that patient. Co-pay maximizers essentially create artificially high copays for a specific patient that try to maximize the amount the pharma company will pay in assistance. If an assistance program offers $12000 per year, then a maximizer will “adjust” that specific patient’s copay to $1000 per month. So the patient is shielded from the costs, but the pharma company pays MUCH more.

Below I tried to illustrate how the money comes out of each pocket for a drug that costs $20,000 a year where the patient has a $5,000 copay, a $5,000 deductible, and a co-pay assistance program that maxes out at $15,000.

- For the regular scenario, the patient pays $5K themselves

- With co-pay assistance, the pharma company pays the $5K copay

- If an accumulator is applied, the pharma company pays the $5K for the copays but it doesn’t count to the deductible. So the patient still has to pay $5K if they get any other healthcare stuff.

- If a maximizer is applied, the pharma company pays the co-pay but the co-pay is now $15K. The patient doesn’t pay anything, and the amount out of the insurance company is way lower.

And so…pharma companies aren’t happy about these new tools. So now you see them fighting back by sending debit cards to patients or trying to mail the patient “rebates” that the insurance company can’t track in the claims data to apply the accumulators and maximizers.

This sounds very normal! A program that isn’t marketed, and uses “receipt” in quotes! This industry works well!

Just think of all the administrative spend just tracking all of this, like 5000 jobs are probably created from this. Pharma and payers are both at fault here. Patients are caught in the middle without understanding what’s going on with their co-pays and need to navigate an unnecessarily complex maze of financial incentives to figure out how to pay for them.

In my opinion, copays for drugs are dumb anyway. If the argument is about whether a patient should be able to get a drug, it should happen at the prior authorization level. Not whether or not a patient can afford to pay their copay, which ends up hurting poorer people way more. And it leads to these silly games where both sides are activating trap cards to outsmart the other.

*There’s a lot I’m omitting from this explanation. Like this whole thing is only for commercial patients and branded drugs. These programs are usually a combination of payers, PBMs, and third-party vendors that help with these programs and charge fees. Drug Channels has some very good walkthroughs of this + this article is quite good if you want to go deeper.

More course stuff

We have a few courses that kick off right at the beginning of next year too. If you want to sign up groups or your company for any of these, we offer some discounts. Reach out to us here.

- Healthcare Product 201 - For people that want to be excellent at product in healthcare. Everything from how to bring a product to market, thinking through building a business case, case studies from products that came to market. And more. Starts 1/6 (yikes).

- US Healthcare Crash Course - Taught by yours truly and goes through all the main players in US healthcare, how money flows, major laws, and more. Starts 1/28 (this time from 5-630 PM ET each day)

- EHR Data 101 - Hands on, practical introduction to working with data from electronic health record (EHR) systems. Learn practical strategies to extract useful insights and knowledge from messy and fragmented EHR data. Starts 1/28.

- Selling to Health Systems - If you need to sell to hospitals, you’re gonna need the map to figure out how to get to the person you need and explain your value proposition. This course will actually help you work on your pitch. Starts 2/3.

Reference-based pricing

How do hospitals and payers figure out how much the hospital is going to get paid for a service? Both parties go into a room, make a blood sacrifice, and Cthulhu utters a number.

Typically this is a long and complex negotiation across every single service the hospital offers that’s based on market concentration, leverage, etc. It usually starts from some arbitrary price a provider says a procedure costs, and then negotiates down from there. At the end of it, you have a contract that explains the prices the insurance will pay and rules for payment.

Effectively every price is negotiated in a bespoke way, which is why you end up with a million different prices within each hospital. One thing we talk about in the healthcare 101 course (starting 1/28!) is that commercial health insurance payers basically always pay more than government plans do. And it can be substantially more - like 6x for the same exact service in the same hospital in some cases!

But another way to approach a negotiation is say…no contracts needed. When a patient goes to the hospital, we’ll give the hospital __% (e.g. 120%) of whatever Medicare pays them for that service. Medicare is the reference price, and the reimbursement is based on that.

So effectively every single doctor and hospital is out-of-network and is then offered this relatively standard pricing methodology as reimbursement when the bill comes.

This is almost exclusively offered by self-insured employers that need to use a third-party claims administrator that is unaffiliated with the health insurance plans. However many states will also use this methodology for the health plans that cover people that work for the state or public functions like teachers.

Proponents of reference-based pricing will talk about the benefits like:

- The methodology for getting the price is easy to understand for both parties instead of a complex negotiation. The prices are much more transparent as a result.

- There are no “networks”, so patients can more freely see who they want. And because you can tell employees “we’ll only cover X% of Medicare, so shop around”, they are much more exposed to the cost and shop themselves. Providers theoretically have to compete for them.

- Employers are better able to contain costs because of the above but also because the % of Medicare is usually lower than what they can negotiate themselves.

However, the main argument against reference-based pricing is that you’re putting a patient in the middle of a bill negotiation between the employer and provider. That can get really awkward if the provider says they don’t accept reference-based contracts and to reference deez nutz. Or if the negotiated rate isn’t enough for them and then they bill the patient directly for the rest of the amount. As you can imagine, hospitals do not like reference-based pricing and fight back against it.

Reference-based pricing is basically an out-of-network bill that you sort of know your employer will cover but it COULD go sideways. This creates a lot of uncertainty, and in-general this shopping aspect with no networks is very new to most people. So implementing a reference-based program requires a lot of hand-holding and education of employees and an excellent system to help them search where to get care and negotiate bills.

In general it’s an interesting concept though. Many companies have tried going down some version of this route like Castlight, Sana Benefits, Medxoom, Daffodil Health and more. The success here seems pretty mixed and dependent entirely on how willing employees seem to be to try to learn this and how willing providers in a given geography are in accepting this arrangement.

Final thing - a health data happy hour!

We’re co-hosting a healthcare data happy hour with Hex in New York on 12/11. There’ll be 5 ten minute “flash talks” on things related to healthcare data and then drinks/food.

If you’re a healthcare data person and want to come, fill out this form. We have some space constraints so we’ll be limiting it to the people that fill this out.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “Probably should have taken a look at the calendar for posts”

Twitter: @nikillinit

IG: @outofpockethealth

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

--

{{sub-form}}

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!!

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

Selling to Health Systems (starts 10/6) - Hopefully this post explained the perils of selling point solutions to hospitals. We’ll teach you how to sell to hospitals the right way.

EHR Data 101 (starts 10/14) - Hands on, practical introduction to working with data from electronic health record (EHR) systems, analyzing it, speaking caringly to it, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →Our Healthcare 101 Learning Summit is in NY 1/29 - 1/30. If you or your team needs to get up to speed on healthcare quickly, you should come to this. We'll teach you everything you need to know about the different players in healthcare, how they make money, rules they need to abide by, etc.

Sign up closes on 1/21!!!

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.