More weird issues in value-based care

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveIntro to Revenue Cycle Management: Fundamentals for Digital Health

Network Effects: Interoperability 101

.gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Wait…you all don’t like value-based care?

Last time I posted some thoughts on value-based care through an optimistic, neutral, and cynical lens. I asked for your thoughts on value-based care. You basically all sent me cynical ones lol.

There’s definitely a lot of selection bias based on who’s on and who responded to the newsletter, but I was surprised at how much frustration people vented to me about value-based care. Some really interesting stories in how value-based care manifests in product, operations, and clinical work.

Below are some of the more interesting answers I got.

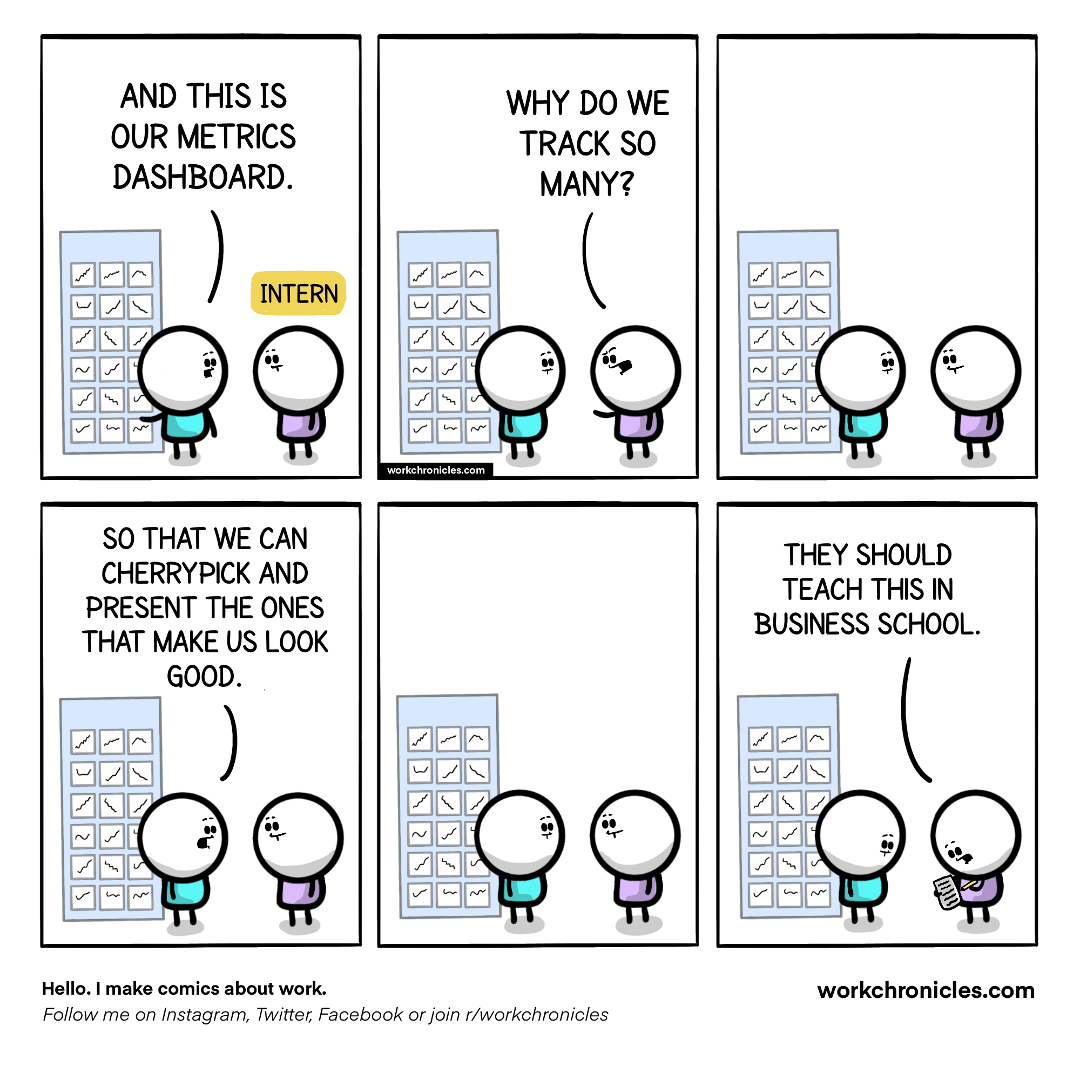

Cherry picking can be productized

“As a product manager who has been working in healthcare tech/VBC for a decade, this post piqued my interest. You indirectly alluded to this in the "cynical take" section, but I wanted to comment on it further. Cherry-picking is an unfortunate yet prevalent side effect of certain value-based care models. While VBC seeks to incentivize providers to improve quality while controlling costs, it can inadvertently encourage some organizations to prioritize low-risk patients to maximize performance metrics and reduce financial penalties. This undermines the equity goals of VBC, as the most vulnerable populations—often those with the greatest healthcare needs—are left behind.

I've seen how the drive to meet certain performance metrics can distort care delivery. In my experience, I've designed tools that aimed to improve patient outcomes across the board, but it became clear that systems with value-based incentives actually wanted tools that identified the "easier" patients. For example—a high BMI, which fails to account for muscle mass, body composition, and other individual health factors, always led to patients being labeled as "high-risk." This can lead to healthcare providers deprioritizing or avoiding these patients. I'm not saying VBC isn't the answer, but if it's going to succeed, we need better metrics that capture a patient's true health profile rather than using outdated standards like BMI, which can result in cherry-picking patients for better outcomes.”

[NK note: It’s such a delicate dance - if you set measures to get the riskier patients, you end up with people gaming risk adjustment and making patients seem sicker than they are. But if you don’t give good bonuses, you end up with this kind of cherry picking.

It’s also interesting how now the conversation about outdated metrics stacks issues on TOP of value-based care programs that rely on those metrics.]

—

The admin overhead is the same

“I’ve been with Landmark Health for a few years now and my biggest beef with the home-based value-based primary and wrap around care model that we run is that we don’t have any less administrative overhead than a fee-for-service clinic.

We still have to submit claims to our payers ($0) to appropriately log disease states and close quality gaps so our payers can get that sweet sweet RAF/Stars cash, so we have to have coders/coding/claims infrastructure. We have a mix of PMPM and over/under risk-based contracts so we still have a full billing and revenue cycle management department, with additional analytics FTEs layered on top to ingest the tons and tons of claims data to see where we could be doing a better job (population health is so data-heavy and data infrastructure isn’t cheap!).

We’re “at risk” for costs for a large chunk of our patient cohort but our staff still has to submit prior auths and letters of medical necessity and appeal denials for rxs, outside services and DME that we order. And at the end of Q4, we’re doing a lot of unnecessary visits just to close as many HEDIS gaps as we can before the deadline. As far as cost savings, I can’t really see how VBC makes providing care any more affordable from a provider perspective; the only advantage is that with nearly the same amount of money coming in, VBC arrangements do make it possible to be more creative with what we offer to our patients because we’re not beholden to a fee schedule and rigid visit types for the sake of cleanish reimbursement.

I like where you’re going on patient-driven outcomes being part of value-based care. I’d be curious whether folks in value-based care arrangements will start to take those arrangements for granted, as all baby boomers seem to do with the good things that society has developed for their benefit (SOCIAL SECURITY. MEDICARE. SENIOR DISCOUNTS.). Our practice gets decently high NPS scores but there are always comments like “They call me to check in too much” or “They were 20 minutes late to my home to see me for an urgent visit appointment that I scheduled at the last minute in a snow storm” that make me think that consumers will never be happy with any kind of care, even the kind that comes to them without any out of pocket costs.

Like, if you have that much to say about a company that sends a provider to your home for free, can you ever truly be happy about anything?

VBC has the same challenges as FFS in the sense that consumers want to believe they have a choice in both their insurance coverage and their care providers/services, but both systems remain too convoluted for a typical patient to be able to compare and determine whether they did in fact have a better experience or outcome in one arrangement over another.”

[NK note: So much of this seems to be about retrofitting old infrastructure like claims processing and trying to make value-based care work so that we can escape a different old infrastructure (payment rails). What if…we just created more flexible payment rails and see what happens instead?

I think we need to make the payer landscape more competitive so they’d actually try to build payment rails from scratch.]

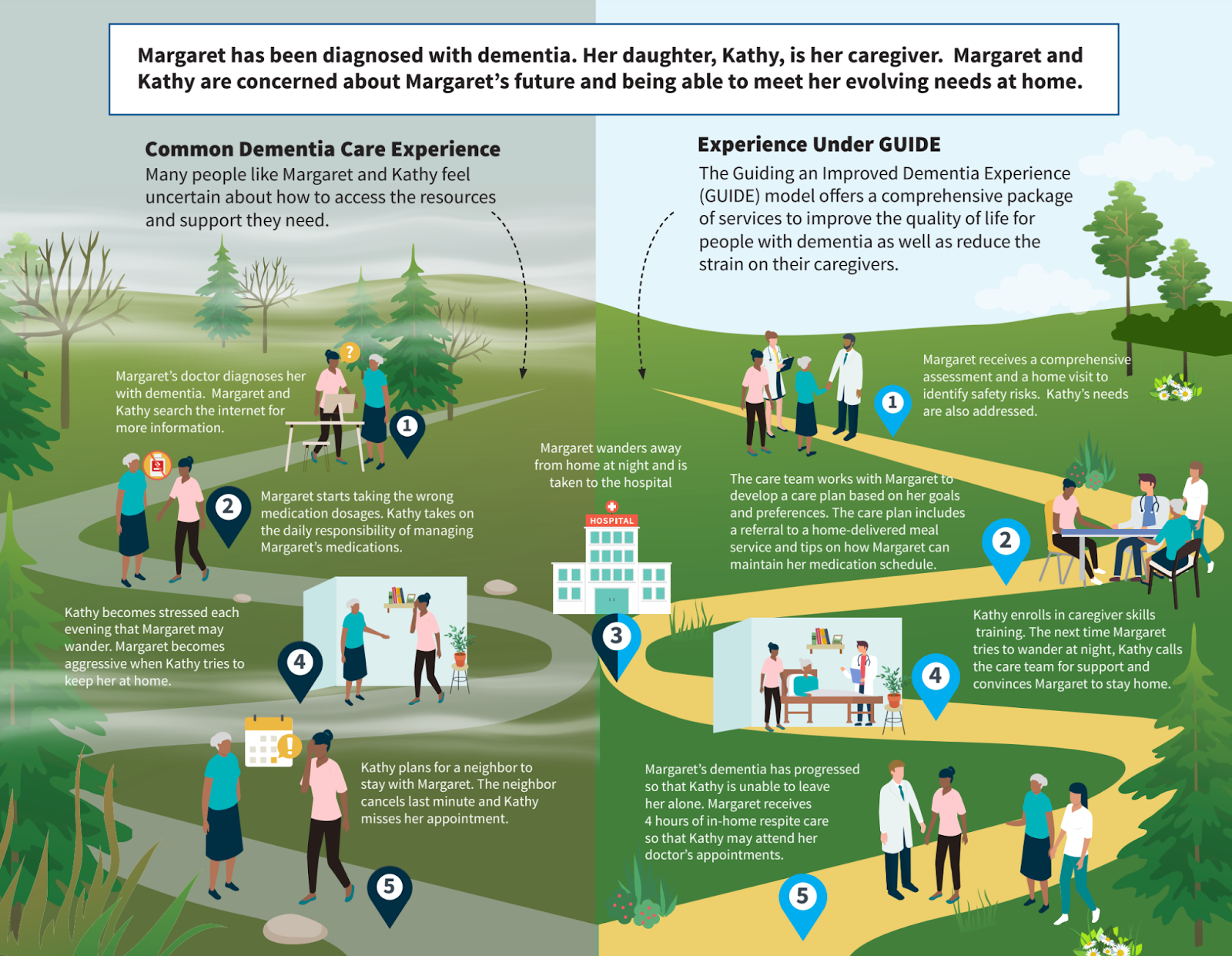

Fee-for-service actually incentivizes better care in dementia?

“Another interesting thing is that everything becomes a fixed cost…let me explain

In fee for service, clinicians work in RVU model which with all its downsides does mean that complex patient encounters can bring more revenue—I’m seeing a Dementia patient for Medicare, let me do x x x things and bill and bring them back every three months. Patients feel extremely cared for and dementia is a great example as education and supportive care are the main interventions

In value based care, there’s risk adjustment for the Dementia patient so I get a lump payment to “take care of them”. But there’s no metrics specifically for dementia care and clinically, there’s no “medical interventions” (meds exists but they’re not that great.) So after I see them once, why should I see them again if no clinical care is needed?

VBC: dementia diagnosis, supportive care, 20 min visit. (No incentive to do more). Less follow ups=more access for other patients as doctors are fixed cost-both salary and time.

FFS: dementia diagnosis, 40 min visit, more follow-ups. More follow ups=more money

[NK Note: CMS has a new model called GUIDE that focuses on dementia - the focus is more focused on using non-clinical members of the team as support that can still get paid]

Almost seems obvious of the whole “doing less” and harming patients critique of value based care…but how it actually goes down is this:

- I pay doctor a salary (maybe some value based incentive but not RVU based)

- I’m not getting paid by encounters no matter how complex

- If each visit brings in the same value (not RVU adjusted for complexity), we need to have as many visits as possible to maximize our resources. Decreasing costs increases profits in value based care! People think value based will mean longer visits since it’s not RVU based incentivizing volume but it’s funny how it all works out.

- The most efficient use of doctors time is to do 20 minutes for the patient and free up time to see others to increase access for the population we have to take care

Medical outcomes could be the same (research shows that probably is true) but patients feel so much better and “cared for” in the FFS situation. You want to see me that much and tinker with meds that may or may not help, thank you!!

But this is true for hospitalization follow ups and a whole number of situations…”

[NK note: This makes sense in areas where it’s not super clear which cost levers you can pull or what you can do to really move the needle on outcomes. This seems to be the case in dementia, which means your goal instead is to reduce utilization/amount of care they receive since you don’t have any other tools to change cost-effectiveness.

The argument at a societal level then becomes whether you do actually want doctors to spend more time with patients when there’s not a whole lot they can do but it’ll make the patient feel more heard and comfortable. If the answer is yes, fee-for-service actually might make more sense. If the answer is that the doc should spend more time with different patients who could get better, then maybe VBC makes more sense.]

Interlude - Knowledgefest

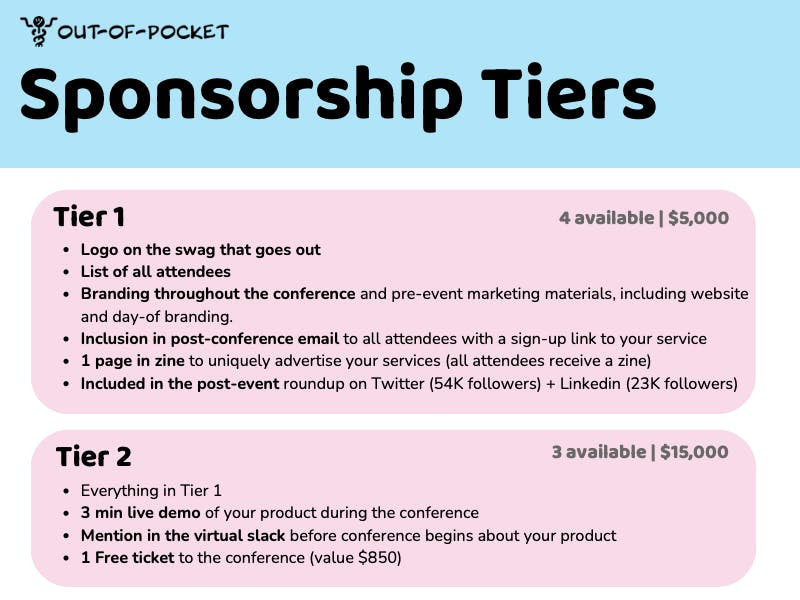

This is the final week we're taking sponsors for the Knowledgefest conference happening in SF on 11/16. This is an invite-only conference for people in the healthcare operations role.

We have a single Tier 1 and Tier 2 sponsorship left. If you get either before the end of the week, we'll throw in a free banner ad credit to use in the newsletter.

Email knowledgefest@outofpocket.health if you're interested. If you're trying to get in front of healthcare ops people, this is for you.

From the front lines of bundled payments and BPCI

“I'm excited to give my thoughts, though, as someone who worked very closely on BPCI at one of the best ortho hospitals in the nation and the cool things we were able to do when you have the opportunity to innovate. Also, as someone who went into the startup world and has been "trying" to re-create my success in BPCI in conservative specialty care management.

I was extremely optimistic 3 years ago about value-based care. Seeing groups like Oak Street and Cityblock first pop onto the scene, I really thought, hmmm, maybe we can actually make this work. Fast forward three years, and the 100s (maybe 1000s) conversations with commercial payers and large medical groups have changed my tune from highly optimistic to borderline pessimistic.

First, For-Profit Commercial Payers....For-profit commercial payers have no great incentive to participate in complex custom attribution models of costs and outcomes. 1. Their systems are antiquated FFS machines, so why invest in proprietary software or spend a bunch of money on Change Healthcare episodes to deviate from what has made you a lot of money in the past? You know the saying, if it's not broken, why fix it? 2. They figured out that vertically integrating care delivery services with payer operations is much better for shareholders when you can skirt around your M/L ratio. 3. It's SO much easier to say you are a value-based care insurance company because NOBODY knows what value-based care is anymore. The term has been overused to the point that if I go onto any startup, hospital, or insurance website, I can guarantee that I will find a "Value-Based Care" section and how they are the best at implementing it.

[NK note: Putting “value-based care” in your marketing materials is like saying your food is “biodynamic”. It sounds good…but what does that mean.]

Second, Specialty Providers: I'll start by saying I've spent my entire career in orthopedics and have seen some AMAZING surgeries and outcomes. Working at one of the best orthopedic hospital in the country showed me these ortho surgeons make a boatload of money. and some truly deserve it. However, I believe that in VBC, someone (a nursing home, a provider, an organization) has to lose money somewhere along the chain if you are really going to cut costs and improve outcomes. Specialty care accounts for 60% of total healthcare costs and the majority of spending for Medicare beneficiaries. If value-based care will ever work, we must figure out how to integrate specialty and primary care. Now I would like to add that not all surgeons fit this category. I worked with many incredible, innovative, forward-thinking ortho surgeons who wanted to change the system.

Third, Attribution... How do you attribute costs and spend fairly? I've worked with groups like Accorded and other actuaries in the past, and when you try to create solo conservative care episodes (i.e., Musculoskeletal care), attributing savings to a specialty care conservative episode becomes a highly complex exercise. Especially when multiple other episodes of care occur at the same time, with an ACO on top of it all, everyone wants some of that pie, but there's not enough pie to go around, or you try carving that pie with a stuffed animal rather than a knife.

[NK note: Has anyone ever heard or used this phrase before? What]

Fourth, transparency and quality.....Almost all quality measures are process or cost measures. i.e., how many MRIs did I do, or how many referrals did I send? I believe the accurate measure of quality is Patient-Reported Outcome measures. Understanding from the patient's point of view on how they feel is the only accurate subjective metric of whether this works or not (obviously, there are objective metrics like "Is all my cancer gone?"). However, standardizing and collecting PROMs is a massive administrative burden that increases costs and challenges even the most sophisticated organizations. There is no way to know who provides value from an outcome perspective, so it's challenging from a consumer end to say oh, this person is the best. I've had so many patients with meniscus or ACL tears who probably didn't need to be operated on because all they wanted to do was walk or go up and down stairs at their apartment. My 60-year-old patient, who has never played professional football nor will, maybe didn't need that ACL reconstruction because all he wanted to do was walk his daughter down the aisle.

Fifth, point solution fatigue ....apps for all! If I ever created a startup, I'd want to make one app that contained every health app you downloaded for all your conditions. You have chronic heart failure, oh great-we partnered with this VBC cardiac company to manage your symptoms, you also have diabetes - well there's this great RPM app to monitor A1C, oh you have a knee injury, check out this great VBC orthopedic app. Good luck remembering all your logins and passwords.

[NK note: “I’m going to start ONE point solution to combine all 15 other point solutions” - Person starting the 16th point solution.]

Lastly, here are my two cents on why this is good. During my time at an orthopedic hospital, we created excellent innovative programs that lower costs and improve outcomes. These programs had no FFS coding, so without BPCI, we wouldn't have been able to implement them. BPCI required hospitals to participate in the total hip and knee replacement bundle. With that, we implemented risk stratification, telehealth (in 2018, before it was cool), and other care coordination programs that kept the patients inside the four walls of our institution, literally and figuratively. We could better follow patient progress, ensure they were doing the right things in their home, and triage them back to us rather than being admitted to a community hospital when it was unnecessary. It can work! However, BPCI was a straightforward episode to implement from a payer and provider end.

Nothing I said in this email is mind-blowing or new. Most people in the space can relate to some or all of it. I have always been passionate about changing the healthcare system. Still, the more time I'm in it and the more time I learn the granular details, the less I feel that it can change without some radical intervention like Medicare for all (which I also do not think is the right way to go but will cause some sweeping changes).”

[NK note: I think this is the exact case that value-based care is good for de novo clinics/programs that can build natively to it. I think the fact that you see useful technology implementations that benefit both the patient and doctor without needing to wait for a CPT code to be created is a good indicator.

Starting to think this newsletter has become “therapy for value-based care people that have no one else to talk to”.]

—

Europe actually does have fee-for-service in a positive way

“A couple of stray thoughts from OOP's EU division.

1. I think Maryland's All-Payer Model is an interesting example to bring up because All-Payer Rate Setting is the norm in other "good healthcare" countries in the world and it's compatible with socialized medicine schemes like France and Japan as well as more market oriented schemes like Switzerland and Germany. Turns out you can save a lot of money by just setting prices and to a certain extent, providers will make rational decisions so they can stay within the budget.

2. French healthcare is Fee For Service driven to an extent that I would not have imagined. They're starting to mess around with some incentive payments for things-- there's a cool program that's trying to do more medication management in community pharmacies, etc.

There's obviously too many confounding factors to tell a neat story about why their outcomes are so much better in what is an extremely FFS scheme, but I've never let facts get in the way of a neat story, so...

Despite being "socialized medicine" in the sense that everything is paid for by the damn government, French care providers are, by and large, extremely entrepreneurial. There are very few medical groups, zero chain pharmacies, etc etc etc. I'd argue that healthcare is much more consumer driven here than the US. It's trivially easy to switch doctors when the network is every doctor in the country and they all cost the same, so doctors have to compete on perceived quality and service. (Of course, perceived quality and "good" service looks different to me than to a French person and don't get me started about trying to do a round of IVF in August here.)

But going on 2 years living here, I've become increasingly convinced that the US healthcare system would be much better served by more independent doctor-entrepreneurs from a cost, quality, and service perspective-- even without all the complexity of value-based care contracts.”

-Martin Cech

[NK note: Wait we have an EU division? Should I have been expensing all my italy trips?

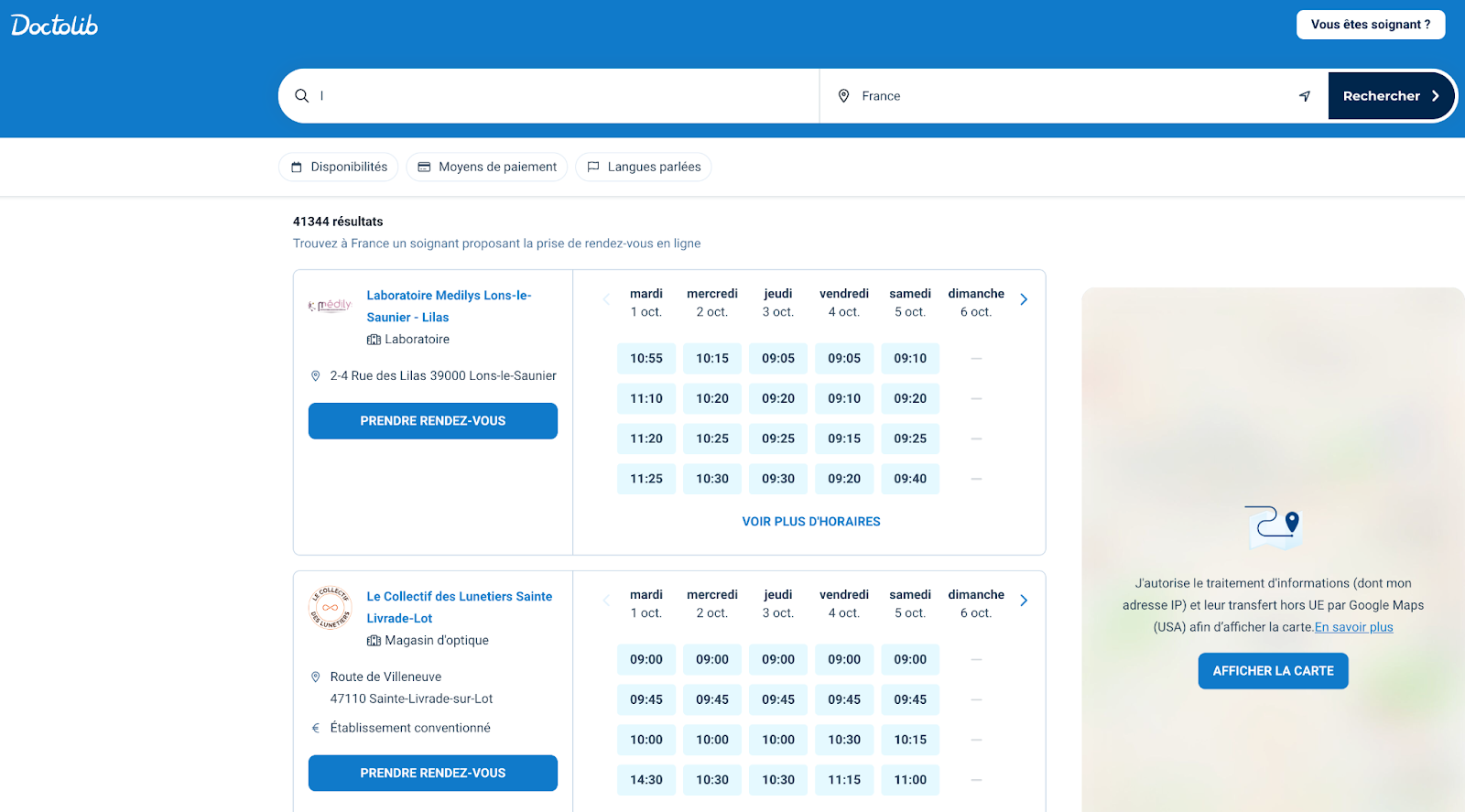

One thing I’ve been told is scheduling/practice management systems like Doctolib have been gamechangers for the rise of small practices. Combine that with a system where pricing is relatively set so you can’t charge much more just for being larger, and it makes sense why the playing field is more level for new practices.]

–

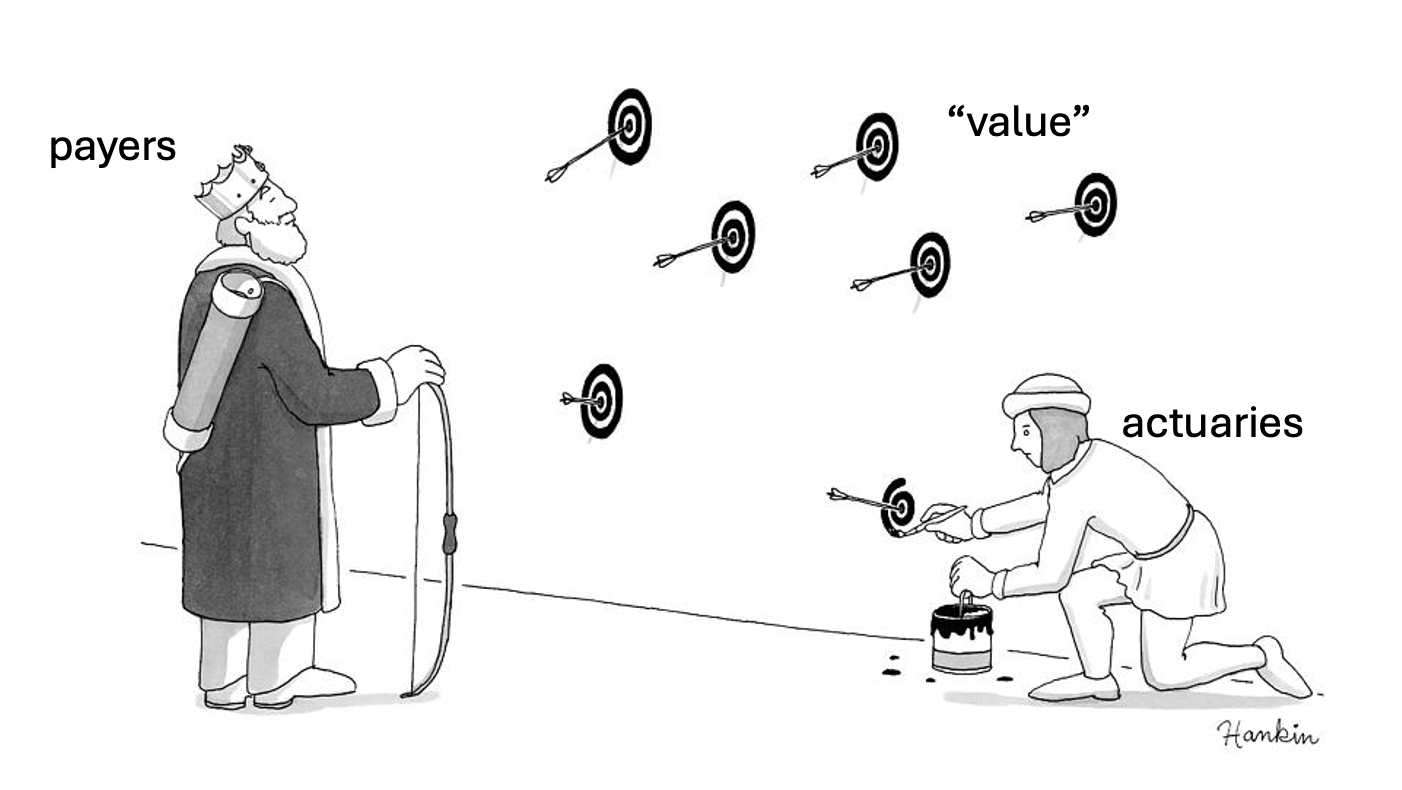

Actuaries have entered the chat - what’s “value”?

“Value-based care is unsuccessful for 2 main reasons:

1) "Value" is ill-defined, if at all. Ever hear the mantra "you can't manage what you can't measure"?

2) Trying to measure "value" is therefore impossible, but no one admits this. Once the fancy math reveals how money moves in a given program, focusing on that becomes the game.

As an actuary, we value the logical, formulaic nature of many things. However, most of what actuarial mathematics is designed to do is estimate probability and provide context to decisions with uncertain outcomes. Just because you slap a formula around something and say "we normalized for risk", it does not make it true in reality. Just like the multi-verse, there are tons of "value" formula outcomes that are entirely realistic but also completely random. Tons of resources are being dumped into tracking randomness around whichever levers drive the flow of funds.

It's funny how many people like to talk about SDoH and the studies that suggest 80%+ of quality/length of life are ACTUALLY dictated by factors outside of the Healthcare system. But population health is not the same as "my population" health. No one wants to truly invest in food, housing, education, and healthy habit formation when these things take lots of time and resources with no immediate return to the "investor". These things are not the responsibility of clinicians or insurers - it reasonably lies with the government or simply on the individuals themselves. Individuals are bad at long term risk/reward tradeoffs, and the government is bad at basically everything. The cycle continues.”

[NK Note: Hospitals have massive influence in local politics as the largest employer in many areas. An interesting question is whether they’d use their political sway to change some of these community level environmental factors. We had an interesting podcast episode with Andy Slavitt about the lead pipes in Flint and how no singular entity had the authority or money to make the changes to the pipes. So even within “the government should fix it”, the question is which part of the government?

A theoretically benefit of value-based care is that there is, in fact, a point person. Maybe with enough dollars at risk in a geography, the hospital would become that point person for larger, more community level fixes]

—

Do primary care physicians want to be gatekeepers?

“Implementation Challenges:

I have seen VBC applied to primary care where the PCP is given incentives to reduce costs for a population. They are asked to manage the patient, but there is much they don't control, like patient behavior when they tell them to lose weight or layoff the donuts and then there is the other stuff they can't control which are patients with chronic disease who need to see the

cardiologist, or get their hip replaced, or get dialysis (chronic disease where most of the money gets spent).

The patients are sick (at a population level) as we don't focus enough on prevention, so how does the PCP practice VBC here exactly? Is she somehow responsible for gatekeeping who see the cardiologist, what meds they take, what guideline based steps the patient must take before they get access to a therapy. The PCPs I know, want nothing to do with this. They want to take care of patients, give them the care they need and focus on medicine, not gatekeeping. I think this is one of the main reasons you don't see PCP jumping up and down for VBC programs.

[NK note: This is one of the things I hear a lot - that primary care clinicians are actually not the right people to figure out whether a patient needs downstream specialist care. And also that primary care clinicians don’t WANT to need to think about cost.]

I believe to be successful with VBC you must have all of the care elements under your roof, so you can control how services get used, and control the way they are used. Americans hate this kind of thing because it is a limited network and they don't always get the choices they want. Let's see how this plays out in the Medicare aged population. If you join an MA plan, you may pay less upfront if you are healthy, but if something goes wrong you have to deal with delay or denial and prior auth and then you get hit with big co-pays. If you go on straight Medicare, you pay more and probably have a supplemental, but once you clear your deductible, you basically get what you want approved, can see any doctor you want, and it's all paid for.

I think more people are beginning to understand this, and you already see many of the older folks moving back to straight Medicare especially as chronic diseases start to appear and fester. I wonder given the obvious incentives for patients to do this, whether MA hopes for these very expensive patients to be thrown over the wall to straight Medicare at the appropriate moment, much as private insurance just has to keep patients healthy until they jump to Medicare age.

What is probably required for a real VBC success:

I have thought about this a lot. To make this work I think you must eliminate all of the loopholes that create the wrong incentives. For example, you need to eliminate the loophole that private insurance can optimize for 0-65 before handing their problems to Medicare. I think you

need to remove capitation as currently imagined where an MA plan essentially estimates (guesses) what a patient will require for spend when they have actually little control over what the patients care journey will be (other than delay or denial). And you need to remove much of the administrative burden that all this produces. If we want VBC then the right answer is a single payer universal system, and one that starts at birth and goes until death. No longer should there be an arbitrary dividing line at 65.

Capitation is decided at the highest level of the system (by the countries budget). Insurance coverage, eligibility, co-pays, etc etc are now a given. Care decisions, guidelines, prior auth all of those things may still happen, but they will be one set of rules that can be standardized. Payments and reimbursements will still be a headache, and there are legitimate regional

differences that have to be accounted for. But insurance companies and provider systems won't spend gobs of time and money negotiating with 15 different plans every year.

Will it all be better? There will be compromises without a doubt, the patients will have less control over their journeys and fewer choices. PCPs (but specialists also), may have to engage in gatekeeping, but at least it will be a level playing field. Since the whole system will now be ultimately capitated by the overall budget, there is intrinsic VBC. As budgets stay flat, decline or rise slowly there will be room for people to find better ways to spend the money and better answer for how to care for patients. It will be messy, but it will be better than the chaotic system we have now. Of course, this is nothing but a dream. To imagine the country could agree and implement such a dramatic change is unfathomable.

So, to simplify, implementing VBC in a multipayer system is probably a fool's errand. It might make some changes on the margins, but it’s not going to create the revolution. We can have pockets of VBC, say the VA for example, or specific disease states i.e. kidney care or bundled payments for knee replacements, these can work. I think it makes sense to have that be the ambition. Going beyond that to manage populations, or do primary care does not seem viable.”

[NK note: This sounds like a variation of what Germany’s healthcare system looks like. Health insurance companies are essentially regulated as utilities and there’s some small variation at the edges. In the US the health insurance companies have the innovation levels of utilities but without the benefits of standardization across them.]

–

Some criteria for good value-based care areas (potentially)

“First off, value should account for both outcomes and price, Value = Outcomes/Dollar. People seem to confuse 'value based' with 'reducing cost'. If you improve outcomes, that should be considered successful VBC.

Second, There is an ideal population for Value based care. imo it should be a longitudinal episode/population, high risk, easily identifiable and there should be the ability to transfer risk onto one entity.

- Longitudinal: Follow patients for longer periods of time to allow savings to accrue.

- High risk: biggest ability to reduce spend.

- Easy ID of patients and outcomes: Makes administering easier. Patients who are at risk of 'using unnecessary services' should be identifiable (often requires some disease specific knowledge).

- One entity with full risk: I feel like having 82 people in the risk stack makes administering VBC hard. One provider should take all the risk and every other entity should participate in a shared savings type model where they are paid based on achieving set goals.

Third, We have a lot of issues with the current models. The promise of VBS is aligning incentives so 'more care' doesn't lead to more profits. Thus people are incentivized to provide the best care. But if you look at the models, there are 4 ways to make a profit in VBC:

1) reduce provision of care

2) risk adjust up

3) shift financial burden (similar to your 'what goes in must come out' idea, look up how insurers use whitebagging to shift costs from part B to part D)

4) improve outcomes

4 is the goal. but 1-3 are easiest. So how can you implement VBC without having united health deny you care after chasing you down for an HIV diagnosis?

Anchor to historical data to craft an initial payment fee. Set a price per patient. Allow the risk bearing entities to capture any upside on improving outcomes but not upside on risk adjustment.

[NK note: “anchor to historical data” sounds easy in theory but hard in practice. Do you anchor to each individual provider and their own spend? The average provider in that geography?]

I'm a big believer in VBC, specifically in Oncology because I think it fits a lot of these characteristics. High risk, longitudinal, etc. The OCM was seen as a mediocre model but imo it worked quite well. Costs were reduced, but the performance payments layered on top led to net losses. Why not pay the original price and allow upside capture?

This may not be sustainable long term because eventually we run out of ideas to improve outcomes, but let me know when we perfect healthcare.

I also do think VBC favors large entities, because of willingness to take risk and suffer some losses. This isn't necessarily bad if you structure it right imo (see Kaiser, everyone loves them)

"Everybody wants Value based Care, Nobody wants to take on full risk””

[NK note: One thing alluded to is that we need to find appropriate levers to reduce spend. There are certain disease areas where we know that it’ll be high cost but there’s not a ton we can do about it e.g. many neurodegenerative disorders. This is an area in particular we should be attempting more moonshots on the drug/device side IMO.]

The secret to VBC success is…fraud

“Value based care has always had a great narrative, but I have rarely seen it work in practice. Most recently, it’s been a really effective way to defraud the medicare HI and SMI funds via risk adjustment. Most of those who have been successful in value based care focus almost all of their efforts in risk adjustment coding, a complicated system where it’s been really difficult for anyone to prove fraud. Because it’s not zero sum, it’s been a great way to line the pockets of those in the VBC space, just with extra steps and muddying up waters in court. If I hear “documenting illness burden accurately” one more time… v28 has been a help, but not enough to put a nail in the coffin for MA RA.

Risk has also been a big part of ACO REACH. Take a look at the change in normalization factor between 2021 and 2023 for A&D prospective. Did patients just magically get 12% sicker from a reference population over night? [insert surprised pikachu]

KFF sues for RADV under FOIA in 2019, CMS kicks and screams for 3 years. CMS shows finally shows RADV for MA between 2011 - 2013. Good to know if you commit fraud, you won’t be held accountable for 7-10 years + appeals time. Also, no extrapolation until 2018? How is not someone in jail? It’s only like $200 fucking billion over 10 years.

Stepping away from risk adjustment; let’s also take a look at CMMI. 10 years and 49 models running. I think only 1-2 only showed material successes. Missed the mark by $8.2 billion these past 10 years, and increased taxpayer spending. And going to miss the mark by another $78.8 billion over the next 10 years. Oof. Thank god for PAYGO. I think if you randomly select 150 value based care models, you will find 5-6 successful ones over shorter periods of time, but that’s just due to random noise IMO or forces beyond control of the VBC attempt. There’s just things that are beyond your control or forces you’re not even aware of. For example, in your ACO REACH related figures in this article, savings figures and policy changes called out can be explained by one weird thing. Hint: it has to do with fish. Second example: CMS-1799-F.

I think value based care has been successful because it has a really good story that goes along with it, but the implementation is a breeding ground for complexity, which can then be a breeding ground for fraud or responding to incentives in unexpected and creative ways. It’s also one of those things that is hard to undo because of how many jobs are now tied up in it as well. Also touching seniors medicare benefit in any way is political suicide. Axing value based care is likely impossible, but people are gonna sell shovels until there’s no more gold left.”

-Anonymous

[NK note: this is so in the weeds of value-based care that even I can’t follow like 75% of it. But if you’re reading this far into the post then you must really be into value-based care, so I figured you might learn something from this anon’s rant.

One thing that I can understand though is that companies that were involved in egregious upcoding can get away with bilking taxpayers out of a lot of money without any individuals seeing personal liability. This does feel like a failing, but it’s a longer conversation about corporate responsibility and liability.]

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “Value-Based Confession Booth”

Twitter: @nikillinit

IG: @outofpockethealth

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

--

{{sub-form}}

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!!

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

Selling to Health Systems (starts 10/6) - Hopefully this post explained the perils of selling point solutions to hospitals. We’ll teach you how to sell to hospitals the right way.

EHR Data 101 (starts 10/14) - Hands on, practical introduction to working with data from electronic health record (EHR) systems, analyzing it, speaking caringly to it, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →Our Healthcare 101 Learning Summit is in NY 1/29 - 1/30. If you or your team needs to get up to speed on healthcare quickly, you should come to this. We'll teach you everything you need to know about the different players in healthcare, how they make money, rules they need to abide by, etc.

Sign up closes on 1/21!!!

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.